Home – The Conversation |

- Beyond NATO, new alliances could defend democracy and counter Putin

- Transgender youth on puberty blockers and gender-affirming hormones have lower rates of depression and suicidal thoughts, a new study finds

- A second look at the blue-eyes, brown-eyes experiment that taught third-graders about racism

- Can churches be protectors of public health?

- Russian invasion of Ukraine and resulting US sanctions threaten the future of the International Space Station

- How long does protective immunity against COVID-19 last after infection or vaccination? Two immunologists explain

- How a Black writer in 19th-century America used humor to combat white supremacy

- Digital sound archives can bring extinct birds (briefly) back to life

- International law says Putin's war against Ukraine is illegal. Does that matter?

| Beyond NATO, new alliances could defend democracy and counter Putin Posted: 25 Feb 2022 09:39 AM PST  Russian aggression toward Ukraine continues. The nations of the world, and their current alliances, have so far proved ineffective at curbing Russian President Vladimir Putin's ambitions. Right now at the United Nations, dictators and theocratic rulers get an equal voice with democratically elected governments. For almost anything urgent or relating to international security to get accomplished, Russia, China, the United Kingdom, France and the U.S. must all agree. Imagine the U.N. without them, and the NATO military alliance expanded across the globe, not dependent on one or two powerful nations to effectively prevent war and build democracy. How the global community responds to its new challenges may well decide the future of democracy and the cause of human rights in the 21st century. After years analyzing Putin's rise and the existential threat he poses, former Russian chess grandmaster and human rights advocate Garry Kasparov summed up the situation this way in late 2021: "We can either be the generation that renews democracy, or loses it forever." My research finds that new alliances may be needed to replace, or at least expand and support, the familiar ones built to keep global peace in the wake of World War II, when global politics were very different. That is why in my 2018 book, I suggested that the leading democratic nations all across the world join their economic, military, technological and moral power into "A League of Democracies." This concept built on ideas from U.S. Sen. John McCain and others such as foreign policy experts Ivo Daalder and James Lindsay. Developed democracies could work together to effectively counter not only the influence of Russia and China, but also creeping despotism and mass atrocities. This group could discourage military coups, support protest movements demanding democratic rights, prevent new arms races and help developing democracies strengthen their civil services. Beyond my own proposal, below are three promising new ideas for alliances that have recently emerged to meet the growing power of dictatorships. Imagine, for instance, that more than 40 democratic countries with more than 70% of the world's economic activity issued a total trade blockade of Russia after Putin invaded Ukraine. Copenhagen CharterThe Copenhagen Charter was created in 2018 by the Alliance of Democracies Foundation, a nonprofit founded by former Prime Minister of Denmark and NATO Secretary-General Anders Fogh Rasmussen. It is not yet a formal international treaty, but the goal is to create a powerful economic alliance similar to the military alliance that is NATO. Its members would coordinate international sanctions and aid, using their trade and financial power in the global economy. For instance, its members could collectively respond with tariffs or boycotts if Russia became too dominant in supplying natural gas to Europe, or if China tried to silence Australian critics by cutting off its imports from Australia. Coalition for a World Security CommunityAlso founded in 2018, the Coalition for a World Security Community proposes a global military alliance to protect democratic nations from autocratic forces. It would include Asian democracies like South Korea, Australia and India that are not yet part of any major multinational security agreements. One step in this direction is the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue between the U.S., Japan, India and South Korea. It was established in 2007 by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in response to China's economic and military rise, and could help deter a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. An Alliance of Free NationsThe Copenhagen Charter and the World Security Community ideas have been combined by political scientists Ash Jain and Matthew Kroenig at the Atlantic Council, a nonprofit policy think tank in Washington. They propose extending mutual protection among democracies through an "Alliance of Free Nations." This group would be a formal institution linking Western democracies with democratic allies in South America and Asia. It would replace temporary coalitions that gather only to deal with a single crisis, such as the Western nations that tried to negotiate with Putin before his invasion of Ukraine. Jain and Kroenig suggest starting this alliance by adding to the seven major industrialized democracies, who now meet as the Group of Seven, often called the "G-7." Adding South Korea, India and Australia could turn this group into a "Democratic 10," perhaps with the Philippines and Brazil as guests or observers at meetings. Ultimately, this group would be open to all the nations who support key democratic principles, like basic human rights, independent courts and free multi-party elections. U.S. President Joe Biden's Summit for Democracy in December 2021 invited those nations and others to support democratic systems around the world. A second summit is expected in late 2022. [More than 150,000 readers get one of The Conversation's informative newsletters. Join the list today.] I am on the board of the World Security Community, which is mentioned, but this is not a paid position. Other than that, I do a little TV interviewing, but my only paid employment is with Fordham. |

| Posted: 25 Feb 2022 08:02 AM PST  Recent studies estimate that 1.8% to 2.7% – or approximately 750,000 to 1.1 million – adolescents in the U.S. identify as transgender or nonbinary. Many of these trans youth experience high levels of negative mental health symptoms due to anti-transgender stigma, discrimination and lack of family or peer support. A 2021 study found that as much as 72% of trans youth were depressed, and half had seriously considered suicide. We are an epidemiologist and fourth-year medical student who study ways to make clinical care more inclusive for trans and nonbinary people. We conducted a study in collaboration with the Seattle Children's Hospital Gender Clinic that found that transgender youth on puberty blockers and gender-affirming hormone therapy are less likely to report depression and suicidal thoughts. Safe and proven treatmentsPuberty blockers are medications that delay puberty. By temporarily stopping the body from making the hormones that lead to puberty-related changes, young people and their families are given time to pause and make health decisions. These medications have been used for over 30 years to treat young people with puberty that starts too early, also called precocious puberty. Gender-affirming hormone therapy, like testosterone or estrogen, are medications that allow trans youth to experience a puberty appropriately aligned with their gender. There is no shortage of scientific and clinical societies that have found these medications to be both safe and effective for transgender people. Numerous medical and professional societies, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and the American Medical Association, endorse access to gender-affirming care specifically for trans youth. Social support, as well as access to gender-affirming care, is known to significantly reduce poor mental health in trans youth. In addition, several recent studies have suggested that early access to puberty blockers and hormones during adolescence can have long-term positive effects that last into adulthood. Despite these benefits, many young people face significant barriers in accessing gender-affirming care. Only 1 in 5 youth who need hormones have been able to access them.  To further examine the mental health effects of puberty blockers and hormone therapy, we followed 104 trans and nonbinary youth ages 13 to 20 during their first year of gender-affirming care. After one year, we found that young people who began puberty blockers or gender-affirming hormones were 60% less likely to be depressed and 73% less likely to have thoughts about self-harm or suicide compared to youth who hadn't started these medications. In addition, young people who were unable to start these medications within three to six months of their first appointment with a medical provider had a two- to threefold increase in depression and suicidal thoughts. Our findings suggest that delays in prescribing hormones and puberty blockers may worsen mental health symptoms for trans youth. What this means for anti-transgender legislation2021 and 2022 have been record-breaking years for anti-transgender legislation, including attempts to criminalize gender-affirming care for trans youth. [Over 140,000 readers rely on The Conversation's newsletters to understand the world. Sign up today.] Banning gender-affirming care will have immediate and long-term negative effects on the well-being of trans youth and their families, both by increasing the stigma and discrimination these young people face and by denying them access to critical life-saving and evidence-based health care. Our study builds on existing scientific evidence and underscores that timely access to gender-affirming care saves trans youth lives. Diana Tordoff receives funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health, the American Sexually Transmitted Diseases Association (ASTDA), and the Northwest Center for Public Health Practice at the University of Washington's School of Public Health. Arin Collin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |

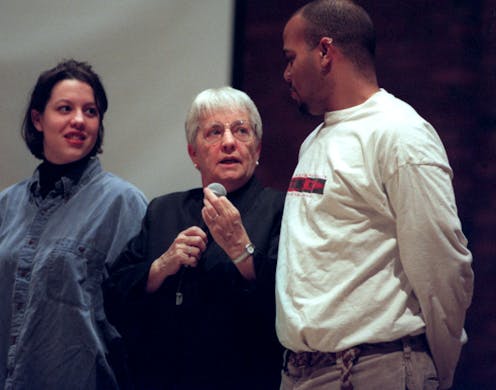

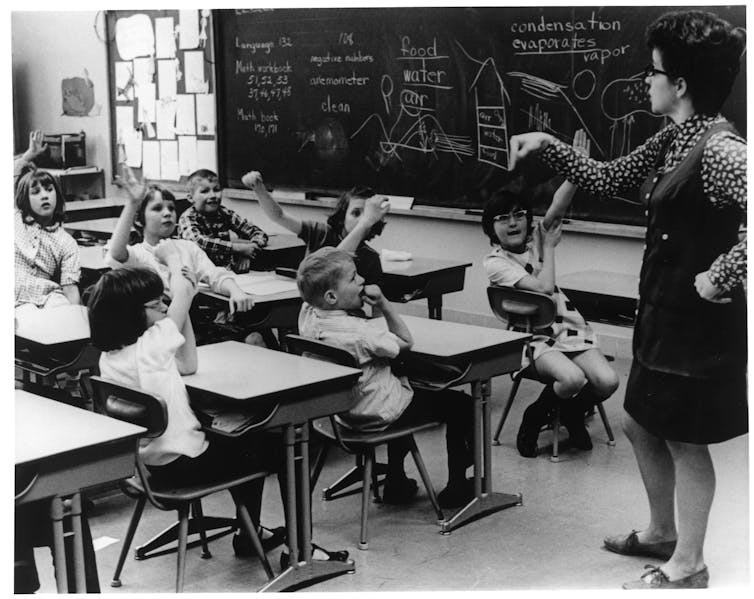

| A second look at the blue-eyes, brown-eyes experiment that taught third-graders about racism Posted: 25 Feb 2022 05:46 AM PST  The killing of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, was a seismic event, a turning point that compelled many Americans to do something and do it with urgency. Many educators responded by holding mandatory workshops on institutional racism and implicit bias, reforming teaching methods and lesson plans and searching for ways to amplify undersung voices. As a journalism professor and author of a book on race that spans more than 50 years, I've watched these developments with great concern. We've been here before, with unsettling and disturbing results. The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 was also an event that spurred educators to action, motivating one teacher to try out a bold experiment touted to reduce racism. The experiment took the nation by storm. The day after King's murder, Jane Elliott, a white third-grade teacher in rural Riceville, Iowa, sought to make her students feel the brutality of racism. Elliott separated her all-white class of students into two groups: blue-eyed children and brown-eyed children. On the first day, the blue-eyed students were informed that they were genetically inferior to the brown-eyed students. Elliott instructed the blue-eyed kids not to play on the jungle gym or swings. They wouldn't be allowed second helpings for lunch. They'd have to use paper cups if they drank from the water fountain.  The blue-eyed children were told not to do their homework because, even if they answered all the questions, they'd probably forget to bring the assignment back to class. That's just the way blue-eyed kids were, Elliott told the students. On the second day of the experiment, Elliott switched the children's roles. After the local newspaper published a story on Elliott and the experiment, she was flown to New York to appear on May 31, 1968, on "The Tonight Show" with Johnny Carson, where she extolled the experiment's effectiveness in cluing in her 8-year-old white students on what it was like to be Black in America.  A darker sideBut Elliott's experiment had a more sinister impact. To most people, it seemed to suggest that racism could be reduced, even eliminated, by a one- or two-day exercise. It seemed to evince that all white people had to do to learn about racism was restrain themselves from an impulse to engage in made-up cruelty. They needed not acknowledge their privilege or reflect on it. They didn't need to engage with a single Black person. But in reality, I found in researching for my book "Blue Eyes, Brown Eyes" that the experiment was a sadistic exhibition of power and authority – levers controlled by Elliott. Stripping away the veneer of the experiment, what was left had nothing to do with race. It was about cruelty and shaming. Subsequent research designed to gauge the efficacy of Elliott's attempt at reducing prejudice showed that many participants were shocked by the experiment, but it did nothing to address or explain the root causes of racism. The roots of racism – and why it continues unabated in America and other nations – are complicated and gnarled. They are steeped in centuries of economic deprivation and cultural appropriation. The nonstop parade of sickening events such as the murder of George Floyd surely is not going to be abated by a quickie experiment led by a white person for the alleged benefit of other whites – as was the case with the blue-eyed, brown eyed experiment. Sought-after diversity trainerNevertheless, Elliott became as famous as a teacher could become in America. The 1970s and 1980s were ripe for diversity education in the private and public sectors, and Elliott would try out the experiment at workshops on tens of thousands of participants, not just in the U.S. and Canada, but in Europe, the Middle East and Australia. She traveled to corporations, banks, prisons, schools and military bases. Thousands of educators across the United States folded the experiment into their curriculums. She was a standing-room-only speaker at hundreds of colleges and universities. She appeared on "The Oprah Winfrey Show" five times. Unsettling insultsElliott turned into America's mother of diversity training. The anti-racism sessions Elliott led were intense. To get her points across, Elliott hurled insults at workshop participants, particularly those who were white and had blue eyes. For many, the experiment went horribly awry. In doing the research for my book with scores of peoples who were participants in the experiment, I reached out to Elliott. At first, she cooperated with me. But when she discovered that I was asking pointed questions of scores of her former students, as well as others subjected to the experiment, she made an about-face and said she no longer would cooperate with me. She has since refused to answer any of my inquiries.  Scores of others did participate. I interviewed Julie Pasicznyk, who had been working for US West, a giant telecommunications company in Minneapolis. She was hesitant to enroll in Elliott's workshop but was told that if she wanted to succeed as a manager, she'd have to attend. Pasicznyk joined 75 other employees for a training session in the company's suburban Denver headquarters in the late 1980s. "Right off the bat, she picked me out of the room and called me 'Barbie,'" Pasicznyk told me. "That's how it started, and that's how it went all day long. She had never met me, and she accused me in front of everyone of using my sexuality to get ahead." "Barbie" had to have a Ken, so Elliott picked from the audience a tall, handsome man and accused him of doing the same things with his female subordinates, Pasicznyk said. Elliott went after "Ken" and "Barbie" all day long, drilling, accusing, ridiculing them, to make the point that whites make baseless judgments about Blacks all the time, Pasicznyk said. Elliott championed the experiment as an "inoculation against racism." [The Conversation's Politics + Society editors pick need-to-know stories. Sign up for Politics Weekly.] Questioning authorityThe mainstream media were complicit in advancing such a simplistic narrative. They embraced the experiment's reductive message, as well as its promised potential, thereby keeping the implausible rationale of Elliott's crusade alive and well for decades, however flawed and racist it really was. Perhaps because the outcome seemed so optimistic and comforting, coverage of Elliott and the experiment's alleged curative powers cropped up everywhere. Elliott was featured on nearly every national news show in America for decades.  Elliott's bullying rejoinder to any nonbeliever was to say that however much pain a white person felt after one or two days of made-up discrimination was nothing when compared to what Blacks endure daily. Back when she introduced the experiment to her Iowa students more than five decades ago, at least one student had the audacity to challenge Elliott's premise, according to those who were in the classroom at the time. When she separated the class by eye color and announced that blue-eyed children were superior, Paul Bodensteiner objected at every turn. "It's not true!" he challenged. Undeterred, Elliott tried to appeal to Paul's self-interest. "You should be happy! You have the right color eyes!" But Paul, one of eight siblings and the son of a dairy farmer, didn't buy Elliott's mollification. "It's not true and it's not fair no matter what you say!" he responded. I often think about Paul Bodensteiner. How can we teach kids to be more like him? Is it even possible today? Stephen G. Bloom does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |

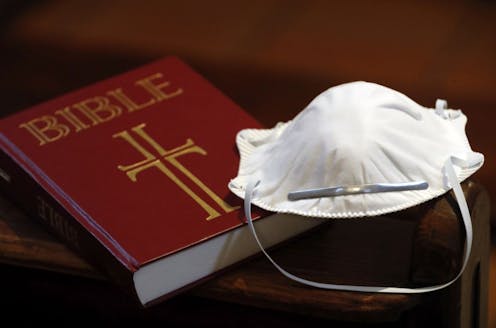

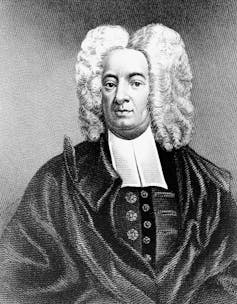

| Can churches be protectors of public health? Posted: 25 Feb 2022 05:46 AM PST  Over the past two years of living with COVID-19, many churches have had to think in new ways. Congregations across the country are experimenting with practices such as virtual worship and Bible study or masking and social distancing – even as others go "back to normal." While scholars have studied the relationship between religion and health for decades, the pandemic has put a spotlight on it. Often, this attention emphasizes examples of churches opposing safety recommendations, such as vaccines or lockdowns, but this misses the complexity and variety of religious responses to public health problems. As a scholar of Christianity in the United States, I believe understanding how churches have navigated health crises in the past can help us better understand our present. Over the past two years, I have worked with an interdisciplinary team of researchers based at the Hartford Institute for Religion Research to understand how churches are confronting the realities of COVID-19. U.S. history, coupled with our survey of congregations, suggests that a commitment to public health has long been a part of ministry, but there is room to make it stronger. A history of protecting healthChristian leaders have been advocating for public health in the United States since the Colonial period. Historian Philippa Koch has argued that the religious worldview of American Protestants in the 18th century helped them "accept the new promises and insights of modern medicine." According to Koch, this unwavering faith in God's plan for creation helped spur individuals like the Puritan minister Cotton Mather to promote inoculation for smallpox as a gift from God.  During the 1918 influenza pandemic, too, congregations were on the front lines of public health. Churches in North Carolina, for example, sought to make sure their worship space was "well ventilated" to avoid spreading the virus. They also required members to wear "germ proof" gauze masks. Churches in Washington state prohibited public singing and roped off pews to ensure that congregants would be spread out around the sanctuary. Many churches also canceled in-person worship gatherings and turned to the technology of the day: newspapers. In Los Angeles, ministers encouraged their congregants to "go to church in your own home today" with sermons printed in the paper. In Indianapolis, the newspaper printed an order of worship with hymns, Scripture and prayers. The paper also included sermons from local congregations, including Episcopalian, Catholic, Baptist and Jewish. Presbyterian minister Francis Grimke later reflected on his church's decision to close, stating, "If avoiding crowds lessens the danger of being infected, it was wise to take the precaution and not needlessly run in danger and expect God to protect us." Not all churches responded to the health precautions with enthusiasm. Many ministers insisted that communal prayers were necessary to get the country through the sickness. Others blatantly disobeyed public health orders. In Harrison, Ohio, the Rev. George Cocks of Trinity Methodist Church and 16 members of his congregation were arrested and jailed for a staged protest. After being locked up, he preached through the window of his jail cell to approximately 500 individuals who had gathered to hear him. Over the past few decades, more recent church practices that intersect with health include holding blood drives, hosting 12-step programs for addiction, running soup kitchens and providing basic mental health counseling. Churches and COVID-19The past two years have been difficult on churches. Our team at the Exploring the Pandemic Impact on Congregations project surveyed more than 2,000 churches and found that the vast majority – 83% of those surveyed – reported that a member had tested positive for the virus. Thirty-seven percent had a staff member who had tested positive. While our data shows that nearly all churches in the United States have been affected by COVID-19, not all of them have responded to the pandemic in the same way. Political polarization around public health measures has only complicated how congregations have responded to COVID-19. Twenty-eight percent of the 2,074 churches we surveyed invited a medical professional to speak to their membership about the pandemic. Evangelical Christian Francis Collins – who recently stepped down as director of the National Institutes of Health and is now acting science adviser to President Joe Biden – has modeled how the science of public health can be framed in religious terms, such as loving one's neighbor. Just 8% of churches volunteered to serve as a testing or vaccination location. These churches were more likely to have more than 250 members, have been founded recently, and be racially diverse.  Before the pandemic, many clergy had a positive attitude toward vaccinations but did not see them as particularly relevant to their faith communities. There is reason to believe that this is changing. Our survey found the majority of clergy across the country, 62%, have encouraged their congregants to be vaccinated against COVID-19. This varies significantly across different segments of Christianity in the U.S., however. Of clergy surveyed from historically Black denominations, 100% had encouraged their congregations to get vaccinated. Over three-quarters of mainline Protestant congregations and nearly two-thirds of Latino churches had clergy publicly encouraging members to take the vaccine. Half of Roman Catholic and Orthodox clergy advocated for their congregants to take the vaccine, and among white Evangelicals, only 29% of clergy offered similar advice. [More than 150,000 readers get one of The Conversation's informative newsletters. Join the list today.] Among churches with a senior woman clergy leader, 82% encouraged their members to get vaccinated, as compared with 58% of those with senior male leaders. Small churches were also more likely to recommend the vaccine to their congregants. Our project has also conducted a survey on how churches have adapted social outreach programs during COVID-19 and is currently fielding a survey about the pandemic's effect on Christian education. Given the results of our first survey, there is significant room for U.S. congregations to think more deeply about how their work intersects with public health. But before taxing clergy with something else to add to their already overburdened schedules, we believe it's worth encouraging congregational leaders to consider their churches as institutions of public health: places that can promote the physical, spiritual and emotional health of both their members and the local community. Andrew Gardner does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |

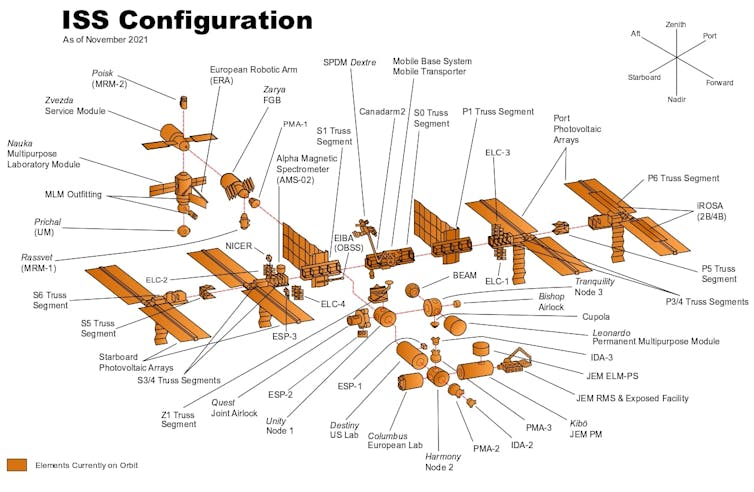

| Posted: 25 Feb 2022 05:46 AM PST  New U.S. sanctions on Russia will encompass Russia's space agency, Roscosmos, according to a speech U.S. President Joe Biden gave on Feb. 24, 2022. In response to these sanctions, the head of Roscosmos on the same day posted a tweet saying, among other things, "If you block cooperation with us, who will save the ISS from an uncontrolled deorbit and fall into the United States or Europe?" The International Space Station has often stayed above the fray of geopolitics. That position is under threat. Built and run by the U.S., Russia, Europe, Japan and Canada, the ISS has shown how countries can cooperate on major projects in space. The station has been continuously occupied for over 20 years and has hosted more than 250 people from 19 countries. As a space policy expert, the ISS represents, to me, a high point of cooperation in space exploration. But for the current crew of two Russians, four Americans and one German, things may be getting worrisome as tensions rise between the U.S. and Russia. Several agreements and systems are in place to make sure that the space station can function smoothly while being run by five different space agencies. As of Feb. 24, there were no announcements of unusual actions aboard the station despite the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine. But the Russian government has brought the ISS into geopolitics before and is doing so again. Managing the ISSWhat came to be known as the International Space Station was first conceived on NASA drawing boards in the early 1980s. As costs rose past initial estimates, NASA officials invited international partners from the European Space Agency, Canada and Japan to join the project. When the Soviet Union collapsed at the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, the Russian space program found itself in dire straits, suffering from lack of funding and an exodus of engineers and program officials. To take advantage of Russian expertise in space stations and foster post-Cold War cooperation, the NASA administrator at the time, Dan Goldin, convinced the Clinton administration to bring Russia into the program that was rechristened the International Space Station. By 1998, just prior to the launch of the first modules, Russia, the U.S. and the other international partners of the ISS entered into memorandums of understanding that spelled out how major decisions would be made and what kind of control each nation would have over various parts of the station. The body that governs the operation of the space station is the Multilateral Coordination Board. This board has representatives from each of the space agencies involved in the ISS and is chaired by the U.S. The board operates by consensus in making decisions on things like a code of conduct for ISS crews. Even among international partners who want to work together, consensus is not always possible. If this happens, either the chair of the board can make decisions on how to move forward or the issue can be elevated to the NASA administrator and the head of the Russian space agency, Roscosmos.  Territories in spaceWhile the overall operations of the station are run by the Multilateral Coordination Board, things are more complicated when it comes to the modules themselves. The International Space Station is made of 16 different segments constructed by different countries, including the U.S., Russia, Japan, Italy and the European Space Agency. Under the ISS agreements, each country maintains control over how its modules are used. This includes the Russian Zarya, which provides electricity and propulsion to the station, and Zvezda, which provides all of the station's life support systems like oxygen production and water recycling. The result is that ISS modules are treated legally as if they are territorial extensions of their countries of origin. While all crew onboard can theoretically be in and use any of the modules, how they are used must be approved by each country.  International tensions and the ISSWhile the ISS has functioned under this structure remarkably well since its launch more than 20 years ago, there have been some disputes. When Russian forces annexed the Ukrainian territory of Crimea in 2014, the U.S. imposed economic sanctions on Russia. As a result, Russian officials announced that they would no longer launch U.S. astronauts to and from the space station beginning in 2020. Since NASA had retired the space shuttle in 2011, the U.S. was entirely dependent on Russian rockets to get astronauts to and from the ISS, and this threat could have meant the end of the American presence aboard the space station entirely. While Russia did not follow through on its threat and continued to transport U.S. astronauts, the threat needed to be taken seriously. The situation today is quite different. The U.S. has been relying on private SpaceX rockets to transport astronauts to and from the ISS. This makes potential Russian threats to launch access less meaningful. But the invasion of Ukraine does seem to have upped the intensity of geopolitical maneuvering involving the ISS. The new U.S. sanctions are designed to "degrade their aerospace industry, including their space program." The tweet in response from Dmitry Rogozin, the head of Roscosmos, "explained" that Russian modules are key to moving the station when it needs to dodge space junk or adjust its orbit. He went on to say that Russia could either refuse to move the station when needed or even crash it into the U.S., Europe, India or China. Though dramatic, this is likely an idle threat due to both political consequences and the practical difficulty of getting Russian cosmonauts off the ISS safely. But I am concerned about how the invasion will affect the remaining years of the space station. In December 2021, the U.S. announced its intention to extend operation of ISS operations from its planned end date of 2024 to 2030. Most ISS partners expressed support for the plan, but Russia will also need to agree to keep the ISS operating beyond 2024. Without Russia's support, the station – and all of its scientific and cooperative achievements – may face an early end. The ISS has served as a prime example for how nations can cooperate with one another in an endeavor that has been relatively free from politics. Increasing tensions, threats and more aggressive Russian actions – including its recent test of anti-satellite weapons – are straining the realities of international cooperation in space going forward. Wendy Whitman Cobb is affiliated with the US Air Force School of Advanced Air and Space Studies. Her views are her own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Defense or any of its components. |

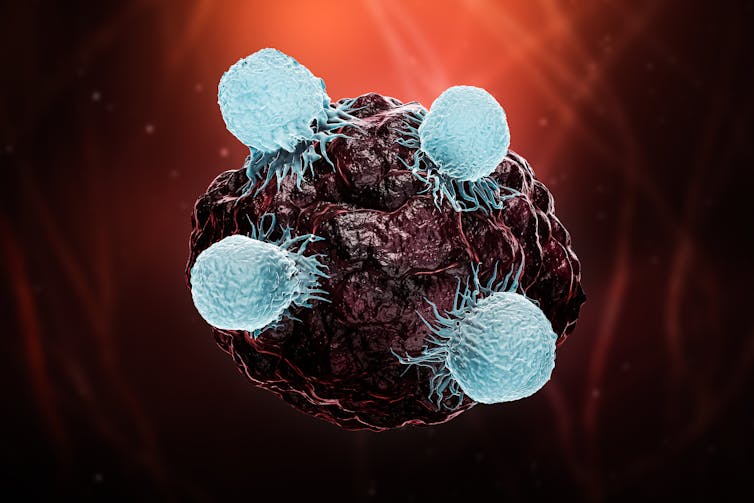

| Posted: 25 Feb 2022 05:45 AM PST  As the omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 took hold across the globe in late 2021, it became readily apparent that the pandemic had entered a new phase. Having experienced a previous COVID-19 infection or being vaccinated still left many people wondering how vulnerable they were to the virus. Some 4.9 billion people – or 63.9% of the world's population – have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine as of late February 2022. And more than 430 million cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed since the start of the pandemic. So with the majority of the world population being either immunized against COVID-19 or having recovered from infection, people have rightly begun to ask: How long will the immunity triggered by either vaccination, an active infection or a combination of both provide immune protection? This is a challenging question because the virus is relatively new and novel variants have continuously emerged. However, researchers are beginning to better understand how existing immunity protects against reinfection and the prevention of severe COVID-19 that can lead to hospitalization and death. As immunologists studying inflammatory and infectious diseases, including COVID-19, we are interested in understanding the nature of such protective immunity. The role of antibodies and 'killer' T cellsUpon vaccination or infection with COVID-19, your body produces two types of protective immune responses. The first type involves B cells, which produce antibodies. Antibodies are Y-shaped proteins that form the first line of defense against an infection or perceived invader, such as a vaccine. Much like a lock and key, antibodies can directly bind to a virus – or to the spike protein of COVID-19, in the case of the mRNA vaccines – and prevent it from gaining entry into cells. However, once a virus successfully enters the cells, antibodies are no longer effective. The virus begins replicating in the infected cells and spreading to other cells. This is when the immune system calls into action another type of immune cell known as killer T cells, which act as the second line of defense. Unlike antibodies, killer T cells cannot directly "see" the virus and thus cannot prevent a virus from entering cells. However, the killer T cells can recognize a virus-infected cell and immediately destroy the cell before the virus gets a chance to replicate. In this way, killer T cells can help prevent a virus from multiplying and spreading. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the public has widely and mistakenly believed that antibodies provide the bulk of protective immunity, while not recognizing the important role of killer T cells. This is in part because antibodies are easy to detect, whereas killer T-cell detection is complex and involves advanced technology. When antibodies fail, it is the killer T cells that are responsible for preventing the more severe outcomes of COVID-19, such as hospitalization and death.  Memory is key to long-term protective immunityThen come the real veterans of the immune system, which can provide long-lived and strong immunity against an infection based on their past experience. After performing their tasks of clearing the infection or the spike protein of the virus, the antibody-producing B cells and killer T cells get converted into what are called memory cells. When these cells encounter the same protein from the virus, they recognize the threat immediately and mount a robust response that helps prevent an infection. This explains why multiple doses of COVID-19 vaccines that increase the number of memory B cells prevent reinfection – or breakthrough infections – better when compared with a single dose. And a similar increase in memory killer T cells prevents severe disease and hospitalization. Memory cells can remain in the immune system for long periods – sometimes even up to 75 years. This explains why people develop lifelong protective immunity in certain cases, such as after measles vaccination or smallpox infection. The trick, however, is that memory cells are highly specific. If new strains or variants of a virus emerge, as has been the case numerous times during the COVID-19 pandemic, memory cells may not be as effective. This raises the question: When do these different key players of the immune system emerge after infection, and how long do they last? Duration and longevity of immunity against COVID-19Antibodies begin mobilizing within the first few days following an infection with COVID-19 or after receiving the vaccine. They steadily increase in concentration for weeks and months thereafter. So by three months following infection, people have a robust antibody response. This is why the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has long held that people who have had a confirmed COVID-19 infection in the past 90 days do not need to quarantine when they come into contact with someone with COVID-19. But by about six months, antibodies start declining. This is what led to the so-called "waning immunity" that researchers observed in the fall of 2021, months after many people had been fully vaccinated. However, immunity is far more complex and nuanced, and antibodies only tell part of the story. Some B cells are long-lived, and they continue to produce antibodies against a virus. For this reason, antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 have been detected even a year after an infection. Similarly, memory B cells can be detected for at least eight months, and memory killer T cells have been observed for close to two years following COVID-19 infection. In general, vaccines have also been shown to trigger an immune memory similar to that of natural infection. However, long-term studies of the comparison do not yet exist. Nonetheless, a recent study that is not yet peer-reviewed showed that a third dose of vaccine increases memory B cell diversity, which leads to better protection even against variants like omicron. But the mere detection of an immune response does not translate to full protection against COVID-19. Based on the limited amount of time and research that researchers like us have been able to study COVID-19, it is difficult to precisely correlate the levels of antibodies and killer T cells with the degree of protection they offer. So while it is becoming clear that some form of immune response against the virus can be detected for more than a year after COVID-19 infection, their levels may not be enough to provide full protection against reinfection. Immunity from vaccination versus infectionOne recent study from the U.K. Health Security Agency showed that protection against infection from two doses of vaccine may last for up to six months. Similarly, another study showed that the mRNA vaccines were highly protective at two months, but that their effectiveness decreased by seven months – in part due to the emergence of the delta variant. In both studies, the vaccines were found to be better at preventing hospitalization and death than in preventing infection over time. [Research into coronavirus and other news from science Subscribe to The Conversation's new science newsletter.] There are contradictory reports on whether the protective immunity triggered following an active infection is better than that induced by the current vaccines. This may have resulted from the emergence of different variants of the virus during the study. However, the broad consensus is that COVID-19 infection can give rise to protection comparable to that from the vaccines, as shown in a recent study that has not yet been peer-reviewed. Hybrid immunityResearchers have also found that the protective immunity acquired from the combination of a COVID-19 infection followed by vaccination – called hybrid immunity – is very potent and remains effective for more than a year after infection with COVID-19. Interestingly, hybrid immunity triggers a very strong antibody response over an extended period. Such studies show how important it is for even people who have been previously infected with COVID-19 to get vaccinated to ensure the most robust protection against COVID-19. With the growing knowledge that both vaccines and active infections can trigger a strong and sustained killer T cell response that protects against hospitalization and death, immunologists are now researching how to develop vaccines that can trigger a similar sustained long-term antibody response to prevent reinfections. Hybrid immunity from those who are vaccinated and have experienced COVID-19 infection may offer some useful clues. Prakash Nagarkatti receives funding from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation Mitzi Nagarkatti receives funding from the National Institutes of Health. |

