Home – The Conversation |

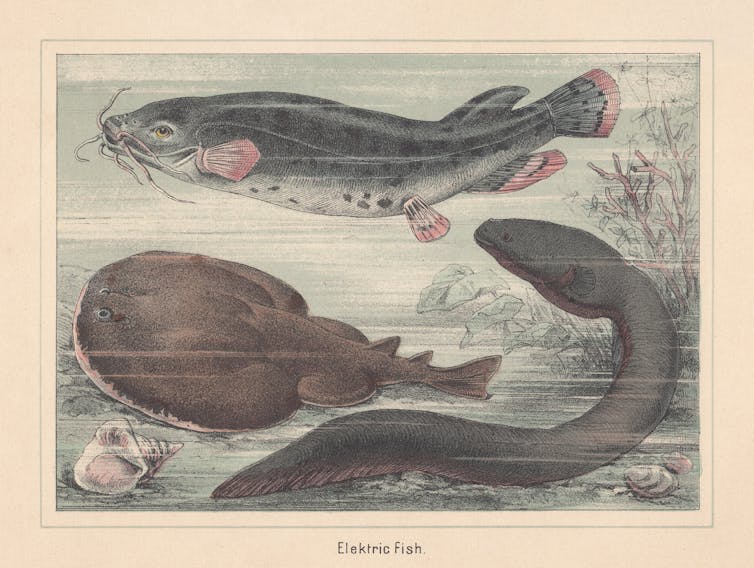

- Electric eels inspired the first battery two centuries ago and now point a way to future battery technologies

- Nonprofit drugmaker Civica Rx is taking aim at the high insulin prices harming people with diabetes

- Elon Musk is wrong: research shows content rules on Twitter help preserve free speech from bots and other manipulation

- What does an octopus eat? For a creature with a brain in each arm, whatever's within reach

- Disney hasn't found itself in this much trouble since 1941

- ADHD in adults is challenging but highly treatable – a clinical psychologist explains

- Forgotten insurrection clause of 14th Amendment used to force GOP members of Congress to defend their actions on Jan. 6

- Florida Republicans' row with Mickey Mouse highlights widening gap between historical BFFs GOP and corporate America

| Posted: 09 May 2022 12:07 PM PDT  As the world's need for large amounts of portable energy grows at an ever-increasing pace, many innovators have sought to replace current battery technology with something better. Italian physicist Alessandro Volta tapped into fundamental electrochemical principles when he invented the first battery in 1800. Essentially, the physical joining of two different materials, usually metals, generates a chemical reaction that results in the flow of electrons from one material to the other. That stream of electrons represents portable energy that can be harnessed to generate power. The first materials people employed to make batteries were copper and zinc. Today's best batteries – those that produce the highest electrical output in the smallest possible size – pair the metal lithium with one of several different metallic compounds. There have been steady improvements over the centuries, but modern batteries rely on the same strategy as that of Volta: pair together materials that can generate an electrochemical reaction and snatch the electrons that are produced.  But as I describe in my book "Spark: The Life of Electricity and the Electricity of Life," even before humanmade batteries started generating electric current, electric fishes, such as the saltwater torpedo fish (Torpedo torpedo) of the Mediterranean and especially the various freshwater electric eel species of South America (order Gymnotiformes) were well known to produce electrical outputs of stunning proportions. In fact, electric fishes inspired Volta to conduct the original research that ultimately led to his battery, and today's battery scientists still look to these electrifying animals for ideas. Copying the eel's electric organPrior to Volta's battery, the only way for people to generate electricity was to rub various materials together, typically silk on glass, and to capture the resulting static electricity. This was neither an easy nor practical way to generate useful electrical power. Volta knew electric fishes had an internal organ specifically devoted to generating electricity. He reasoned that if he could mimic its workings, he might be able to find a novel way to generate electricity.  The electric organ of a fish is composed of long stacks of cells that look very much like a roll of coins. So Volta cut out coinlike disks from sheets of various materials and started stacking them, in different sequences, to see if he could find any combination that would produce electricity. These stacking experiments kept yielding negative results until he tried pairing copper disks with zinc ones, while separating the stacked pairs with paper disks wetted with saltwater. This sequence of copper-zinc-paper fortuitously produced electricity, and the electrical output was proportionate to the height of the stack. Volta thought he had uncovered the secret of how eels generate their electricity and that he had actually produced an artificial version of the electric organ of fish, so he initially called his discovery an "artificial electric organ." But it was not. What really makes eels electrifyingScientists now know the electrochemical reactions between dissimilar materials that Volta discovered have nothing to do with the way an electric eel generates its electricity. Rather, the eel uses an approach similar to the way our nerve cells generate their electrical signals, but on a much grander scale. Specialized cells within the eel's electric organ pump ions across a semipermeable membrane barrier to produce an electrical charge difference between the inside versus the outside of the membrane. When microscopic gates in the membrane open, the rapid flow of ions from one side of the membrane to the other generates an electrical current. The eel is able to simultaneously open all of its membrane gates at will to generate a huge jolt of electricity, which it unleashes in a targeted fashion upon its prey. Electric eels don't shock their prey to death; they just electrically stun it before attacking. An eel can generate hundreds of volts of electricity (American household outlets are 110 volts), but the eel's voltage does not push enough current (amperage), for a long enough time, to kill. Each electric pulse from an eel lasts only a couple thousandths of a second and delivers less than 1 amp. That's just 5% of household amperage. This is similar to how electric fences work, delivering very short pulses of high-voltage electricity, but with very low amperage. They thus shock but do not kill bears or other animal intruders that try to get through them. It is also similar to a modern Taser electroshock weapon, which works by quickly delivering an extremely high-voltage pulse (about 50,000 volts) carrying very low amperage (just a few milliamps). Modern attempts to mimic the eelLike Volta, some modern electrical scientists searching to transform battery technology find their inspiration in electric eels. A team of scientists from the United States and Switzerland is currently working on a new type of battery inspired by eels. They envision that their soft and flexible battery might someday be useful for internally powering medical implants and soft robots. But the team admits they have a long way to go. "The electric organs in eels are incredibly sophisticated; they're far better at generating power than we are," lamented Michael Mayer, a team member from the University of Fribourg. So, the eel research continues.  In 2019, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to the three scientists who developed the lithium-ion battery. In conferring the award, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences asserted that the awardees' work had "laid the foundation of a wireless, fossil fuel-free society." The "wireless" part is definitely true, since lithium-ion batteries now power virtually all handheld wireless devices. We'll have to wait and see about the "fossil fuel-free society" claim, because today's lithium-ion batteries are recharged with electricity often generated by burning fossil fuels. No mention was made of the contributions of electric eels. [Over 150,000 readers rely on The Conversation's newsletters to understand the world. Sign up today.] Later that same year, though, scientists from the Smithsonian Institution announced their discovery of a new South American species of electric eel; this one is notably the strongest known bioelectricity generator on Earth. Researchers recorded the electrical discharge of a single eel at 860 volts, well above that of the previous record-holding eel species, Electrophorus electricus, that clocked in at 650 volts, and 200-fold higher that the top voltage of a single lithium-ion battery (4.2 volts). Just as we humans try to congratulate ourselves on the greatness of our latest portable energy source, the electric eels continue to humble us with theirs. Timothy J. Jorgensen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |

| Nonprofit drugmaker Civica Rx is taking aim at the high insulin prices harming people with diabetes Posted: 09 May 2022 05:05 AM PDT  Doctors have been treating diabetes with insulin since 1922. A century later, about 1 in 5 of the 37 million Americans living with diabetes take this medication – a hormone that helps cells absorb sugar from the blood. This medication helps avert a host of medical problems including heart disease, kidney disease and stroke. Some 1.6 million Americans living with Type 1 diabetes, a condition in which people don't produce any insulin, depend on it for their survival. So do millions more people with Type 2 diabetes – a condition in which the body doesn't make enough insulin. But an estimated 1 in 4 of the Americans who need it have so much trouble affording this lifesaving medication that they skimp on doses because insulin prices have been skyrocketing for years. For example, the full cost – not counting insurance coverage – of about one month's worth of a commonly used kind of insulin called glargine has nearly tripled from US$99 in 2010 to $284 in 2022. The exact amount Americans pay for insulin varies quite widely, depending on their insurance coverage and which version of the medication they're prescribed. Civica Rx, a nonprofit that manufactures generic drugs, is trying to help solve this problem. It's planning to produce generic insulin for no more than $30 for a month's worth of the drug at a factory being built in Petersburg, Virginia. Eventually the drugmaker intends to sell all three of the most popular kinds of insulin, starting in 2024 with glargine. Based on my research regarding the pharmaceutical industry and my work as a doctor who treats patients with diabetes, I believe this effort, announced in March 2022, may greatly increase access to insulin for hundreds of thousands of people who need but can't currently afford it. Generic insulin competition is limitedAmericans rely on robust competition from low-cost generic drugs to make pharmaceutical products more affordable. This system has historically been more successful with blockbuster drugs like atorvastatin – a cholesterol-controlling drug better known by the brand name Lipitor – and azithromycin – an antibiotic sold under the brand name Zithromax. Unfortunately, this system has failed to restrain increases in insulin prices, which are far higher in the United States than other countries. One reason this has been the case has to do with the fact that insulin is a biologic drug, meaning that it's produced using DNA technology by living organisms. Biologic drugs are harder to manufacture and are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration in a different manner than more conventional drugs. Seeing reasons for optimismI'm excited about this initiative because it promises to increase access to all people who require insulin in the U.S., regardless of insurance status or where they buy medications. One reason is that Civica Rx is a nonprofit that will be more able than private-sector drugmakers to put the interests of those who pay for insulin – patients and health insurers – ahead of investors'. Another is its pricing strategy. Civica Rx plans to charge only about 20% of the list prices for brand-name insulin products. Walmart and some other big-box retailers already sell insulin at a discount, but their prices are still higher than what the nonprofit plans to charge. And findings from my own research suggest that intellectual property protections will not likely be a substantial barrier to Civica's efforts. I'm also optimistic because of support from large insurers like Anthem and Blue Cross Blue Shield Association for this effort. It's reassuring that Civica Rx's leadership includes many people with decades of experience in the pharmaceutical industry and in health policy. But I see some reasons to be less optimistic. First, there have been prior attempts to manufacture generic insulin in the U.S. None have succeeded. Another possibility is that brand-name insulin manufacturers may try to push doctors to prescribe newer patent-protected versions of insulin, which would be harder for Civica Rx to market as a generic – at least initially. Success is far from guaranteed, given that the established players all have a strong financial interest in seeing Civica's efforts fail. Lawmakers are taking actionSeveral state legislatures have also tried to deal with this problem. Some have enacted laws mandating drug price transparency and provided funds to guarantee emergency access to insulin.  But to date these assorted responses have failed to lower prices for brand-name insulin products, although I think it's possible that prices would have risen faster without them. Congress is also responding. Four weeks after Civica Rx announced its plans to produce insulin at well below current prices, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill that would limit insulin copays to $35 for insured patients. This measure was also in President Joe Biden's stalled Build Back Better spending plan. The House bill would leave out many patients – most notably the uninsured. But this measure would also mark a positive step should the Senate follow suit. People living with insulin-dependent diabetes have been waiting a long time for someone to do something to make it more affordable. It looks like that time may finally be arriving. Through his University, Jing Luo receives funding from The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust and has previously received funding from Arnold Ventures. Both of these organizations have made contributions to Civica. |

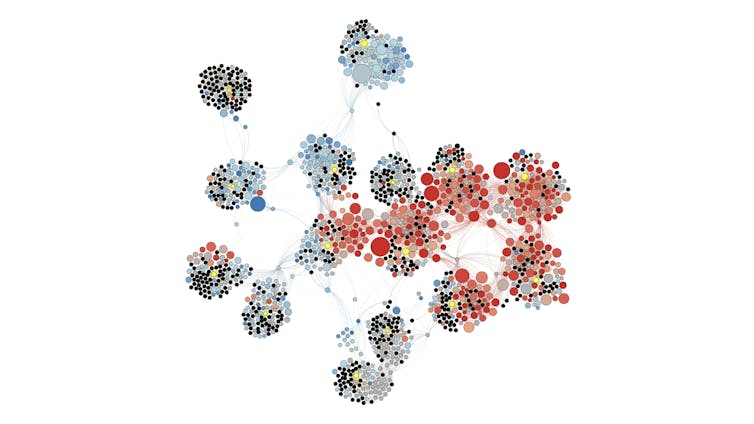

| Posted: 09 May 2022 05:05 AM PDT  Elon Musk's accepted bid to purchase Twitter has triggered a lot of debate about what it means for the future of the social media platform, which plays an important role in determining the news and information many people – especially Americans – are exposed to. Musk has said he wants to make Twitter an arena for free speech. It's not clear what that will mean, and his statements have fueled speculation among both supporters and detractors. As a corporation, Twitter can regulate speech on its platform as it chooses. There are bills being considered in the U.S. Congress and by the European Union that address social media regulation, but these are about transparency, accountability, illegal harmful content and protecting users' rights, rather than regulating speech. Musk's calls for free speech on Twitter focus on two allegations: political bias and excessive moderation. As researchers of online misinformation and manipulation, my colleagues and I at the Indiana University Observatory on Social Media study the dynamics and impact of Twitter and its abuse. To make sense of Musk's statements and the possible outcomes of his acquisition, let's look at what the research shows. Political biasMany conservative politicians and pundits have alleged for years that major social media platforms, including Twitter, have a liberal political bias amounting to censorship of conservative opinions. These claims are based on anecdotal evidence. For example, many partisans whose tweets were labeled as misleading and downranked, or whose accounts were suspended for violating the platform's terms of service, claim that Twitter targeted them because of their political views. Unfortunately, Twitter and other platforms often inconsistently enforce their policies, so it is easy to find examples supporting one conspiracy theory or another. A review by the Center for Business and Human Rights at New York University has found no reliable evidence in support of the claim of anti-conservative bias by social media companies, even labeling the claim itself a form of disinformation. A more direct evaluation of political bias by Twitter is difficult because of the complex interactions between people and algorithms. People, of course, have political biases. For example, our experiments with political social bots revealed that Republican users are more likely to mistake conservative bots for humans, whereas Democratic users are more likely to mistake conservative human users for bots. To remove human bias from the equation in our experiments, we deployed a bunch of benign social bots on Twitter. Each of these bots started by following one news source, with some bots following a liberal source and others a conservative one. After that initial friend, all bots were left alone to "drift" in the information ecosystem for a few months. They could gain followers. They acted according to an identical algorithmic behavior. This included following or following back random accounts, tweeting meaningless content and retweeting or copying random posts in their feed. But this behavior was politically neutral, with no understanding of content seen or posted. We tracked the bots to probe political biases emerging from how Twitter works or how users interact.  Surprisingly, our research provided evidence that Twitter has a conservative, rather than a liberal bias. On average, accounts are drawn toward the conservative side. Liberal accounts were exposed to moderate content, which shifted their experience toward the political center, while the interactions of right-leaning accounts were skewed toward posting conservative content. Accounts that followed conservative news sources also received more politically aligned followers, becoming embedded in denser echo chambers and gaining influence within those partisan communities. These differences in experiences and actions can be attributed to interactions with users and information mediated by the social media platform. But we could not directly examine the possible bias in Twitter's news feed algorithm, because the actual ranking of posts in the "home timeline" is not available to outside researchers. Researchers from Twitter, however, were able to audit the effects of their ranking algorithm on political content, unveiling that the political right enjoys higher amplification compared to the political left. Their experiment showed that in six out of seven countries studied, conservative politicians enjoy higher algorithmic amplification than liberal ones. They also found that algorithmic amplification favors right-leaning news sources in the U.S. Our research and the research from Twitter show that Musk's apparent concern about bias on Twitter against conservatives is unfounded. Referees or censors?The other allegation that Musk seems to be making is that excessive moderation stifles free speech on Twitter. The concept of a free marketplace of ideas is rooted in John Milton's centuries-old reasoning that truth prevails in a free and open exchange of ideas. This view is often cited as the basis for arguments against moderation: accurate, relevant, timely information should emerge spontaneously from the interactions among users. Unfortunately, several aspects of modern social media hinder the free marketplace of ideas. Limited attention and confirmation bias increase vulnerability to misinformation. Engagement-based ranking can amplify noise and manipulation, and the structure of information networks can distort perceptions and be "gerrymandered" to favor one group. As a result, social media users have in past years become victims of manipulation by "astroturf" causes, trolling and misinformation. Abuse is facilitated by social bots and coordinated networks that create the appearance of human crowds. We and other researchers have observed these inauthentic accounts amplifying disinformation, influencing elections, committing financial fraud, infiltrating vulnerable communities and disrupting communication. Musk has tweeted that he wants to defeat spam bots and authenticate humans, but these are neither easy nor necessarily effective solutions. Inauthentic accounts are used for malicious purposes beyond spam and are hard to detect, especially when they are operated by people in conjunction with software algorithms. And removing anonymity may harm vulnerable groups. In recent years, Twitter has enacted policies and systems to moderate abuses by aggressively suspending accounts and networks displaying inauthentic coordinated behaviors. A weakening of these moderation policies may make abuse rampant again. Manipulating TwitterDespite Twitter's recent progress, integrity is still a challenge on the platform. Our lab is finding new types of sophisticated manipulation, which we will present at the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media in June. Malicious users exploit so-called "follow trains" – groups of people who follow each other on Twitter – to rapidly boost their followers and create large, dense hyperpartisan echo chambers that amplify toxic content from low-credibility and conspiratorial sources. Another effective malicious technique is to post and then strategically delete content that violates platform terms after it has served its purpose. Even Twitter's high limit of 2,400 tweets per day can be circumvented through deletions: We identified many accounts that flood the network with tens of thousands of tweets per day. We also found coordinated networks that engage in repetitive likes and unlikes of content that is eventually deleted, which can manipulate ranking algorithms. These techniques enable malicious users to inflate content popularity while evading detection. Musk's plans for Twitter are unlikely to do anything about these manipulative behaviors. Content moderation and free speechMusk's likely acquisition of Twitter raises concerns that the social media platform could decrease its content moderation. This body of research shows that stronger, not weaker, moderation of the information ecosystem is called for to combat harmful misinformation. It also shows that weaker moderation policies would ironically hurt free speech: The voices of real users would be drowned out by malicious users who manipulate Twitter through inauthentic accounts, bots and echo chambers. Filippo Menczer receives funding from Knight Foundation, Craig Newmark Philanthropies, Open Technology Fund, and DoD. He owns a Tesla. |

| What does an octopus eat? For a creature with a brain in each arm, whatever's within reach Posted: 09 May 2022 05:05 AM PDT   Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you'd like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

The octopus is one of the coolest animals in the sea. For starters, they are invertebrates. That means they don't have backbones like humans, lions, turtles and birds. That may sound unusual, but actually, nearly all animals on Earth are invertebrates – about 97%. Octopuses are a specific type of invertebrate called cephalopods. The name means "head-feet" because the arms of cephalopods surround their heads. Other types of cephalopods include squid, nautiloids and cuttlefish. What do they eat?As marine ecologists, we conduct research on how ocean animals interact with each other and their environments. We've mostly studied fish, from lionfish to sharks, but we have to confess we remain captivated by octopuses. What octopuses eat depends on what species they are and where they live. Their prey includes gastropods, like snails and sea slugs; bivalves, like clams and mussels; crustaceans, like lobsters and crabs; and fish. To catch their food, octopuses use lots of strategies and tricks. Some octopuses wrap their arms – not tentacles – around prey to pull them close. Some use their hard beak to drill into the shells of clams. All octopuses are venomous; they inject toxins into their prey to overpower and kill them. Where do they live?There are about 300 species of octopus, and they're found in every ocean in the world, even in the frigid waters around Antarctica. A special substance in their blood helps those cold-water species get oxygen. It also turns their blood blue. You can find octopuses at different depths too. Some are found on warm tropical reefs just a few feet below the surface of the water. Others live deep in the sea, practically in the dark. The species that goes deepest is the dumbo octopus, spotted at 22,800 feet down – that's more than 4 miles (almost 7 kilometers). How smart are they?Octopuses are at the head of the class. They are among the smartest invertebrates on Earth. They have nine brains – one mini-brain in each arm and another in the center of their bodies. Each arm can independently taste, touch and perform basic movements, but all arms can also work together when prompted by the central brain. Octopuses put their brains to good use. They can solve mazes and puzzles, particularly when food is the reward. Sometimes they even outsmart people: At the New Zealand National Aquarium, Inky figured out how to sneak out of his tank and escape to the ocean through a drainpipe. How do they change color?Octopuses are experts at disguising themselves so they can blend in with their surroundings. One way they do it is by changing color. Special cells, called chromatophores, receive a signal from the brain to tighten the muscles to show more color, or loosen them to show less. Blue, green, pink, gray – they turn those colors and more to hide from predators, attract mates, draw in prey and warn enemies to stay away. Some species also change their skin texture, making it smoother or bumpier, so they can camouflage themselves in rocks and foliage. Some spray ink when confronted by predators like sharks; this allows the octopus enough time to swim to safety. The mimic octopus is particularly clever. It moves its arms in particular ways to imitate other ocean animals. For example, if it wants to look fierce, it extends two black-and-white striped arms out wide to look like the venomous sea snake. Or it flattens itself along the sea floor, arms next to its body, to look like a poisonous flatfish. The octopus at riskWhen confronting humans, an octopus tends to be nonaggressive – just as long as you give them space, like you would any ocean animal. Although octopuses have ways to avoid predators, they remain at risk from other threats: chemical pollutants, marine debris, habitat loss, overfishing and climate change. But all of us humans can help by making ocean-smart choices. That includes learning how to cut back on carbon emissions and using less plastic. Doing these things will help the octopus and other marine creatures not only survive, but thrive. Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you'd like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live. And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you're wondering, too. We won't be able to answer every question, but we will do our best. The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |

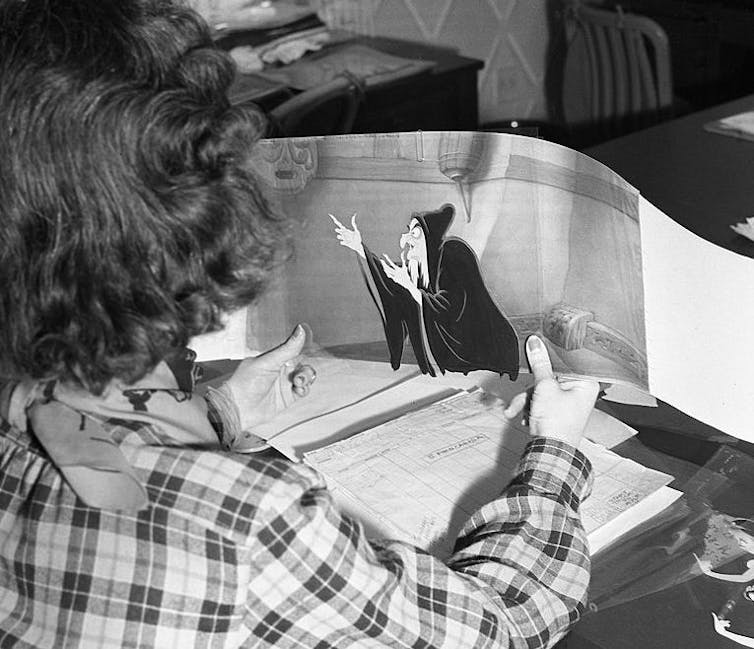

| Disney hasn't found itself in this much trouble since 1941 Posted: 09 May 2022 05:04 AM PDT  The family-friendly, controversy-averse Walt Disney Co. has walked into the buzz saw of the American culture wars, version 2022. In April, officials at Disney objected to a Florida law prohibiting instruction in sexual orientation and gender identity in kindergarten through third grade. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis responded by signing a bill revoking Disney's self-governing status, a unique arrangement in which the company operated like an independent fiefdom within the state. Traditionally, the custodians of one of Hollywood's most reliable cash machines have been careful to sidestep political minefields that might remind customers of a realm outside the Magic Kingdom. Better to wallow with Scrooge McDuck in the Money Bin than be caught in the crosshairs of Fox News chyrons. Only once before has the Disney brand gotten so entangled in a public relations briar patch – in 1941, when the original iteration of the company was confronted by an internal revolt that pitted the founding visionary against his pen-and-ink scriveners. The characters in the showdown were as colorful as any drawn on the studio's animation cels: union activists, gangsters, communists and anti-communists, and, not least, Walt Disney himself, who, dropping his avuncular persona, played a long game of political hardball and slow-burn payback. Workers grumble as Disney's star soarsEven then, Walt Disney inspired a special kind of awe around Hollywood. Billy Wilkerson, editor of The Hollywood Reporter, declared Disney "the only real genius in this business" in the Dec. 17, 1937, issue of the periodical. Disney was hailed as the father of the first sound cartoon, "Steamboat Willie" (1928); the first Technicolor cartoon, "Flowers and Trees" (1932); and the first feature-length cartoon, "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" (1937). "Snow White" marked the beginning of the extraordinary creative streak – "Pinocchio" and "Fantasia" in 1940, "Dumbo" the following year and 1942's "Bambi" – on which the Disney mythos would be built forever. In 1940, Disney plowed the profits from "Snow White" into a state-of-the-art animation studio in Burbank, California, where the comfort of his workers, so he said, was a high priority. "One of Walt Disney's greatest wishes has always been that his employees could work in ideal surroundings," read an advertisement in the Oct. 10, 1940, issue of The Hollywood Reporter. "The dean of animated cartoons realizes that a happy personnel turns out the best work." But even by the standards of exploitative Hollywood shop floors, Disney animators were overworked and underpaid. Forced to hunch over a drawing board for 10 hours a day, they had no desire to whistle while they worked. Instead, they wanted a strong union to negotiate on their behalf. Disney didn't want any of it.  The animators opted to be represented by the confrontational Screen Cartoonists Guild rather than the pro-management "company union," the American Society of Screen Cartoonists. "Disney cartoonists make less than house painters," charged the guild. "The girls are the lowest paid in the entire cartoon field. They earn from $16 to $20 a week, with very few earning as high as $22.50." The guild demanded a 40-hour, five-day work week, severance pay, paid vacation and a minimum wage scale ranging from $18 a week for apprentices to $250 for cartoon directors. To go nose to nose with Disney in the negotiations, the Screen Cartoonists Guild chose Herbert Sorrell of the Motion Picture Painters, Local 644, a longtime thorn in the side of studio management. Sorrell was a broad-shouldered union man of the old-school variety. A former heavyweight prize fighter, he was not afraid to mix it up on the picket line with cops and strikebreakers. Sorrell's footwork in the boxing ring – not to mention the brass knuckles he carried – came in handy. In the 1930s, labor organizing in Hollywood could be more hazardous than stunt work. Many studio heads had already cut sweetheart deals with the mobbed-up trade unions, notably the International Alliance of Theatrical and Stage Employees, run by a Chicago-schooled gangster named Willie Bioff. Animators put down their pensOn May 28, 1941, the Screen Cartoonists Guild called a strike, and hundreds of animators walked out on Disney. Brazenly violating Disney's copyright, the strikers repurposed Disney characters into pro-union spokesmen and paraded outside theaters playing Disney films. "There are no strings on me!" exclaimed Pinocchio in one placard. The slogans were as clever as the visuals: "Snow White and 700 Dwarfs," "3 Years College, 2 Years Art School, 5 Years Animation Equals 1 Hamburger Stand" and "Are We Mice or Men?" Disney was enraged. He claimed that Sorrell had threatened to turn the Burbank studio into a "dust bowl" unless he caved to the strikers' demands.  Behind the scenes, Disney offered the SCG a deal brokered by the gangster Willie Bioff. Disney then placed ads in the trade press saying he had made generous offers to "your leaders" – that would be Bioff – and had acceded to most of the strikers' demands. "I am positively convinced that Communistic agitation, leadership and activities have brought about this strike, and has persuaded you to reject this fair and equitable settlement," Disney said. "Dear Walt," Sorrell retorted, "Willie Bioff is not our leader. Present your terms to OUR elected leaders, so that they may be presented to us and there should be no difficulty in quickly settling our differences." Eventually, the feds, in the person of the National Labor Relations Board, intervened. On July 29, after 62 days of rage on both sides, Disney settled – through clenched teeth. Disney and the Screen Cartoonists Guild squabbled intermittently until the end of the year, but Sorrell had won on the big points: better wages, job security and a "closed shop," which requires union membership as a condition for employment. Disney's revengeTo Disney, though, this wasn't just a dispute between management and labor. It was oedipal rebellion against the father in his own house. In October 1947, Disney got his chance for revenge when he testified before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, which was investigating Hollywood for alleged communist subversion in motion picture content and within the ranks of organized labor.  Disney was called as a friendly witness, and friendly he was: While waiting to testify, he good-naturedly sketched pictures of Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse for the children of the committee members. At the witness table, Disney emphasized that while today "everyone in my studio is 100% American," the percentage had not always been so high. He named the name that had stuck in his craw since 1941. "A delegation of my boys, my artists, came to me and told me that Mr. Herbert Sorrell … was trying to take them over," Disney said. Sorrell and his cohorts, charged Disney, "are communists," though admittedly, "no one has any way of proving those things." Proven or not, Disney's allegations were career-killers. Many of the activist cartoonists of 1941 fell victim to Hollywood's notorious blacklist era, when hundreds of workers on both sides of the screen were rendered persona non grata at the studios for their political affinities. As a result, the Screen Cartoonists Guild softened its tone. In 1952, it voted to become affiliated with the firmly anti-communist International Alliance of Theatrical and Stage Employees – Bioff's former outfit. As for Sorrell, he was hounded by charges of communist sympathies and ultimately barred from a leadership position in his own union. Disney, you know about. After venting before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, he navigated the company back to the 50-yard line of America's culture wars. There the entertainment conglomerate stayed – until recently, when it wandered off Disney World into the swampland of Florida politics. Thomas Doherty does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |

| ADHD in adults is challenging but highly treatable – a clinical psychologist explains Posted: 09 May 2022 05:04 AM PDT  When I was a child in the 1980s, the people I knew with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder were hyperactive boys who went to the school nurse at lunchtime to get their medicine. Many people assumed that these boys would "grow out of" their symptoms as teenagers or adults. For most of the 200-year-plus history of the condition we now know as ADHD, it was considered a childhood disorder. Specialists began to more widely recognize that ADHD can also affect adults only in the 1990s, when scientific evidence showed that some people continue to experience ADHD symptoms into adulthood and that it can profoundly effect their lives. In the past 30 years, adult ADHD has gone from barely recognized to a well-established disorder with evidence-based treatment options. In my 20 years studying and treating ADHD in adults, it's been exciting to witness and, in a small way, contribute to advances in evidence-based treatment for adult ADHD made by researchers around the world. Living with ADHDADHD is a disorder with symptoms of inattention such as distractibility and disorganization. It can also include hyperactivity and impulsivity in some but not all individuals. ADHD begins in childhood and causes problems in school, work and in social relationships. One study estimates that about 3.4% of adults worldwide meet criteria for ADHD, and recognition of ADHD in girls and women has increased in recent years. Symptoms of ADHD run in families and are linked to the functioning of specific brain regions. But the experience of ADHD isn't entirely based in genetics. A person's environment can influence how much ADHD causes problems in their daily life. Because ADHD symptoms overlap with those of other conditions such as depression and anxiety disorders, a careful, multistep professional evaluation is necessary to accurately diagnose it. There is no question that living with ADHD presents real and persistent challenges. But today adults with ADHD have greater access to information and more evidence-based treatment options. And there are scientifically supported reasons for optimism and hope about effective treatment for adult ADHD. To date, the main strategies for managing ADHD in adults are medication and a type of therapy called cognitive behavioral therapy for adult ADHD. Current evidence points to medicine as being more effective at reducing adult ADHD symptoms than therapy, but the research base for ADHD therapy is growing. And because they work in different ways, medication and therapy can be considered complementary tools in the adult ADHD toolbox. Medication optionsThe medications most commonly used to treat ADHD are called stimulants. It may seem strange that medications called stimulants are prescribed for a disorder that can involve hyperactivity. Stimulant medications for ADHD work by increasing the availability of the brain chemicals dopamine and norepinephrine in the regions of the brain associated with attention and self-regulation. Stimulant medications, when taken by mouth as prescribed, are relatively safe and unlikely to be addictive. The two main types of stimulant medications are methylphenidate, sold under brand names such as Ritalin and Concerta, and stimulants in the amphetamine family such as lisdexamphetamine, which go by the brand names Adderall and Vyvanse. Ritalin and Adderall are shorter-acting formulations – typically for around four to six hours – while Concerta and Vyvanse are designed to work up to about 12 hours. Common side effects from stimulants may include reduced appetite and weight loss, as well as headaches or sleep problems if taken too close to bedtime. In addition, people with cardiac problems may not be prescribed these medications because they can cause slightly elevated heart rate and blood pressure. Nonstimulant medications used to treat ADHD in adults include atomoxetine, which increases the brain neurotransmitter norepinephrine, and bupropion, an antidepressant drug sometimes used to treat ADHD that increases both dopamine and norepinephrine. A recent analysis found that all four of these medication types reduced ADHD symptoms better than a placebo, or "sugar pill," over about 12 weeks. Amphetamine-based medications worked the best overall for adults, and methylphenidate, bupropion and atomoxetine seemed to work slightly less well but with few differences among them. Unfortunately, very few studies have followed patients for longer periods of time, so it's unclear whether these positive results persist. Several studies using health care datasets offer intriguing information about the potential positive effects of medication for people in real-life settings. These studies found a relationship between prescriptions for ADHD medications and lower rates of depression, motor vehicle crashes, suicide-related events and negative events related to substance abuse. Although not definitive, this research points toward positive effects of ADHD medications beyond just reducing symptoms. Medications are not the right choice for everyone. Some people have unpleasant side effects or find that the medications are not effective. Because there is no way yet to predict which medication will work for which patient, adults with ADHD should be prepared to work closely with their doctor to try different medication types and doses to find the one that provides the right balance of positive effects with minimal side effects. The bottom line is that, although medications are not a perfect solution, medication is an important part of the treatment toolbox for many adults with ADHD. Specialized therapy for adult ADHDWhereas medications treat ADHD "from the inside out," specialized therapy for ADHD works "from the outside in" by helping clients learn skills and structure their environments to reduce the negative impact of ADHD on their lives. In cognitive behavioral therapy, clients work with a therapist to understand the interaction between their thoughts, feelings and actions and learn skills to cope with problems and meet important goals. There are different styles of cognitive behavioral therapy based on the problem that the client wants to work on. These treatments are evidence-based, while still tailored to each individual client. Over the past two decades, researchers have begun to develop and test cognitive behavioral therapies specifically for adults with ADHD. These specialized therapies help clients integrate organization and time-management skills into their lives. They also typically help people incorporate strategies to increase and maintain motivation to complete tasks and combat procrastination. Most cognitive behavioral therapies teach clients to become aware of the effects of their thought patterns on emotions and actions so that nonhelpful thoughts can have less influence. Whereas therapy for depression and anxiety tends to focus on overly negative thinking, ADHD therapy sometimes targets overly positive or overly optimistic thinking that can sometimes get clients in trouble. Reasons for optimismIn 2017, my students and I conducted a meta-analysis, a type of study that quantitatively summarizes the effects of multiple studies. Using data from 32 studies and up to 896 participants, we found that, on average, adults with ADHD who participated in cognitive behavioral therapy saw reductions in their ADHD symptoms and improvements in their functioning. However, the effects tended to be smaller than those observed with medication. Cognitive behavioral therapy seemed to have stronger effects on inattentive symptoms than on hyperactive-impulsive ones, and effects did not depend on whether participants were already taking medication. While cognitive behavioral therapy for adult ADHD appears to be a promising option for ADHD treatment, unfortunately, it can be difficult to find a therapist. Because therapy aimed at adult ADHD is relatively new, fewer clinicians have been trained in this approach. However, manuals for clinicians and workbooks for clients are available for those interested in this treatment option. And telehealth may make these treatments more accessible. And as has been the case for other forms of cognitive behavioral therapy, e-Health interventions like app-delivered therapy could bring treatment directly into the daily lives of people with ADHD. More targeted forms of ADHD therapy are on the horizon, including specific approaches for the needs of college students with ADHD. Laura E. Knouse is an unpaid clinical consultant for Get Inflow LTD. She is a member of the professional advisory board for Children and Adults with ADHD (CHADD). |

| Posted: 09 May 2022 05:03 AM PDT  Lawyers representing voters in Arizona, Georgia and North Carolina have filed lawsuits alleging that their elected congressional representatives are barred from running for future office based on a little-known provision of the 14th Amendment. Specifically, Section 3 of the 14th Amendment reads:

Proponents of barring these representatives from running for reelection argue that their active support for those who stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, qualifies as involvement in "insurrection or rebellion" against the U.S. government. As a constitutional scholar, I believe that the lawyers seeking disqualification have a steep hill to climb in all of these cases – especially when their arguments based on the 14th Amendment collide with the First Amendment and its protection of free speech. That is not stopping those who want to hold accountable the elected officials who were involved in the storming of the Capitol on Jan. 6. The challenges filed against GOP Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, Madison Cawthorn of North Carolina and Paul Gosar and Andy Biggs of Arizona – as well as Arizona Rep. Mark Finchem – are part of a larger national campaign run by the nonprofit advocacy groups Free Speech for People and Our Revolution. So far, judges have dismissed those arguments in Arizona and North Carolina. Both are on appeal. Greene's role in Jan. 6The case against Rep. Greene of Georgiaprovides a useful lens through which to analyze this unique constitutional claim. The challenge to her candidacy came to an end on May 5 when a Georgia state Judge Charles Beaudrot Jr. ruled that Greene should remain on the ballot because lawyers challenging Greene's run failed to prove that she engaged in insurrection on Jan. 6, 2021 "The evidence in this matter is insufficient to establish that Rep. Greene … 'engaged in insurrection or rebellion' under the 14th Amendment to the Constitution," Judge Charles Beaudrot wrote in his ruling. The lawsuit against Greene claimed, for example, that she frequently referred to the protest effort against the 2020 presidential election as "our 1776 moment." This reference, lawyers argued, is a clear allusion to – indeed, code for – a violent overthrow of the existing government. They claimed Greene had, at a minimum, given aid or comfort to enemies of the United States or, at most, engaged in insurrection by deploying such rhetoric. And, after her most recent court hearings on April 22, 2022, text messages surfaced in which she asked about the possibility of President Donald Trump's declaring martial law. In the text, which was uncovered by the House select committee investigating the events of Jan. 6, Greene told then-White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows that some members of Congress were saying in a private chat group that "the only way to save our Republic is for Trump to call for Marshall (sic) law. I don't know on those things. I just wanted you to tell him." Greene argued that her statements and social media posts encouraged lawful protest by those who believe that the 2020 election was stolen. The First Amendment, she argued, allows for a broad range of free and unfettered speech, particularly political speech. Greene also testified under oath that she had no knowledge that any protester intended to disrupt the joint session of Congress that had convened to count the electoral votes. In response to many of the questions posed to her, she claimed more than 50 times during her hearing that she didn't recall. Greene further testified that while she did encourage people to come to Washington, D.C., for a peaceful march, she did not assist any protester in navigating through the Capitol complex, as some have alleged. Forgiving rebel soldiersSection 3 of the 14th Amendment was passed shortly after the Civil War in 1866 to bar Confederates from federal government positions. But that ban didn't last long. A blanket amnesty for former Confederate soldiers was passed in 1872, making the vast majority of the rebels again eligible for office. In 1898, the prohibition was removed for the last few hundred former Southern congressmen and senators.  Cawthorn's attorney, James Bopp Jr., argued that the Amnesty Act of 1872 nullified Section 3 of the 14th Amendment and allows Cawthorn to seek election in the upcoming May 17, 2022, GOP primary. U.S. District Judge Richard Myers agreed and dismissed the case against Cawthorn. The district judge ruled that the Amnesty Act of 1872, which exempted Confederates from proscriptions of Section 3, is still in force and shields Cawthorn from being prevented to run for office. Unlike the case in North Carolina, the case against Greene in Georgia was allowed to proceed by a federal judge there. On April 18, 2022, U.S. District Judge Amy Totenberg denied Greene's motion to block the case against her and best summed up the constitutional morass the cases have raised. "This case," Totenberg wrote in her 73-page ruling, "involves a whirlpool of colliding constitutional interests of public import." Greene has appealed that decision. Protected free speechPolitical speech has – and deserves – special protection. To protest the government, even using strong, unpleasant or unpopular language, is central to the protections afforded by the First Amendment.  As such, courts tend to cast a wide net when defining speech covered by the First Amendment. In addition to the First Amendment limitations, I think there is something anti-democratic about prohibiting a candidate from even running for office. The notion that voters get to choose their elected representatives through free and fair elections represents a principle at the core of American democratic traditions. To remove the voters' ability to choose those whom they wish to elect to public office requires a weighty justification, and courts have long ruled this way. While aiding and abetting an insurrection is such a justification, it is an open question whether Greene's conduct fits within the definition of Section 3 of the 14th Amendment. Clearly, had Greene charged the Capitol with a weapon demanding that Congress seat President Trump, her actions would be clear and her disqualification warranted. But instead of weapons and storming, Greene deployed words and electronic posts. The distinction makes a difference. In my view, given the First Amendment's robust protection of speech, to bar a candidate from running for office requires evidence of intent to engage in insurrection in far greater proportion than what has thus far been presented in the case against Greene. Even Greene's call for martial law likely is not enough. Bizarre and wrongheaded statements are protected by the First Amendment just as cogent and thoughtful ones are. [Like what you've read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation's daily newsletter.] Ronald Sullivan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |

| Posted: 09 May 2022 05:03 AM PDT  There's a growing rift between corporate America and the GOP – two groups that have long been bedfellows. The latest incident involves Disney and its decision to speak out against a Florida law that prevents instruction of sexual orientation or gender identity from kindergarten through third grade. Republicans in the state, including the governor, reacted furiously, voting to strip Disney of the special tax and self-governing privileges it has held for 55 years. The spat follows rows between the GOP and corporate America over restrictive voting measures and bathroom bills. In 2021, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell bluntly warned companies to "stay out of politics" – though he later softened his tone. Meanwhile, Democrats are trying to capitalize on the fracture. As a management professor, I study how corporate executives' values and political views affect the decisions they make on behalf of their companies. While I believe CEOs are partly responsible for the growing business-GOP divide, it's not the only factor driving it. A tight relationship loosens upThe close relationship between corporate America and the Republican Party dates back to the 1970s. Companies provided financial support to conservative war chests and in return received business-friendly policies like reduced corporate taxes and regulations. The alliance has arguably been quite a success for Big Business. Corporate taxes as a share of U.S. gross domestic product are only about 1%, the lowest since the 1930s and down from 4.1% in 1967. But this union has become increasingly strained in recent years over a range of social issues, particularly regarding LGBTQ rights. For example, in 2015 many companies, including Apple and Walmart, denounced so-called religious freedom laws like one passed in Indiana that would allow businesses to discriminate against LGBTQ customers. The following year there was a similar corporate backlash over North Carolina's ban on transgender individuals' using public bathrooms. Boycotts by several companies, including PayPal and the NCAA, led to a partial repeal in 2017. Companies were also vocal during former President Donald Trump's presidency over such matters as his travel ban from Muslim-majority countries and his comments following the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. For some, it seemed the role he and other Republicans played in laying the ground for the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection at the Capitol may have been the last straw, as dozens of companies, including AT&T and Marriott, said they would cut off donations to the 147 Republicans who voted against certifying President Joe Biden's election. The push for more restrictive voter laws continues the battle over the election. Republicans in states across the country cite alleged fraud in the 2020 election – despite no evidence that any occurred – as the impetus behind their push. And as the Supreme Court weighs whether to overturn Roe v. Wade, the landmark ruling upholding women's right to an abortion, the issue is certain to drive more wedges between Republicans and companies, some of which have indicated they will support employees who wish to terminate a pregnancy. Why have companies become more outspoken in recent years and willing to upset an alliance that has helped them reduce their tax bills and regulatory hurdles? My research suggests there are three driving forces for this trend. CEOs doing 'what we think is right'The CEO is the corporation's top decider, which means his or her political leanings can filter into business decisions. And in recent years, CEOs of some of the largest U.S. companies have cited their own personal values as their reason for speaking out on social issues. As Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan told The Wall Street Journal in 2016, "Our jobs as CEOs now include driving what we think is right." In my own research, I've found a CEO's political affiliation can affect how a company spends money. CEOs who mostly donate to Democrats tend to spend more on their employees, community activities and environmental issues, regardless of their company's profitability. That is, they seem to believe it's simply the right thing to do. Republican CEOs, on the other hand, tend to tie spending on outside issues to financial performance, reflecting the notion that companies are responsible to shareholders first and foremost. More recent research also demonstrates that liberal executives tend to pay more attention to gender diversity inside their companies and are less likely to reduce their workforce when economic conditions deteriorate, consistent with the values that liberals prioritize. But relatively few CEOs are staunchly liberal, so the impact of the CEO on this trend may be limited. A recent study found that only about 18% of the more than 3,500 people who served as CEOs of companies in the Standard & Poor's 1500 from 2000 to 2017 donated primarily to Democratic candidates, while 58% gave mostly to Republicans. Growing worker activismEmployees also play an important role driving corporate activism. Recent management research shows that companies with more liberal employees spend more resources on improving gender and race diversity and sustainability issues. Similarly, a 2019 study found that companies are more likely to concede to activists' demands over issues like reducing carbon emissions and increasing front-line workers' pay when they have a more liberal workforce. Companies may be responding to research showing the benefits of listening to their employees and showing their voices matter. For example, workers tend to show more trust and commitment toward a company when they feel it shares their values, which leads to higher productivity. A 2017 survey found that 89% of employees said they'd accept a reduced salary to work at a company whose values match their own. Other research shows engagement in social activities like protecting the environment leads to less employee turnover. In my own research, which tracked companies' engagement on same-sex marriage issues in the 2000s and 2010s, I found that the likelihood of CEOs' speaking out on same-sex marriage significantly increased when there were more employees who donated to Democrats – which was true even when the CEO leaned conservative. Tracking popular opinionPublic opinion is another factor likely driving the growing rift with the GOP. Corporate executives tend to follow public sentiment, as they want to minimize the risk of losing customers for their products and services. The debate over same-sex marriage is a case in point. Public support for allowing gay people to marry surpassed 50% for the first time in 2011 – it's now at 70%. Until then, very few CEOs had made a public statement on the issue, according to my same-sex marriage research. Once popular opinion hit the halfway point, however, a lot more companies – including ones led by conservative CEOs – begin speaking out in favor of it. Interestingly, even liberal CEOs said very little until 2011, including those who already provided employees with domestic partner benefits. And more recently, it has become even more critical for companies to consider public sentiment when deciding whether to take a stand on a hot-button issue. That's because their younger customers, especially millennials, increasingly say CEOs have a responsibility to speak out and they would be more likely to buy products if they do. On the voting laws, a recent poll found that most people favor legislation that makes it easier to vote, not harder. Who's leaving whomBut corporate America isn't necessarily moving away from the Republican Party and toward the Democrats. Instead, businesses are trying to make clear that their concerns are not partisan in nature. The 100-plus companies that in 2021 signed a statement supporting voter rights and against bills that would restrict access emphasized this point. I believe a closer look at the three main factors – especially the role of workers and the public – behind the growth in corporate activism suggests something else. Companies aren't drifting away from the Grand Old Party. Rather, the GOP seems to be doing the drifting, not only from corporate America, but from the opinions of the American public as well – especially millennials. This is an updated version of an article published on April 22, 2021. M. K. Chin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Home – The Conversation. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

No comments:

Post a Comment