Home – The Conversation |

- Abortion benefits: Companies have a simple and legal way to help their workers living in anti-abortion states – expanding paid time off

- Viruses can change your scent to make you more attractive to mosquitoes, new research in mice finds

- Winning the Tour de France requires subtle physics, young muscles and an obscene amount of calories – 3 essential reads

- Kremlin tightens control over Russians' online lives – threatening domestic freedoms and the global internet

- When does the fetus acquire a moral status of a human being? The philosophy of 'gradualism' can provide answers

- Tour de France: How many calories will the winner burn?

- People vary a lot in how well they recognize, match or categorize the things they see – researchers attribute this skill to an ability they call 'o'

- A water strategy for the parched West: Have cities pay farmers to install more efficient irrigation systems

- More states will now limit abortion, but they have long used laws to govern – and sometimes jail – pregnant women

- The Supreme Court has overturned precedent dozens of times, including striking down legal segregation and reversing Roe

- Racial wealth gaps are yet another thing the US and UK have in common

- Jan. 6 hearings highlight problems with certification of presidential elections and potential ways to fix them

| Posted: 30 Jun 2022 11:18 AM PDT  Employers looking for ways to support their workers seeking abortions in states where it's now illegal or soon will be don't have it easy. From an employer's standpoint, abortion is considered a type of health care benefit – and the rules that apply to that benefit are shifting rapidly from state to state. Abortion is also a political flashpoint guaranteed to produce controversy. And the problem is not going away anytime soon. Some companies are vowing to cover the cost of traveling out of state to get the procedure where it is still legal. Others are emphasizing that their insurance plans explicitly cover abortions. As a legal scholar specializing in employment law, I believe there's also a third option that may not be as generous but is less likely to run into legal problems – and will help more workers, especially those with low incomes. Covering medical costs directlyAs of 2020, the median cost of an abortion was US$500 to $600 in the first trimester, and around $900 in the second trimester. Although most women seeking an abortion pay for the procedure out of pocket, some companies cover abortion in their health plans. In a recent statement, for example, Uber touted that its employee health plan includes abortion costs. And employers in a handful of states such as California and New York are required to include abortion in any health plan they offer. However, other states outlaw health coverage for abortion under state insurance laws. Even before the recent Supreme Court abortion decision, 11 states including North Dakota and Texas had already prohibited or limited private insurance from paying for the procedure. Companies that fund their own health benefit plan may be in a better position to avoid restrictions in state insurance laws. But switching to a self-funded plan is unaffordable for most small or medium-sized businesses. And self-funding may not protect companies if states decide to criminalize abortion. In other words, companies do not have a lot of room to maneuver when it comes to covering abortions in states that are determined to prohibit the procedure.  The travel expense optionMicrosoft, Citigroup and at least 50 other U.S. companies have pledged in recent weeks to reimburse workers for travel expenses associated with out-of-state medical care, including abortion. Kroger and Dick's Sporting Goods, for example, offered employees up to $4,000 to cover such expenses, while Zillow said it would reimburse up to $7,500 when travel is required for abortion or certain other medical procedures. Nevertheless, I suspect many companies may shy away from adopting similar policies. A survey in early June found that only 14% of companies already had a policy in place to reimburse abortion-related travel expenses, while another 25% said they were considering it. Although those numbers could grow, leading law firms have cautioned that such policies could create legal risks similar to those involved in covering health care costs. Anti-abortion states could even directly prohibit travel reimbursement for out-of-state abortions. Texas lawmakers, for example, are already threatening to pass a law that would "bar companies from doing business in Texas if they pay for residents of the state to receive abortions elsewhere." And while there are reasons to believe interstate travel would be constitutionally protected, any ensuing litigation would take years to resolve. As a result, many companies may simply decide against offering abortion travel benefits to workers in states where the procedure is banned.  A simpler solution that helps everyoneThis doesn't mean that companies are completely powerless to help workers in an anti-abortion state. Workers who need to drive hundreds of miles for care unavailable in their state will – at a minimum – need time off work. And while most workers have some access to paid leave, those benefits are predominantly available to high-wage earners. By contrast, roughly half of workers on the low end of the wage scale lack paid sick leave or vacation time. These workers are left in an impossible position if they need to travel for an abortion. They generally aren't even entitled to unpaid time off, unless they are covered by the Family and Medical Leave Act and their condition qualifies as a "serious health condition." Instead, they are left to cajole co-workers to cover their shifts and hope managers cut them a break. And every hour a worker without vacation or sick leave spends driving to another state for medical care is an hour they aren't being paid. An employee making $15 an hour who loses a week of work for an out-of-state abortion stands to forgo as much money as the cost of the procedure itself. In other words, the workers who can least afford to forgo wages for an abortion are most likely to be put in that position. If companies are reluctant or unable to pay for travel expenses – or the procedure itself – they can at least pay workers for the time they are away from work. Expanding sick leave and vacation leave to a broader swath of workers may also avoid some of the pitfalls of other corporate interventions. Even if state legislatures pass draconian laws such as the Texas law that prohibits "aiding and abetting," companies rarely know exactly how workers spend their time off – particularly when it comes to vacation time. It's harder then to pin liability on the employer. More privacy, less controversyFor the same reason, sick leave and vacation policies also provide workers with a measure of privacy. Unlike policies involving travel or health benefits, employees can often avail themselves of time off without providing receipts or documentation. Finally, a quiet expansion of the company's paid time off enables employers to help women without attracting controversy. Companies are already nervous about abortion-related discussions at work. They may not want to generate more internal conflict at a time when partisan rancor is at a fever pitch. And while expanding paid time off may not seem like a lot, it would be one less hurdle for women experiencing nothing but hurdles. Elizabeth C. Tippett does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |

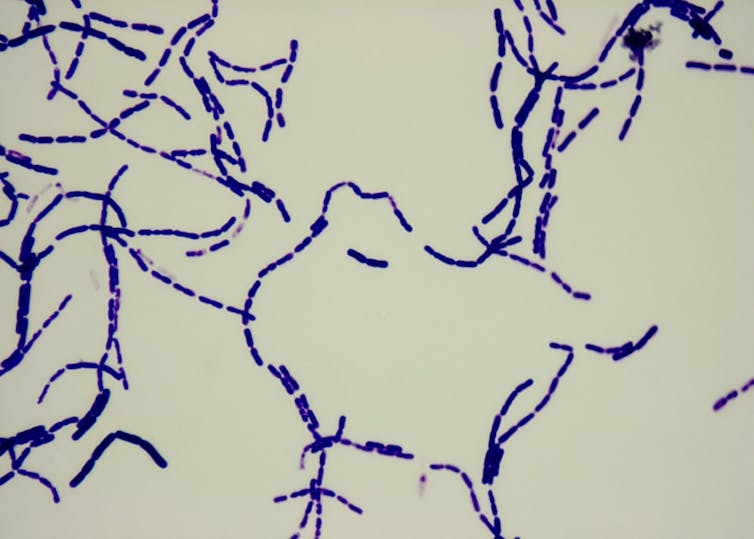

| Viruses can change your scent to make you more attractive to mosquitoes, new research in mice finds Posted: 30 Jun 2022 08:20 AM PDT  Mosquitoes are the world's deadliest animal. Over 1 million deaths per year are attributed to mosquito-borne diseases, including malaria, yellow fever, dengue fever, Zika and chikungunya fever. How mosquitoes seek out and feed on their hosts are important factors in how a virus circulates in nature. Mosquitoes spread diseases by acting as carriers of viruses and other pathogens: A mosquito that bites a person infected with a virus can acquire the virus and pass it on to the next person it bites. For immunologists and infectious disease researchers like me, a better understanding of how a virus interacts with a host may offer new strategies for preventing and treating mosquito-borne diseases. In our recently published study, my colleagues and I found that some viruses can alter a person's body odor to be more attractive to mosquitoes, leading to more bites that allow a virus to spread. Viruses change host odors to attract mosquitoesMosquitoes locate a potential host through different sensory cues, such as your body temperature and the carbon dioxide emitted from your breath. Odors also play a role. Previous lab research has found that mice infected with malaria have changes in their scents that make them more attractive to mosquitoes. With this in mind, my colleagues and I wondered if other mosquito-borne viruses, such as dengue and Zika, can also change a person's scent to make them more attractive to mosquitoes, and whether there is a way to prevent these changes. To investigate this, we placed mice infected with the dengue or Zika virus, uninfected mice and mosquitoes in one of three arms of a glass chamber. When we applied airflow through the mouse chambers to funnel their odors toward the mosquitoes, we found that more mosquitoes chose to fly toward the infected mice over the uninfected mice. We ruled out carbon dioxide as a reason for why the mosquitoes were attracted to the infected mice, because while Zika-infected mice emitted less carbon dioxide than uninfected mice, dengue-infected mice did not change emission levels. Likewise, we ruled out body temperature as a potential attractive factor when mosquitoes did not differentiate between mice with elevated or normal body temperatures. Then we assessed the role of body odors in the mosquitoes' increased attraction to infected mice. After placing a filter in the glass chambers to prevent mice odors from reaching the mosquitoes, we found that the number of mosquitoes flying toward infected and uninfected mice were comparable. This suggests that there was something about the odors of the infected mice that drew the mosquitoes toward them.  To identify the odor, we isolated 20 different gaseous chemical compounds from the scent emitted by the infected mice. Of these, we found three to stimulate a significant response in mosquito antennae. When we applied these three compounds to the skin of healthy mice and the hands of human volunteers, only one, acetophenone, attracted more mosquitoes compared to the control. We found that infected mice produced 10 times more acetophenone than uninfected mice. Similarly, we found that the odors collected from the armpits of dengue fever patients contained more acetophenone than those from healthy people. When we applied the dengue fever patient odors on one hand of a volunteer and a healthy person's odor on the other hand, mosquitoes were consistently more attracted to the hand with dengue fever odors. These findings imply that the dengue and Zika viruses are capable of increasing the amount of acetophenone their hosts produce and emit, making them even more attractive to mosquitoes. When uninfected mosquitoes bite these attractive hosts, they may go on to bite other people and spread the virus even further. How viruses increase acetophenone productionNext, we wanted to figure out how viruses were increasing the amount of mosquito-attracting acetophenone their hosts produce. Acetophenone, along with being a chemical commonly used as a fragrance in perfumes, is also a metabolic byproduct commonly produced by certain bacteria living on the skin and in the intestines of both people and mice. So we wondered if it had something to do with changes in the type of bacteria on the skin. To test this idea, we removed either the skin or intestinal bacteria from infected mice before exposing them to mosquitoes. While mosquitoes were still more attracted to infected mice with depleted intestinal bacteria compared to uninfected mice, they were significantly less attracted to infected mice with depleted skin bacteria. These results suggest that skin microbes are an essential source of acetophenone.  When we compared the skin bacteria compositions of infected and uninfected mice, we identified that a common type of rod-shaped bacteria, Bacillus, was a major acetophenone producer and had significantly increased numbers on infected mice. This meant that the dengue and Zika viruses were able to change their host's odor by altering the microbiome of the skin. Reducing mosquito-attracting odorsFinally, we wondered if there was a way to prevent this change in odors. We found one potential option when we observed that infected mice had decreased levels of an important microbe-fighting molecule produced by skin cells, called RELMα. This suggested that the dengue and Zika viruses suppressed production of this molecule, making the mice more vulnerable to infection. Vitamin A and its related chemical compounds are known to strongly boost production of RELMα. So we fed a vitamin A derivative to infected mice over the course of a few days and measured the amount of RELMα and Bacillus bacteria present on their skin, then exposed them to mosquitoes. We found that infected mice treated with the vitamin A derivative were able to restore their RELMα levels back to those of uninfected mice, as well as reduce the amount of Bacillus bacteria on their skin. Mosquitoes were also no more attracted to these treated, infected mice than uninfected mice. Our next step is to replicate these results in people and eventually apply what we learn to patients. Vitamin A deficiency is common in developing countries. This is especially the case in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, where mosquito-transmitted viral diseases are prevalent. Our next steps are to investigate whether dietary vitamin A or its derivatives could reduce mosquito attraction to people infected with Zika and dengue, and subsequently reduce mosquito-borne diseases in the long term. Penghua Wang receives funding from the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, United States organization. He is a regular member of American Association of Immunologists, American Society for Virology, The Society of Chinese Bioscientists in America. |

| Posted: 30 Jun 2022 07:25 AM PDT  The 2022 Tour de France is here. Starting in Copenhagen on July 1, the tour covers almost 2,100 miles (3,380 kilometers) over 24 days of riding through Denmark, Belgium, Switzerland and France. The tour is a feat of human athleticism, but to really understand how incredible it is to complete the race – much less win it – requires thinking about a unique blend of physics, biology and physiology. Mix those up just right and you get a Tour de France champion. Over the years, The Conversation has published a series of stories covering the science of the Tour de France and elite athletics. Below are excerpts from three of those stories to help you better appreciate this spectacular race.  1. The biomechanics of riding a bikeRiding a bike is an easy thing to do once you learn, but the physics of how bikes and riders work together is surprisingly complicated. As Stephen Cain, a mechanical engineer at West Virginia University, explains, "A big part of balancing a bicycle has to do with controlling the center of mass of the rider-bicycle system." Basically, you have to keep the center of mass above the wheels – otherwise you tip over. "Bicycle riders can use two main balancing strategies: steering and body movement relative to the bike," says Cain. Steering keeps the bike underneath you while body movements subtly shift your center of gravity. Cain and his colleagues ran a study to understand the difference between how novice and professional cyclists balance a bike, and as he says in his article, they found that "both novice and expert riders exhibit similar balance performance at slow speeds. But at higher speeds, expert riders achieve superior balance performance by employing smaller but more effective body movements and less steering." This fine-scale control is why the racers in the Tour de France barely look like they are steering at all. Read more: The mysterious biomechanics of riding – and balancing – a bicycle 2. How many calories do Tour riders burn?Think back to the last time you did some hard exercise and how hungry you were that evening. Now imagine how hungry you would be if you needed to ride your bike over 100 miles (165 km) and climb nearly 10,000 feet (about 3,050 meters) of elevation in less than five hours. This is what racers will have to do during Stage 12 of this year's race as they traverse mountain passes through the French Alps. As Eric Goff, a sports physicist at the University of Lynchburg explains, the cyclists are going to need a lot of fuel to pull this off.  "To make a bicycle move, a Tour de France rider transfers energy from his muscles, through the bicycle and to the wheels that push back on the ground," says Goff. Professional cyclists are in another league when it comes to producing power with their legs, but they are still limited by basic human biology. "Muscles, like any machine, can't convert 100% of food energy directly into energy output," explains Goff. "Muscles can be anywhere between 2% efficient when used for activities like swimming and 40% efficient in the heart." With mountains to climb and glory to claim, riders need to fuel their muscles with food. In his story, Goff calculates that over the course of the Tour de France, racers will burn an astonishing 120,000 colories – the equivalent of about 210 Big Macs. Read more: Tour de France: How many calories will the winner burn? 3. Biology explains why professional athletes are youngWhen you watch the Tour de France, soccer's World Cup or the Olympics, it's common to see a young teenage phenom, but it's rare for anyone over the age of 40 to be competing. Roger Fielding, an aging and exercise researcher at Tufts University, writes that "old and young people build muscle in the same way." But there is a biological reason no 50-year-old has ever won the Tour de France: "As you age, many of the biological processes that turn exercise into muscle become less effective." Muscles grow thanks to a number of complicated cellular pathways that are activated during exercise. When this network of receptors and signaling chemicals gets triggered, the body responds by increasing muscle size – and even makes some small tweaks to what genes are active. But as Fielding explains, in older people "the signal telling muscles to grow is much weaker for a given amount of exercise. These changes begin to occur when a person reaches around 50 years old and become more pronounced as time goes on." Many people can and do get into the best shape of their lives when they are in their 50s or 60s. But the fact that it is harder to get fit as you age is a major reason why it's so important for older people to exercise – and why you won't see any retirees leading the peloton in the Tour de France. |