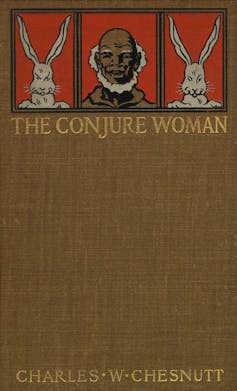

| How a Black writer in 19th-century America used humor to combat white supremacy Posted: 25 Feb 2022 05:45 AM PST  Any writer has to struggle with the dilemma of staying true to their vision or giving editors and readers what they want. A number of factors might influence the latter: the market, trends and sensibilities. But in the decades after the Civil War, Black writers looking to faithfully depict the horrors of slavery had to contend with readers whose worldviews were colored by racism, as well as an entire swath of the country eager to paper over the past. Charles Chesnutt was one of those writers. Forced to work with skeptical editors and within the confines of popular forms, Chesnutt nonetheless worked to shine a light on the legacy of slavery. His 1899 collection of stories, "The Conjure Woman," took place on a Southern plantation and sold well. At first glance, the stories seemed to mimic other books set in the South written in a style called "local color," which focuses on regional characters, dialects and customs. But Chesnutt had actually written a subversive counternarrative, using humor to poke holes in the nostalgic myths of the South and expose the contradictions of a racist society. Rewriting the pastAfter the Civil War, there was a concerted effort to portray the South as a pastoral place possessed with a culture of honor. Slavery, meanwhile, had been a nurturing, even benevolent, institution. These beliefs bled into the era's fiction, with white authors such as Thomas Nelson Page and Joel Chandler Harris writing stories that sentimentalized and softened the complex histories of the past.  Many of these stories feature a formerly enslaved older male who's given the affectionate moniker "Uncle." These characters tended to describe the Civil War as an affront on the Southern way of life, while presenting the South and its landed gentry as heroic. In "A Story of the War," for example, Harris introduces the character Uncle Remus, who recounts the time his master went away to fight the Civil War. Overcome with concern for the man who enslaved him, Uncle Remus follows him and witnesses a Northern soldier preparing to shoot him. In a moment of panic, Remus shoots the Northerner, wounding him. "A Story of the War," like most Southern local color tales, appealed to readers invested in the Lost Cause of the Old South, a revisionist ideology that depicts the creation of the Confederate States and cause of the Civil War as just and heroic. Historian Fred Bailey notes that stories like Page's and Harris' were "hailed by the South's upper-classes," while associations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy routinely read from these works at their meetings. Chesnutt's revisionist humorAt first glance, it would seem Chesnutt, who was mixed-race and could have easily passed for white, was merely working within the dominant literary form of his time and fashioning stories geared to a white audience. Like his white contemporaries, Chesnutt, in "The Conjure Woman," includes a character who's an "uncle" living on the abandoned plantation where he once toiled. But Chesnutt, as literary historian Dickson Bruce points out in his 2005 essay "Confronting the Crisis: African American Narratives," used the setting of the plantation to present a more authentic representation of slavery.  Uncle Julius, who appears in each of the collection's stories, isn't nostalgic for some bygone era. Instead, he reflects on his own life and seeks to show the humanity of the enslaved. He uses his ability as a raconteur to cleverly swindle a white carpetbagger who bought the plantation Julius lived on during his bondage and after the Civil War. The stories are descriptive, corrective – and, most importantly, funny. While Chesnutt's tales explicitly engage with the hard history of slavery, each of the stories ends on a lighter note, with Uncle Julius often getting what he wants. Throughout the collection, he parodies the conventions of Southern fiction – whether refuting racist tropes or showing the cruelty of the ruling class – subtly poking fun at a culture enveloped by the fog of nostalgia. Bound by formAt the same time, Chesnutt felt as if he couldn't simply write broadsides against myths like the Lost Cause. In order to be published, Black writers needed to appeal to the sensibilities of white readers and the demands of editors. For example, Uncle Julius spoke in a Black dialect that sounded similar to those of the uncles authored by white writers. This didn't come easily for Chesnutt. In one letter to his editor, Chesnutt described writing in this dialect as a "despairing task." Nonetheless, he avoided completely pandering to mainstream expectations of how Black characters should be portrayed. He rejected the emergent historiography of Reconstruction that refused to recognize the agency of African Americans, and despite working within the form, Chesnutt didn't present Julius as a buffoon who was happy to serve the whites in his midst. Even though his stories didn't overtly denounce racism, Chesnutt hoped they might still chip away at prejudice:

Humor opens doorsChesnutt is far from the only Black artist asked to make compromises. Poet Langston Hughes had a falling out with his patron, Charlotte Osgood Mason, who viewed African Americans as a link to the species' primitive past and wanted his work to be devoid of political progressivism. As Hughes wrote in his 1940 autobiography, "The Big Sea," "I was only an American Negro – who had loved the surface of Africa and the rhythms of Africa – but I was not Africa. I was Chicago and Kansas City and Broadway and Harlem. And I was not what she wanted me to be." In Chesnutt, I also see ties to contemporary Black comedians who center their humor around race. During the third season of "Chappelle's Show," Dave Chappelle famously suffered from an existential crisis because the comedian wasn't sure how people were responding to his humor. In a 2006 interview with Oprah Winfrey, he explained how, when filming a sketch in blackface, "someone on the set, that was white, laughed in such a way – I know the difference of people laughing with me and laughing at me. And it was the first time I'd ever gotten a laugh that I was uncomfortable with." Shortly after, Chappelle quit the show.  While Chesnutt was certainly not the first African American artist to use humor to depict the horrors of slavery, he was one of the first to reach the American mainstream. The humor disarms readers, helping them cross a psychological threshold and enter a space where a more nuanced conversation about the history of the country can take place. [Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.] Rodney Taylor does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |

| Digital sound archives can bring extinct birds (briefly) back to life Posted: 25 Feb 2022 05:45 AM PST  When people think of extinct animals, they may picture taxidermy, skeletons, 19th-century illustrations or perhaps grainy black-and-white photographs. Until very recently, these were our only ways to encounter lost beings. However, technological advances are making it possible to encounter extinct species in new ways. With a few clicks, we can listen to their voices. In September 2021, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service recommended removing 23 apparently extinct species from the endangered species list. This group included 11 species of birds, as well as various aquatic creatures, a fruit bat and a Hawaiian plant. Of the birds listed as likely extinct, six were recorded while they were still present: the Bachman's warbler, ivory-billed woodpecker and four native Hawaiian and Pacific Island species: the bridled white-eye, Kauaʻi ʻōʻō, large Kauaʻi thrush (kāmaʻo), and poʻouli. Technology capable of recording bird sounds was developed only about a century ago, so these are some of the first now-extinct species whose songs have been preserved.  A not-so-silent springThese recordings are available on the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology's Macaulay Library website, a giant multimedia wildlife archive that holds more than 1 million audio recordings. It includes the sounds of 89% of all bird species on Earth as of 2020, along with photos and videos. The site includes modern sound recordings uploaded by hobbyists, professional sound recorders and scientists, as well as digitized historical recordings captured as long ago as 1929. Scientists use these recordings to study questions such as how bird song evolved and how animals behave. The recordings are also accessible to the public. Macaulay Library director Mike Webster told me that he thinks of the recordings as time capsules: They let us hear what the world used to sound like and preserve our current sounds for the future. In his view, all of the library's recordings are precious. But sounds made by lost species are akin to priceless artworks, like a Rembrandt or a Van Gogh – the very definition of irreplaceable. Sadly, this new genre of extinct animal sounds is expected to grow. Birds have been hard hit by the current ecological crisis: In Canada and the U.S. alone, threats including habitat loss, toxic pesticides and free-ranging domestic cats have reduced bird populations by nearly 3 billion since 1970. Rachel Carson's 1962 book "Silent Spring" inspired a generation of American environmentalists by asserting that if humans continued the destructive behaviors Carson described, such as widespread use of pesticides, the nation could face a spring without birdsong. Sound recordings of extinct birds add a twist to this prediction by letting us hear what's been lost. To see the value of these recordings, let's listen to two species: the ivory-billed woodpecker and the Kauaʻi ʻōʻō. The Lord God BirdThe ivory-billed woodpecker, or ivorybill for short, is an iconic woodpecker species known as the "Lord God Bird" or "Holy Grail Bird" because of its striking appearance and extreme rarity. It was present in the southeastern U.S., with a subspecies in Cuba, but has dipped in and out of presumed extinction since the 1800s. The main causes of its decline are thought to be rapid large-scale deforestation after the Civil War and widespread culling by museum collectors.  This species is the most controversial on the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service list. Some people believe that ivorybills still exist in southeast U.S. forests. The last universally accepted sighting was in 1944, but many others have since been reported, including some by scientists from the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology in the 2000s. Sound recordings of ivorybills were collected in Louisiana in 1935 by Cornell ornithologists, who set out on a cross-country sound recording expedition to capture sounds and images of "vanishing birds" before they were gone. There have been several other claimed sound recordings of ivorybills over the years, including one in 1968 and some in 2006, but only the 1935 recording series is universally accepted by ornithologists and birders. For those still searching for the ivorybill, the 1935 recording is an important tool, especially since it's freely available online. People train their ears on the recording before their searches, and some even use it for "playback" – a technique where the recording is played in potential habitats in the hope that surviving ivorybills will respond. Scientists have also compared contemporary sound recordings they think might be ivorybills with the 1935 recording to suggest that the species is not extinct yet. [Climate change, AI, vaccines, black holes and much more. Get The Conversation's best science and health coverage.] A haunting, one-sided duetThe Kauaʻi ʻōʻō (pronounced 'kuh-wai-ee oh-oh') is a small, dark-colored bird endemic to the Hawaiian island of Kauaʻi and known for its intricate, flutelike "oh-oh" song. It is one of 11 Hawaiian and Pacific Island species on the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service list.  Hawaii has been particularly devastated by environmental loss because of European and American colonizers who tore up delicate island habitats to plant sugar cane and other cash crops. Introduced predators, malaria-carrying mosquitoes and Hurricane Iniki in 1992 also contributed to the birds' demise. Ornithologist Jim Jacobi made a famous recording in 1986 of an individual male Kauaʻi ʻōʻō singing one-half of a duet – with no response. We have no way of knowing if this was the very last bird, but it's hard not to listen as if it were. A remix of a Kauaʻi ʻōʻō song was uploaded to YouTube by Robert Davis in 2009, with an added echo and what he described as "the shrill sounds of commercial exploitation." This remix, which juxtaposes the bird's haunting calls with the cause of their decline, has been viewed over 1.5 million times. In my Ph.D. research about historical bird sound recordings, people frequently bring up their emotional connection to this species' song. One scientist told me he finds it difficult to listen to the recording without crying. Another plays it in lectures to bring home the emotional dimensions of bird loss to students.  The sounds of saving the worldSound recordings give a voice to animals. They help to demonstrate their unique spirits and personalities. They remind us that these beings are invaluable, and that humans have a duty to preserve them. I hope that listening to the voices of extinct birds will lead people to lament those that are already lost, and strive to keep other species singing. Hannah Hunter receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and Mitacs. |

| International law says Putin's war against Ukraine is illegal. Does that matter? Posted: 25 Feb 2022 05:45 AM PST  Both international law and the United Nations Charter say that countries should not invade each other. But who has the ability to enforce those rules? U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres put them to the test on Feb. 24, 2022, when he called on Russia to stop its fast-moving ground invasion of Ukraine. "The use of force by one country against another is the repudiation of the principles that every country committed to uphold. This applies to the present military offensive. It is wrong. It is against the (United Nations) Charter. It is unacceptable. But it is not irreversible," Guterres told reporters at U.N. headquarters in New York. "Stop the military operation. Bring the troops back to Russia. We know the toll of war." At least 137 Ukrainians have been killed by Russian troops since Russia President Vladimir Putin sent tanks and launched missiles into Ukraine in the early hours of Feb. 24, Ukrainian President Vlodymyr Zelensky said on Feb. 24. Zelensky also reported that at least 316 additional Ukrainians have since been wounded in the Russian attacks. Guterres has said that Russia's invasion of Ukraine, a sovereign nation, directly conflicts with the United Nations Charter, an agreement that guides the work of the U.N. and its 193 member states. As a professor of international law, I believe it is important to remember that Putin's invasion of Ukraine is illegal. But enforcing the law is challenging, as armed conflicts around the world demonstrate all too clearly.  What is international law?International law is a set of rules and standards that governs relations between different countries. Countries jointly develop international law and often pass their own national legislation that holds them accountable to these standards. International law addresses almost any subject, ranging from protecting children's rights and preserving the environment to regulating international trade and investment. Much international law is laid out in international treaties — sometimes also called conventions, pacts and covenants. International law is also reflected in the legally binding commitments that countries make when they join international organizations, like the U.N. While not every country joins every treaty, all U.N. members are legally bound by the Charter. Laws of war and peaceThe first quasi-serious attempt to prohibit war in the past 100 years happened in 1928, when the U.S. and France developed the Kellogg-Briand Pact. Dozens of countries agreed to settle their disputes peacefully and to "condemn recourse to war for the solution of international controversies, and renounce it, as an instrument of national policy in their relations with one another." Some of the world's most powerful countries, including Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, India and Japan, also ratified this very short treaty in Paris. But the countries' willingness to abide by the treaty lasted less a decade, and crumbled entirely when World War II erupted in September 1939. Another major international initiative that addresses conflict led to the adoption in 1949 of the four Geneva Conventions, as they are known. These conventions have specific rules that help protect combatants and civilians during war — and are accepted by all countries. The conventions prohibit torture and ensure soldiers' and civilians' rights to proper medical treatment. They also prevent countries from using torture to extract information from prisoners of war and from attacking wounded or sick soldiers. But these conventions only deal with how war should be conducted, not when use of armed force is legal. The most important contemporary rule on conflict is found in the U.N. Charter, which states, "All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations." This wording is significant. The term "use of force" means what it says. Countries cannot avoid their international obligations by pretending their actions are peacekeeping missions, as Putin has said.  Does Russia's invasion of Ukraine violate international law?Under no scenario is Russia's armed invasion of Ukraine legal under contemporary international law and norms. Self-defense is the only justification for use of force against another country, according to international law. This condition is found in the U.N. Charter and is binding for all 193 U.N. member countries. The charter's only clear exception to prohibiting the use of force is self-defense, "if an armed attack occurs" against a country. Rescuing citizens who are trapped or in danger in another country is recognized as a form of self-defense. But these interventions are strictly limited to evacuating citizens, not overthrowing governments. Nothing that Ukraine has done to date could be construed as an "armed attack" on Russia and justify any Russian claim to self-defense. Even if Putin's false claim that Ukraine is targeting Russian-speakers in eastern Ukraine were true, it would not justify the countrywide attacks he has unleashed. Intervening for humanitarian reasons, such as trying to prevent large-scale loss of life or suffering, has been asserted by a few countries and activists as another rationale for use of force. But this justification has not yet been widely accepted, unless the U.N. Security Council authorizes the intervention. It did so when it authorized a U.S.-led military force in Somalia in 1992 to help prevent famine.  How is international law enforced?"Almost all nations observe almost all principles of international law … almost all of the time," a highly respected U.S. law professor, Louis Henkin, wrote in 1979. There is no standing international police force to enforce international law. Compliance is primarily in the hands of countries themselves. The International Court of Justice, created by the U.N. and located in the Hague, Netherlands, decides disputes between countries, including alleged violations of the U.N. Charter. But only 73 countries out 195 have accepted the court's jurisdiction. The U.N. Security Council also has the authority to authorize the use of force under the U.N. Charter in order to maintain international peace and security. This option is unrealistic in the situation of Ukraine because Russia has a permanent seat on the council — along with the other four permanent members: the U.S., U.K., France and China — and thus holds veto power over any decision. Finally, either the U.N. Security Council or individual countries may impose economic or diplomatic sanctions if necessary, as the U.S. and European countries have done. But such actions can have only an indirect impact on deterring or ending a war. There is probably no law, international or domestic, that enjoys universal compliance. The challenge to enforce international law remains — a challenge laid bare most recently and blatantly by Russia's invasion of Ukraine. [There's plenty of opinion out there. We supply facts and analysis, based in research. Get The Conversation's Politics Weekly.] Hurst Hannum does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Home – The Conversation. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

No comments:

Post a Comment