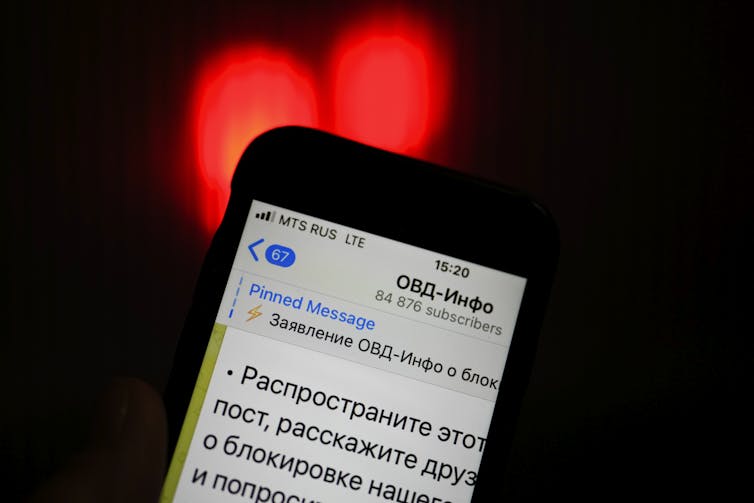

| Posted: 30 Jun 2022 05:31 AM PDT  Since the start of Russia's war on Ukraine in late February 2022, Russian internet users have experienced what has been dubbed the descent of a "digital iron curtain." Russian authorities blocked access to all major opposition news sites, as well as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. Under the new draconian laws purporting to combat fake news about the Russian-Ukrainian war, internet users have faced administrative and criminal charges for allegedly spreading online disinformation about Russia's actions in Ukraine. Most Western technology companies, from Airbnb to Apple, have stopped or limited their Russian operations as part of the broader corporate exodus from the country. Many Russians downloaded virtual private network software to try to access blocked sites and services in the first weeks of the war. By late April, 23% of Russian internet users reported using VPNs with varying regularity. The state media watchdog, Roskomnadzor, has been blocking VPNs to prevent people from bypassing government censorship and stepped up its efforts in June 2022. Although the speed and scale of the wartime internet crackdown are unprecedented, its legal, technical and rhetorical foundations were put in place during the preceding decade under the banner of digital sovereignty. Digital sovereignty for nations is the exercise of state power within national borders over digital processes like the flow of online data and content, surveillance and privacy, and the production of digital technologies. Under authoritarian regimes like today's Russia, digital sovereignty often serves as a veil for stymieing domestic dissent. Digital sovereignty pioneerRussia has advocated upholding state sovereignty over information and telecommunications since the early 1990s. In the aftermath of the Cold War, a weakened Russia could no longer compete with the U.S. economically, technologically or militarily. Instead, Russian leaders sought to curtail the emergent U.S. global dominance and hold on to Russia's great power status. They did so by promoting the preeminence of state sovereignty as a foundational principle of international order. In the 2000s, seeking to project its great power resurgence, Moscow joined forces with Beijing to spearhead the global movement for internet sovereignty. Despite its decades-long advocacy of digital sovereignty on the world stage, the Kremlin didn't begin enforcing state power over its domestic cyberspace until the early 2010s. From late 2011 to mid-2012, Russia saw the largest series of anti-government rallies in its post-Soviet history to protest Vladimir Putin's third presidential run and fraudulent parliamentary elections. As in the anti-authoritarian uprisings in the Middle East known as the Arab Spring, the internet served as a critical instrument in organizing and coordinating the Russian protests. Following Putin's return to the presidency in March 2012, the Kremlin turned its attention to controlling Russian cyberspace. The so-called Blacklist Law established a framework for blocking websites under the guise of fighting child pornography, suicide, extremism and other widely acknowledged societal ills. However, the law has been regularly used to ban sites of opposition activists and media. The law widely known as the Blogger's Law then subjected all websites and social media accounts with over 3,000 daily users to traditional media regulations by requiring them to register with the state.  The next pivotal moment in Moscow's embrace of authoritarian digital sovereignty came after Russia's invasion of eastern Ukraine in the Spring of 2014. Over the following five years, as Russia's relations with the West worsened, the Russian government undertook a barrage of initiatives meant to tighten its control over the country's increasingly networked public. The data localization law, for example, required foreign technology companies to keep Russian citizens' data on servers located within the country and thus easily accessible to the authorities. Under the pretext of fighting terrorism, another law required telecom and internet companies to retain users' communications for six months and their metadata for three years and hand them over to authorities upon request without a court order. The Kremlin has used these and other legal innovations to open criminal cases against thousands of internet users and jail hundreds for "liking" and sharing social media content critical of the government. The Sovereign Internet LawIn April 2019, Russian authorities took their aspirations for digital sovereignty to another level with the so-called Sovereign Internet Law. The law opened the door for abuse of individual users and isolation of the internet community as a whole. The law requires all internet service providers to install state-mandated devices "for counteracting threats to stability, security, and the functional integrity of the internet" within Russian borders. The Russian government has interpreted threats broadly, including social media content. For example, the authorities have repeatedly used this law to throttle the performance of Twitter on mobile devices when Twitter has failed to comply with government requests to remove "illegal" content. Further, the law establishes protocols for rerouting all internet traffic through Russian territory and for a single command center to manage that traffic. Ironically, the Moscow-based center that now controls traffic and fights foreign circumvention tools, such as the Tor browser, requires Chinese and U.S. hardware and software to function in the absence of their Russian equivalents. Lastly, the law promises to establish a Russian national Domain Name System. DNS is the global internet's core database that translates between web names such as theconversation.com and their internet addresses, in this case 151.101.2.133. DNS is operated by a California-based nonprofit, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers. At the time of the law's passing, Putin justified the national DNS by arguing that it would allow the Russian internet segment to function even if ICANN disconnected Russia from the global internet in an act of hostility. In practice, when, days into Russia's invasion in February 2022, Ukrainian authorities asked ICANN to disconnect Russia from the DNS, ICANN declined the request. ICANN officials said they wanted to avoid setting the precedent of disconnecting entire countries for political reasons. Splitting the global internetThe Russian-Ukrainian war has undermined the integrity of the global internet, both by Russia's actions and the actions of technology companies in the West. In an unprecedented move, social media platforms have blocked access to Russian state media. The internet is a global network of networks. Interoperability among these networks is the internet's foundational principle. The ideal of a single internet, of course, has always run up against the reality of the world's cultural and linguistic diversity: Unsurprisingly, most users don't clamor for content from faraway lands in unintelligible languages. Yet, politically motivated restrictions threaten to fragment the internet into increasingly disjointed networks. Though it may not be fought over on the battlefield, global interconnectivity has become one of the values at stake in the Russian-Ukrainian war. And as Russia has solidified its control over sections of eastern Ukraine, it has moved the digital Iron Curtain to those frontiers. Stanislav Budnitsky does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |

| Posted: 30 Jun 2022 05:27 AM PDT  I lost my twins in the second trimester of my first pregnancy. One fetus died around 14 weeks, and a month later I went into preterm labor – likely caused by the death of the first and an infection. I delivered the second twin, who appeared perfectly healthy on the ultrasound but was simply not old enough to survive, at 18½ weeks. I grieved for years; these were some of my worst moments. Ten years later, this experience is never far from my mind. But in the past few days since the U.S. Supreme Court's overturning of Roe v. Wade, it's also been a source of constant rumination. I think about the fact that the dilation and curettage, a common early abortion procedure I received to remove the placenta, is now banned when used to end a pregnancy involving a live fetus in almost all circumstances in six states. If my body had not ended the pregnancy, I wonder – would medical professionals have been too scared of prosecution to help me if the infection had worsened? But mostly, I think about what the Supreme Court ruling of June 24, 2022, will mean for abortion in the second trimester. With early abortion banned or heavily restricted in much of the country, there will likely be a rise in second-trimester abortions, as several commentators have pointed out. From my personal perspective, it is morally abhorrent to deny anyone the ability to access abortion in their own state, no matter why they are seeking one. But the likelihood of more abortions being pushed into the second trimester, as pregnant individuals must overcome more barriers to access, also matters from the point of view of moral concern about fetuses. Many people feel that losing a pregnancy after a few months is more tragic than an early loss. The same is true for later versus earlier abortion. As a moral philosopher, I know that the philosophical theory of gradualism can help make sense of this idea. Gradualism insists that the development of moral status is a gradual process that occurs continuously throughout gestation. That means that later fetuses have more status than earlier ones; later abortions too are more grave morally. Restrictions and delayed abortionsMost abortions in the U.S. tend to occur quite early: 79.3% at 9 weeks or earlier and 92.7% before 14 weeks. Compare that with 1974, just a year after the landmark decision in Roe v. Wade, when 21% of abortions took place in the second trimester. Some second-trimester abortions are pursued because of fetal anomalies that are not discovered until later; in other cases the pregnant individual might want or need to end the pregnancy because of changes in their health or life circumstances. Other factors leading to second-trimester abortions, however, are policy-based. Restrictions on public funding and mandated waiting periods can delay abortion care. Research shows that when states institute waiting periods of just 24 hours, the rate of second-trimester abortion increases for those relying on in-state providers. In 2015, Tennessee's new waiting period led to a 22% to 43% increase in the second-trimester abortion rate. Following the recent Supreme Court ruling, it is likely that delays will become the norm, since many pregnant individuals will have to travel hundreds of miles to the closest provider. Having seen surges of patients from Texas traveling to neighboring states, following the state's adoption of a law banning abortion, clinics in blue states are preparing for influxes of out-of-state patients. Providers have also witnessed the later gestational age at which abortion is obtained by those affected by Texas' ban. Thus, even if pregnant individuals from the South and Midwest can eventually access abortion in another state, they might be forced to continue the pregnancy for weeks or months. Second-trimester procedures have more health risks than earlier terminations, they are more financially burdensome and there are fewer providers trained to offer them. Moreover, both providers and patients can find second-trimester abortion morally and emotionally difficult. In fact, 91% of those having an abortion procedure in the second trimester would have preferred to do so earlier. What's the moral status of a fetus?The morality of abortion depends in part on the moral status of a fetus. Full moral status – sometimes called "personhood" – refers to having the same rights and deserving the same moral consideration as any other human being.  The most well-known views about the value of fetal life look for a specific moment or threshold of development at which a fetus achieves full moral status – what is known as a "bright line." Most opponents of abortion tend to insist that conception is the bright line, while some abortion-rights supporters look to birth or the first breath. In the Roe era, viability, the point at which a baby can survive outside of the womb, considered to be about 23 weeks, served as a legal bright line. Historically, "quickening," when the pregnant individual feels fetal movement, at around four months or so, was thought to make all the moral difference. In contrast to these bright lines, many philosophers look to cognitive capacities, such as consciousness, reasoning or self-awareness, which do not develop until the third trimester or even after birth. These views share in common the idea that before the bright line fetuses are of little to no moral concern. Gradualism rejects all of this. It holds that there is no such bright line. Instead, the development of moral status parallels the physical, cognitive and relational development of a fetus. Just after conception, a zygote has little more status than a sperm and egg. But as the embryo develops, its moral value increases slowly and steadily. Thus, while a 6- or 8-week embryo might have very minimal status, a fetus at 32 or 35 weeks has virtually identical moral status to a newborn. Therefore, the earliest abortion is generally morally unconcerning to someone with a gradualist view, while third-trimester abortion is seen as a grave action that requires the strongest of moral reasons. Meanwhile, midpregnancy fetuses are morally "in between," as gradualist philosopher Margaret Little puts it. The idea is that by this point in pregnancy fetuses have not achieved full moral status, but they certainly have significant moral value – and ending their lives therefore requires moral justification. Compared with the bright line views, gradualism has the benefit of making sense of the public's strong support for early abortion, but hesitating about terminations in the second and third trimesters. In the post-Roe era, the view also highlights the moral tragedy if state abortion bans targeting early abortion increase the number of second-trimester terminations. After all, from a gradualist view, early abortion is not seriously morally concerning, but second-trimester abortion is. Amanda Roth does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |

| Tour de France: How many calories will the winner burn? Posted: 30 Jun 2022 05:23 AM PDT   Imagine you begin pedaling from the start of Stage 12 of this year's Tour de France. Your very first task would be to bike approximately 20.6 miles (33.2 km) up to the peak of Col du Galibier in the French Alps while gaining around 4,281 feet (1,305 m) of elevation. But this is only the first of three big climbs in your day. Next you face the peak of Col de la Croix de Fer and then end the 102.6-mile (165.1-km) stage by taking on the famous Alpe d'Huez climb with its 21 serpentine turns. On the fittest day of my life, I might not even be able to finish Stage 12 – much less do it in anything remotely close to the five hours or so the winner will take to finish the ride. And Stage 12 is just one of 21 stages that must be completed in the 24 days of the tour. I am a sports physicist, and I've modeled the Tour de France for nearly two decades using terrain data – like what I described for Stage 12 – and the laws of physics. But I still cannot fathom the physical capabilities needed to complete the world's most famous bike race. Only an elite few humans are capable of completing a Tour de France stage in a time that's measured in hours instead of days. The reason they're able to do what the rest of us can only dream of is that these athletes can produce enormous amounts of power. Power is the rate at which cyclists burn energy and the energy they burn comes from the food they eat. And over the course of the Tour de France, the winning cyclist will burn the equivalent of roughly 210 Big Macs. Cycling is a game of wattsTo make a bicycle move, a Tour de France rider transfers energy from his muscles, through the bicycle and to the wheels that push back on the ground. The faster a rider can put out energy, the greater the power. This rate of energy transfer is often measured in watts. Tour de France cyclists are capable of generating enormous amounts of power for incredibly long periods of time compared to most people. For about 20 minutes, a fit recreational cyclist can consistently put out 250 watts to 300 watts. Tour de France cyclists can produce over 400 watts for the same time period. These pros are even capable of hitting 1,000 watts for short bursts of time on a steep uphill – roughly enough power to run a microwave oven. But not all of the energy a Tour de France cyclist puts into his bike gets turned into forward motion. Cyclists battle air resistance and frictional losses between their wheels and the road. They get help from gravity on downhills but they have to fight gravity while climbing. I incorporate all of the physics associated with cyclist power output as well as the effects of gravity, air resistance and friction into my model. Using all that, I estimate that a typical Tour de France winner needs to put out an average of about 325 watts over the roughly 80 hours of the race. Recall that most recreational cyclists would be happy if they could produce 300 watts for just 20 minutes!  Turning food into milesSo where do these cyclists get all this energy from? Food, of course! But your muscles, like any machine, can't convert 100% of food energy directly into energy output – muscles can be anywhere between 2% efficient when used for activities like swimming and 40% efficient in the heart. In my model, I use an average efficiency of 20%. Knowing this efficiency as well as the energy output needed to win the Tour de France, I can then estimate how much food the winning cyclist needs. Top Tour de France cyclists who complete all 21 stages burn about 120,000 calories during the race – or an average of nearly 6,000 calories per stage. On some of the more difficult mountain stages – like this year's Stage 12 – racers will burn close to 8,000 calories. To make up for these huge energy losses, riders eat delectable treats such as jam rolls, energy bars and mouthwatering "jels" so they don't waste energy chewing. Tadej Pogačar won both the 2021 and 2020 Tour de France and weighs only 146 pounds (66 kilograms). Tour de France cyclists don't have much fat to burn for energy. They have to keep putting food energy into their bodies so they can put out energy at what seems like a superhuman rate. So this year, while watching a stage of the Tour de France, note how many times the cyclists eat – now you know the reason for all that snacking. [You're smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation's authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter.] This is an updated version of a story originally published on June 24, 2021. John Eric Goff does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |

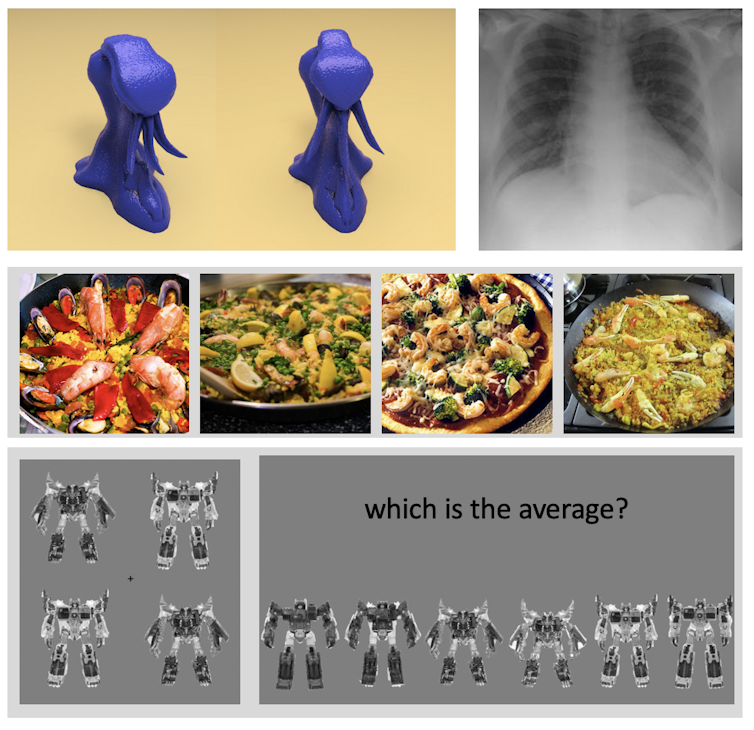

| Posted: 30 Jun 2022 05:23 AM PDT  Like snowflakes, no two people are exactly the same. You're probably used to the idea that people differ substantially in personality and in cognitive abilities – skills like problem-solving or remembering information. In contrast, there's a widely held intuition that people vary far less in their ability to recognize, match or categorize objects. Many everyday tasks, hobbies and even critical jobs – like interpreting satellite imagery, matching fingerprints or diagnosing medical conditions – rely on these perceptual skills. The common expectation is that smart and motivated people who receive the appropriate training should eventually be able to excel at occupations that require hundreds of perceptual decisions every day. We are psychologists who measure how people compare on challenging perceptual tasks. Our research has found that this intuition that everyone has the same capacity for perceptual skills is not supported by the evidence. It's not a problem if you choose to spend every weekend bird-watching without ever getting very good at it – you may still get some fresh air and have fun. But when perceptual decisions influence safety, health or legal outcomes, there's a case for seeking people who can achieve the best possible performance. Our research suggests some people are just better than others at learning to discriminate things perceptually, whatever the objects may be. A general ability to recognize thingsClassic psychological studies at the turn of the 20th century discovered that performance across a range of cognitive tasks designed to test memory, math and verbal skills is correlated. In real life, this means someone who is great at sudoku is also likely to be good at memorizing their shopping list. This finding led to the modern notion of general intelligence, describing a collection of faculties that together predict a wide range of outcomes, from income to health and longevity. In a similar way, our studies reveal that those who are the best at bird recognition may also excel at plane identification, and they may also be the best at learning to spot tumors in chest X-rays. In other research, the same ability predicted better performance in reading musical notation or recognizing images of prepared food. Of course, people vary in their experience with birds or medical images. The more familiar you are with them, the better you are at recognizing them. Experience and training have an important role in how people make decisions based on visual information. But does everyone start on the same footing when they begin training? Does everyone start at square one?We were interested in whether everyone starts at about the same baseline of perceptual talent. To investigate this question, we measured people's abilities with artificial objects they had never seen, to prevent any advantage due to different levels of experience. In one large study, we assessed 246 people for 13 hours each, testing them on several tasks with six categories of computer-generated artificial objects. We asked people to remember and recognize objects, to match them, or to make judgments about some of their parts.  Our results across tasks like these repeatedly reveal that people vary as much in perceptual abilities as they do in cognitive skills. Using statistical methods historically applied to intelligence and personality tests, we found that over 89% of the differences between people in their performance with these different tasks and categories could be explained by a general ability. We called this ability "o" for object recognition and in honor of the "g" factor, which stands for similar statistical evidence for general intelligence. In follow-up studies, we've found that o applies in the same way to artificial and real objects, and that people with high o are better at computing summary statistics for groups of objects (such as estimating the "average" of several objects) and also better at recognizing objects by touch. You can compare yourself to others in this short demo. o is a distinct abilitySince it is so general, is o just another name for general intelligence? We don't think so. In one study, we found that neither IQ nor SAT scores predict recognition of novel objects. In other work, we found that o was distinct from g, but also from the personality trait of conscientiousness. This means that book smarts may not be enough to excel in domains that rely heavily on perceptual abilities. We tested this idea by measuring how good people with or without expertise in radiology were at detecting lung nodules in chest X-rays. Those with the highest o were better at this task, even after controlling for intelligence and experience in radiology. This finding demonstrates the added value of measuring o. Even when medical students are selected to be smart and provided with training, it may not guarantee the highest levels of performance in specializations that rely on perceptual skills. Many doors open when you demonstrate that you're cognitively talented, which seems only fair. But it is fair only to the extent that general intelligence is the best way – or even a sufficient way – to predict success in a given domain. Many have raised warnings that intelligence testing can lead to inequities in hiring or career placement tied to race, gender or socioeconomic status. Over the years, many thinkers have downplayed innate talents to emphasize environmental influences. They argued that success can be shaped through years of deliberate practice, programs to change one's attitudes about learning, or even hours of playing video games. But the evidence in favor of the influence of innate talents remains strong, and denying them or overpromising on the efficacy of environmental factors may sometimes be harmful. People can waste time and resources that could be better invested, and may run the risk of experiencing stigma if their efforts do not succeed because of factors they cannot control. One answer to this problem is to learn more about talents beyond those related to intelligence and then to make better use of them. Classical notions of intelligence may be just one factor of many that determine overall ability. An increased focus on perceptual abilities, specifically those that are general, could help reduce inequities. For instance, while differences in experience can drive sex differences in the recognition of objects in some familiar categories, we've found no such differences in the general ability o. The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |

| Posted: 30 Jun 2022 05:23 AM PDT  "Are you going to run out of water?" is the first question people ask when they find out I'm from Arizona. The answer is that some people already have, others soon may and it's going to get much worse without dramatic changes. Unsustainable water practices, drought and climate change are causing this crisis across the U.S. Southwest. States are drawing less water from the Colorado River, which supplies water to 40 million people. But levels in Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the river's two largest reservoirs, have dropped so low so quickly that there is a serious risk of one or both soon hitting "dead pool," a level when no water flows out of the dams. On June 14, 2022, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Camille Calimlim Touton warned Congress that the seven Colorado River Basin States – Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming – need to reduce their diversions from the Colorado River by 2 million to 4 million acre-feet in 2022. An acre-foot is enough water to cover an acre of land, about the size of a football field, with a foot of water – roughly 325,000 gallons. If the states don't come up with a plan by August 2022, Touton may do it for them. To achieve Touton's objective, states need to focus on the region's biggest water user: agriculture. Farmers consume 80% of the water used in the Colorado River Basin. As a longtime analyst of western water policy, I believe that solving this crisis will require a major intervention to help farmers use less water. Lawns in the desertIt's not an exaggeration to call the Southwest's water shortage a crisis. Declining river levels are compromising electricity generation from hydropower, which affects the power supply for millions of people. Farmers are fallowing fields and using less water on their crops. This, in turn, imperils food production already under global strain from the war in Ukraine. Drought conditions could wipe out endangered species, especially salmon. There is something profoundly unsettling about the lush green landscape in Southern California, a desert transformed by the power of water. The average annual rainfall at Los Angeles International Airport from 1944 to 2020 was 11.72 inches (30 centimeters). That's not much more than Tucson, Arizona, gets in the middle of the Sonoran Desert. Now, however, western states are imposing unprecedented restrictions on water use. On June 1, 2022, the Metropolitan Water District, wholesaler to 20 million Southern Californians, urgently called for a 35% reduction in water use. In response, the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power is limiting residents to watering their lawns twice a week, for eight minutes per session. Other providers allow just one weekly watering. The California Water Resources Control Board has ordered many farmers and San Francisco Bay-area cities to stop diverting water from the San Joaquin River system. Golf course operators are under substantial pressure to reduce water use. Focus on irrigationStill, agriculture uses far more water than lawns and golf courses. In 2017, U.S. farmers irrigated about 58 million acres (23 million hectares) of cropland, almost two-thirds of it in the West. In recent decades western farmers have significantly changed their irrigation practices. Many have switched from flood systems, which literally flood fields, to pressurized systems. Typically these are center pivots that apply water from sprinklers connected to a large arm that slowly moves around a core, creating those large, usually green circles that airplane passengers can see across the West. This shift reduces water losses from evaporation, percolation into the soil and runoff. In 2012, U.S. farmers used pressurized systems on 72% of their fields, up from 37% in 1984. That still leaves 28%, or 20 million acres (8 million hectares), that are flood irrigated. And center-pivot systems are not as efficient as drip or microirrigation, which delivers water directly to plants' root zone through hoses embedded in the soil. Drip irrigation delivers water slowly, reducing runoff and evaporation. Microirrigation systems use 20% to 50% less water than conventional sprinkler systems.  But drip systems are quite expensive, costing upwards of US$2,000 per acre. They are not cost-effective for farmers who grow low-value crops, such as alfalfa, and are prohibitively expensive for small farmers. Most farms that irrigate are small operations with fewer than 50 acres (20 hectares) and less than $150,000 in annual revenues. But large-scale farms, with annual revenues over $1 million, use about 60% of irrigated water. Bigger farms have the necessary capital to invest in sprinkler systems, but not necessarily enough to invest in highly efficient subsurface drip or microirrigation. Existing U.S. Department of Agriculture programs offer modest incentives, usually a maximum of $100 per acre – not enough to justify switching for most farmers. Balancing rural and urban needsHelping farmers switch to high-efficiency irrigation systems would benefit the entire Southwest. I propose a two-pronged approach. First, Congress would provide funding to the U.S. Department of Agriculture to offer farmers more generous financial incentives to switch to microirrigation systems. The 2021 infrastructure bill contains $8.3 billion to assist western states in adapting to drought and climate change. I believe that this financial aid, with support from the federal Bureau of Reclamation and the USDA, could persuade millions of American farmers to make the move. Second, to augment the federal program, state, municipal and local interests, including government agencies and private businesses, would create funds to underwrite the entire cost of converting farms to microirrigation. As I envision it, cities could offer to absorb 100% of the purchase and installation costs of microsystems in exchange for a percentage of the water that farmers would save by making the switch. A program that's cost-free to farmers would be far more attractive than existing federal programs. In my view, locally financed programs managed in collaboration with farm communities could reallocate a lot of water in a short time frame. This could be done through either a formal water rights transfer or short- or medium-term leases with farmers retaining water rights. In the past, farmers have been rightly suspicious when city representatives arrived with proposals to buy agricultural water. All too often, such transfers have triggered economic death spirals for rural communities. But it need not be so. Because farmers consume about 80% of western water, while residential, commercial and industrial use is less than 10%, I believe reducing agricultural consumption by a few percentage points would solve the municipal and industrial need for water. If farmers achieve this reduction thanks to increased efficiencies from microirrigation systems – paid for by cities – the farmers could grow as much product as they do now, with slightly less water. Making this shift could raise economic and technical challenges. For example, most farms would probably fallow or reduce production of low-value crops, such as alfalfa, which could affect animal feed prices. And one disadvantage of drip irrigation systems is that gophers love to gnaw on the plastic tubes, so farmers would need an animal control program. Nonetheless, I see voluntary, compensated water transfers as a strategy that would protect the long-term viability of rural communities and keep the taps flowing in western cities. Limits on watering lawns won't solve the West's water crisis. Robert Glennon does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |

| Posted: 30 Jun 2022 05:22 AM PDT  It's clear that the Supreme Court's ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization will make it harder for women to get an abortion across much of the United States. But there are other kinds of laws – not related to abortion – that already control the decisions women make during pregnancy. In this scenario, a state concludes a pregnant woman's conduct, mostly related to substance use, might harm the fetus they are carrying. These women are then forced into mandatory treatment or jail. Most of the women affected by these laws are poor, and disproportionately Black or Latina. I am a law professor who studies poverty policy in the U.S. I think it is key to understand that the Dobbs ruling not only allows state legislatures to limit women's ability to get an abortion, but it also invites state legislatures to pass more laws that control pregnant women's behavior.  States' history of punishing women during pregnancyAt least 40 states have used a variety of laws to punish the behavior of pregnant women over the last five decades. These cases usually involve a woman whom the state believes is harming her fetus by taking drugs or abusing alcohol. For example, as I describe in my book coming out in September, Tennessee prosecuted and punished about 120 women from 2014 to 2016 for harming the fetuses they were carrying when they took narcotics during their pregnancies. In total, scholars, journalists and activists have documented over 1,700 prosecutions and other interventions, like jailing a woman who refuses to enter treatment, against pregnant women from 1973 to 2020. States have prosecuted women, in these cases, for assault, chemical endangerment, child abuse and murder. Although in most cases these laws were originally passed to criminalize other people's attacks against pregnant women, prosecutors have used these laws to prosecute pregnant women themselves. While one might think that bringing prosecutions and jailing women to protect a fetus from her mother's drug use might be an effective, if extreme, way to protect the fetus, virtually every major medical organization disagrees. Research shows that incarcerating pregnant women because of substance use is not effective as a deterrent and can actually harm both the pregnant person and fetus. One reason is that there is significant anecdotal evidence that jails and prisons lack basic prenatal care services. The vast majority of jails also do not provide adequate health care services for pregnant patients with substance use disorders. Another reason is that women who know that they might be punished if they go to the doctor are likely to avoid the doctor, a result that can harm both mother and child. Instead, the American Medical Association and other expert groups recommend that the government spend more money setting up specialized treatment programs for pregnant and breastfeeding women with substance use disorders. Jailing pregnant women to protect their fetusesIn addition to criminal prosecutions, there are at least two other kinds of state laws that let judges involuntarily commit and jail pregnant women. First, judges in Tennessee have used state law to jail pregnant women who are on probation when the court has evidence that the woman is using drugs during pregnancy. As one court staff person explained to me, when a criminal court judge finds out that a pregnant woman who is on probation has failed a drug test, the court issues an order putting her in jail. As that particular Tennessee court worker explained to me in 2018, "A lot of babies have been saved that way." Second, in Wisconsin, South Dakota and Minnesota, legislatures have authorized the involuntary commitment, either in medical facilities or jail, of pregnant women who use drugs or alcohol during pregnancy. For example, in Wisconsin, the state can investigate the welfare of an "unborn child" and can order a woman to comply with drug treatment and services. If she refuses, the court can mandate that this woman is arrested and jailed. Because child welfare records are confidential, we do not know precisely how many cases like these exist. In one court case, the state of Wisconsin revealed that, from 2006 to 2017, 467 women were found to have committed "unborn child abuse," meaning that the state believed these women harmed their fetuses.  Dobbs invites states to pass more laws like theseIn one sense, Dobbs has little impact on these kinds of laws. Roe v. Wade and the 1992 case that reinforced its precedent, Planned Parenthood v. Casey, never stopped these prosecutions and interventions, and they would have continued even if the Supreme Court didn't overturn these rulings. On the other hand, it is clear that the Dobbs ruling grants state legislatures new license to pass laws in the name of fetal protection. Prior to Dobbs, constitutional law balanced the rights of a pregnant woman to control her pregnancy against the state's legitimate interest in the fetus. That is why, under Roe and Casey, a woman's interest in controlling her body outweighed the state's interest in the fetus early in a woman's pregnancy. As a pregnancy progressed, the balance shifted away from protecting the woman's autonomy and toward protecting the state's interest in the fetus. But as Supreme Court Justices Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor explain in their dissenting opinion with the Dobbs ruling, "the Court discards that balance. It says that from the very moment of fertilization, a woman has no rights to speak of." So who will look out for the rights of either the mother or the fetus? The Supreme Court is clear. As Justice Brett Kavanaugh explained in his concurring opinion, "those difficult moral and policy questions will be decided" not by the court, but "by the people and their elected representatives through the constitutional processes of democratic self-government." After Dobbs, as the dissenting judges explained, it seems the states have all the power they need to pass and enforce new laws that punish pregnant women, whether or not they want to get an abortion. Wendy Bach does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |

| Posted: 30 Jun 2022 05:22 AM PDT  It is a central principle of law: Courts, including the Supreme Court, are supposed to follow earlier decisions – precedent – to resolve current disputes. But on rare occasions, Supreme Court justices conclude that one of the court's past constitutional precedents has to go, so they overrule it. This is exactly what happened in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, when the court overturned Roe v. Wade, the 1973 ruling recognizing a constitutional right to abortion. For years the court had been building up a theory of precedent reversal that would justify overturning Roe, among other precedents it did not like, and the draft opinion leaked in early 2022 foreshadowed this decision. The justices who voted to overrule the Roe precedent provided the reasoning behind their decision to reverse a longstanding ruling and declare abortion rights are not protected by the U.S. Constitution. Their explanations also open up the possibility of more reversals of precedent in the future. Why precedent?Over the centuries, courts have stated many reasons they should adhere to precedent. First is the idea of equity or justice, under which "like cases should be decided alike." If a court in the past reviewed a particular set of facts and decided a case in a specific way, fairness dictates it should decide another similar case the same way. Adhering to precedent promotes uniformity and consistency in the law. In addition, precedent promotes judicial efficiency: Courts do not have to decide from scratch every time. They can look at similar cases from the past and base their reasoning on those decisions. Finally, following precedent promotes predictability in the law and protects people who have come to rely on past decisions as a guide for their behavior. Reversing precedent is unusualThe Supreme Court rarely overturns its past decisions or precedents. In my book, "Constitutional Precedent in Supreme Court Reasoning," I point out that from 1789 to 2020, there were 25,544 Supreme Court opinions and judgments after oral arguments. The court has reversed its own constitutional precedents only 145 times – barely 0.05%. The court's historic periods are often characterized by who led it as chief justice. From 1953 until 2020, under the successive leadership of Chief Justices Earl Warren, Warren Burger, William Rehnquist and now John Roberts, the court overturned constitutional precedent 32, 32, 30 and 15 times, respectively. That is well under 1% of decisions handled during each period in the court's history. When is precedent overturned?For most of its history, the court changed its mind only when it thought past precedent was unworkable or no longer viable, perhaps eroded by its subsequent opinions or by changing social conditions. In some cases, reversal happened when the court simply thought it got it wrong in the past. Not all precedents are equal, and several current Supreme Court justices have in the past been open to overturning even long-standing rulings that interpret the Constitution. Beginning with the Rehnquist court, justices became more willing to reject precedents they thought were badly reasoned, simply wrong or inconsistent with their own sense of the constitutional framers' intentions. Justice Clarence Thomas has taken this position on abortion. Justice Amy Coney Barrett, during her Senate confirmation hearing, argued that Roe is not a so-called superprecedent, a decision so important or foundational that it cannot be overturned.  Roberts has been willing to overturn settled law when he thinks the original opinion was not well argued. He did so in Citizens United, a 2010 decision overturning two major campaign finance decisions, Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce from 1989 and part of the 2003 McConnell v. FEC decision. In 2020, Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh in Ramos v. Louisiana went out of their way to explain and justify their views on when constitutional precedent may be overturned. They echoed Justice Samuel Alito's discussion in 2018 in Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees Council Number 31. All three justices said constitutional precedent is merely a matter of court policy or discretion, more easily overturned than a precedent about a law. Sometimes, they said, constitutional precedents can be overruled if later judges view them as wrongly decided or reasoned. All of these comments foreshadowed the Dobbs opinion. Reversing Roe v. WadeRoe v. Wade was an important precedent. In 1973, the Supreme Court ruled that women have a right to terminate their pregnancies. That right was reaffirmed in 1991 in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, with Justices Sandra Day O'Connor, Anthony Kennedy and David Souter noting that an entire generation of women came of age relying upon their right to control their bodies and terminate pregnancies in most circumstances. The justices said it would be wrong to upset that expectation, declaring "An entire generation has come of age free to assume Roe's concept of liberty in defining the capacity of women to act in society, and to make reproductive decisions." In the Dobbs decision, Alito, who wrote the majority opinion, said "Roe and Casey must be overruled." His justification was that abortion rights are not mentioned in the Constitution, and protection of abortion rights is not "deeply rooted in this Nation's history and tradition." He also said Roe was not essential to the United States' "scheme of ordered liberty" – or sense of personal freedom. Alito also argued that Roe was "was egregiously wrong from the start. Its reasoning was exceptionally weak, and the decision has had damaging consequences. And far from bringing about a national settlement of the abortion issue, Roe and Casey have enflamed debate and deepened division." For Alito and the justices who joined his opinion – Thomas, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Barrett – the weakness and wrongness of the Roe decision simply outweighed the importance of the fact that women had relied on it for decades when making important personal decisions. Kavanaugh wrote a concurring opinion that argued for reversing Roe for additional reasons. He wrote that the Constitution is silent on abortion – and therefore neutral on its constitutionality or unconstitutionality – so the court should be silent also. He declared that Roe was "egregiously wrong" and said it "has caused significant negative jurisprudential or real-world consequences." Finally, and perhaps most dramatically, Thomas' concurrence declared that not only was Roe wrong, but the entire idea of the court recognizing the existence of constitutional rights not explicitly found in the text of the Constitution was flawed, an inappropriate expansion of rights that is known as substantive due process. Thomas called for the court to reconsider the 1964 decision on the right of any couple to use birth control, the 2002 decision on the right of same-sex couples to engage in private consensual sexual acts and the 2014 decision on the right of same-sex couples to marry. All of these are presumably settled precedents. However, given Dobbs and the reasoning the various justices in the majority have offered, they too, along with others, could be candidates for reversal. This is an updated version of an article originally published Sept. 20, 2021. David Schultz does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |

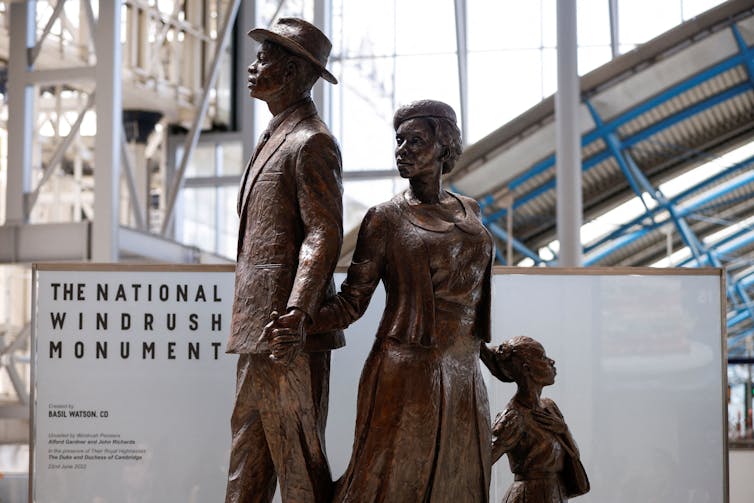

| Racial wealth gaps are yet another thing the US and UK have in common Posted: 30 Jun 2022 05:22 AM PDT  It's an old saying that Britain and America are two countries separated by a common language. But they are united by racial wealth gaps that formed at a similar time for related reasons. Black Britons of the "Windrush generation," arriving in Britain from the Caribbean between 1948 and 1973, and Black Americas from the Great Migration of the 1940s-1970s encountered similar disadvantages that were reproduced in the last 50 years. Today, examining household assets, Black Britons of Caribbean backgrounds have 20 pence on the £1 compared to white Britons. Black Britons of African background – more recently arrived in Britain – have just 10 pence on the £1 compared to white Britons. In the U.S., Black Americans have assets about 15 to 20 cents on the $1 compared to whites. This is in large part the result of policymakers in both countries putting up roadblocks to Black advancement at the time they instituted policies to grow the middle class. In my view as a historian of slavery, capitalism and African American inequality, it's not just the long shadow of enslavement, which Britain abolished in its western colonies in 1833 and the U.S. ended in 1865 with passage of the 13th Amendment. When Black members of the British Commonwealth moved to Britain starting in 1948 and African Americans moved from the South to the North and West, they encountered new obstacles. The long struggle for equal job opportunities has had a lasting effect on the ability to accrue wealth and pass it on to subsequent generations. The British illusion of opportunityThe moment Black opportunity in Britain opened up was June 22, 1948, when the British ship Empire Windrush docked on the River Thames, disembarking 802 passengers of Caribbean background in England. They led the first sustained Black migration, the Windrush generation, mostly Black and Asian, arriving in Britain between 1948 and 1973. U.K. employers wanted their labor amid a post-World War II shortage. About a third of Windrush passengers were veterans of the British forces who served in World War II and recruited by employers for skilled jobs. Caribbean women, for instance, became vital to the new U.K. National Health Service as nurses, cooks and cleaners, many caring for patients by night and families by day.  But, as British journalist Afua Hirsch argues, they faced persistent discrimination in housing and jobs. Employers wanted them as laborers, not neighbors, and they faced hostility from those determined to "Keep England White." When a Bristol bus company refused to employ Black conductors and drivers, Black workers counter-organized, staging a successful Bristol bus boycott against employment discrimination. Such action led to the 1964 Campaign Against Racial Discrimination, which helped catalyze the 1965 U.K. Race Relations Act banning public discrimination and made promoting hatred based on "colour, race, or ethnic or national origins" a crime. Meanwhile, civil rights leaders such as Olive Morris fought for economic inclusion through organizations like the Black Workers Movement. These efforts helped include Black workers in unionized industry and led to wage gains. The American allure of opportunityWhile the Windrush generation took shape, African Americans too were moving north and west in search of opportunity. Journalist Isabel Wilkerson contends that "the Great Migration had more in common with the vast movements of refugees from famine, war, and genocide in other parts of the world." In the three decades following the Great Depression, the American wage structure became more equal than at any time before or since, a process economic historians term "The Great Compression." Between 1940 and 1960, the distance between earners in the top 10% and bottom 90% narrowed by a third.  But policies giving white Americans a boost up the ladder tended to hamstring African Americans. Social Security initially excluded most Black workers. Union wages rose, but African Americans were underrepresented in union jobs. Home loan guarantees went to white families and specifically excluded Black-occupied properties in many U.S. cities. Redlining was the practice of denying loan guarantees to properties occupied by Black and other minority residents. It became a self-fulfilling prophesy of disinvestment and declining values. Meanwhile, post-WWII programs to improve social mobility, like the 1944 Servicemen's Readjustment Act, or GI Bill, largely benefited white veterans by expanding the middle class with job, college and home loan assistance. Historian Matthew F. Delmont argues that "by funneling resources to white veterans and denying loans to Black veterans, the GI Bill intensified the racial wealth gap and shared the terrain of opportunity in America for decades after the war." In the 1960s, legal barriers gave way to what African American Studies scholar Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor calls "predatory inclusion" in home ownership, finance and education. By the time Black Americans began to narrow a persistent wealth gap, the economy was paying diminishing returns to workers. The wealth-to-earnings ratio rose in the U.S. and U.K. after 1973, and Black Americans who had recently climbed one or two rungs on the ladder started to move backward relative to whites. Britain's failed promiseBy the 1970s, multicultural Britain had taken shape. As British sociologist Paul Gilroy argues, Black Britain, including people of African and South Asian descent, had become a complex of class and cultures as diverse as England's imperial geography that once included colonies in Asia, Africa and the Americas. But diversity didn't mean inclusion. Just as Black working-class Britons were making gains in unionized industry, that rung of the ladder cracked. Starting in the late 1970s, factories closed or moved offshore, and ways into the middle class narrowed as the U.K. and U.S. pursued a strategy of more privatization and less government spending on social services. Union strength declined across sectors, and worker wages stagnated. Many Black Britons were trapped in segregated neighborhoods and didn't reap gains from rising home values. Today, 2 in 3 white British families own homes compared to 2 in 5 Black British families of Caribbean background and 1 in 5 Black British families of African background. By the 2000s, those who lacked capital or technological skills in Britain had a hard time climbing up the economic ladder. Income inequality soared between 1979 and the early 2000s, reaching levels not seen since before WWII. America's reinvention of inequalityMeanwhile in the United States, legal barriers fell while the economy changed in ways that disadvantaged Black workers in new ways. In 1979 the average Black worker earned 82 cents on the dollar compared to white counterparts. By 2000, the earnings gap widened to 77 cents on the dollar. The Great Recession of 2008 destroyed half of Black wealth, and in 2015 an estimated 1.5 million Black American men were missing from the economy, having died early, been incarcerated or shut out of the employment market – 8.2% of working-age African American men compared with 1.6% of white men in the same age range. Despite wealth gains since 2016, Black wealth was more vulnerable and harder to accumulate. The earnings gap remains wide today. Black women workers in the U.S. earn 79 cents on the dollar compared to white women, and Black men earn 87% of white men's wages. Discrimination across the AtlanticIn the U.K., just before the pandemic, Black Britons of African and Caribbean background earned 85% and 87% of the wages of white Britons, respectively. According to a study by two leading U.K. inequality think tanks, British women of color endure "intersecting structural barriers and discrimination faced at every point of the career pipeline, from school to university to employment." U.K. wealth is largely white, resulting from the "history of economic relations between Britain and the rest of the world, especially Africa, the Caribbean and Asia," according to the Runnymede Trust, an inequality think tank. Over the last 80 years, the underbelly of Britain and America is that both countries reinvented racial economic disadvantages. Instead of making their economies fundamentally fair, racial exclusions gave way to inclusion that came with surcharges on opportunity while failing to rectify past wrongs. Calvin Schermerhorn does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |