How hateful rhetoric connects to real-world violence |

- Turkey’s threat to derail Swedish and Finnish NATO accession reraises the Kurdish question

- The booming economy, not the 2017 tax act, is fueling corporate tax receipts

- Asia’s tipping point in the consumer class

- Hutchins Roundup: Multinational companies, Treasuries, and more

- Biden’s judicial appointments—still very diverse but numbers may be falling off

- 5 things to understand about pharmaceutical R&D

- Can an inclusive future be envisioned in the digital era?

| Turkey’s threat to derail Swedish and Finnish NATO accession reraises the Kurdish question Posted: 03 Jun 2022 01:08 PM PDT By Ranj Alaaldin Turkey's opposition to Sweden and Finland joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in the wake of Russia's war on Ukraine has elevated the Kurdish question on the international stage. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is attempting to capitalize on the urgency of fortifying Western deterrence by increasing the pressure on the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK). The insurgent group has fought the Turkish state for five decades to secure greater rights for Turkey's Kurds but enjoyed a rapid ascension with the onset of the Syrian civil war and Washington's 2014 decision to partner with its sister organization to defeat the Islamic State group (IS). The PKK has constituted a major component of Turkey's relationship with Europe and the United States for decades, and Erdoğan has initiated several military campaigns into Syria's northeast to suppress the autonomous enclave the PKK's sister organization, the Peoples' Protection Units (YPG), formed in the midst of the civil war. While Turkey may be using the Nordic NATO accession talks to receive Western backing for another campaign, it has a long record of carrying out cross-border incursions against the PKK and Erdoğan may also be trying to secure other concessions, including the lifting of embargoes on Turkey's defense industry. But Ankara's opposition to Swedish and Finnish accession, based on their refusal to extradite PKK members, as well as followers of the Islamic cleric Fethullah Gülen (whom Ankara accuses of instigating a 2016 coup attempt), highlights that the Kurdish question cannot be decoupled from Western security interests. The tectonic shifts that have taken place in the global security order since Russia invaded Ukraine means that the second-order effects of the war against IS and the proximity of the Kurdish question to U.S. and European security interests requires a reprioritization of the issue in the West. Crisis-driven relationsTurkey's conflict with the PKK has long complicated Turkey's relations with the U.S. and its European allies. Relations have been in flux and either enhanced or upended by shifting fault lines in the Middle East since the 2011 Arab uprisings and the emergence of IS. Although the 2013 peace process between the Turkish state and the PKK raised hopes of a lasting settlement, the fragile truce was upended in 2015 by the YPG's ascension in Syria, its refusal to prioritize the fall of the Assad regime, and deep-seated animosities. The result was a renewal of a domestic conflict that has taken on multiple transnational dimensions and produced untold humanitarian crises. Ankara has for decades questioned Europe's commitment to addressing its security concerns. In the 1990s, Greece and Italy provided refuge to the PKK's imprisoned founder and leader, Abdullah Öcalan, and the PKK established an expansive infrastructure, including in Sweden, that allows it to mobilize supporters and resources in Europe and in Turkey. European leaders had hoped to leverage Turkey's EU accession process to improve Turkey's human rights records but talks stagnated more than a decade ago and both sides have effectively given up on it. Similarly, in addition to supporting the YPG, the U.S. has provoked Erdoğan's ire by refusing to extradite the Pennsylvania-based Gülen, while Washington also imposed tariffs on Turkish steel and aluminium after an agreement to release pastor Andrew Brunson fell through in 2018. Ankara did U.S.-Turkey relations no favours by purchasing Russian air defense systems, after which Washington imposed sanctions on Turkey. Turkey's relations with the West will continue to be crisis-driven amid a range of ongoing tensions, including over the conflict in Libya, the eastern Mediterranean crisis, tensions with the EU over the future of 3 million Syrian refugees in Turkey, and NATO expansion in response to Russia's aggression. Putting Turkish responsibility for the current state of affairs to one side, the trans-Atlantic alliance is guilty of failing to establish forward-looking approaches to tumult in Turkey's Middle Eastern neighborhood, opting instead for incoherent and reactive engagement that has put issues like the PKK conflict and broader Kurdish political questions on the back burner. The failure to mitigate the second-order effects of policies designed to address security threats like IS has allowed Ankara to exploit the West's failure to balance the imperative of securing the defeat of the jihadis with the need to manage the security interests of regional actors like Turkey. This has had serious strategic implications, as evidenced by the current dispute over NATO membership and the pressure NATO has faced as a result of the ebb in relations and disputes over the YPG's dominance in Syria. Europe's opportunity?Washington's preoccupation with Russia, China, and Iran, combined with Erdoğan's combative approach to the West and wider fatigue over Turkey's foreign policy, means that it is difficult to foresee a political climate that could enable a proactive U.S. effort to reverse the deteriorating state of relations with Turkey –– even if, ultimately, the Biden administration will need to grant Ankara concessions to secure support for the NATO expansion. However, this may be the moment for Europe to alleviate the strategic fault lines. Although some European countries like France have also embraced the YPG, perceptions of U.S. betrayal in Turkey run deeper and have developed and crystalized over the course of a decade of tumult since the 2011 Arab uprisings. Europe presents Turkey with a different set of dynamics. The EU is by far Turkey's largest trading partner: in 2020, 33.4% of Turkey's imports came from the EU and 41.3% of the country's exports went to the bloc. Total trade between the EU and Turkey that year amounted to €132.4 billion. There are, therefore, limits to how low Turkey-EU relations can go, particularly when considering the dire straits of the Turkish economy. While 58% of the Turkish public believe the U.S. constitutes the biggest threat to Turkey, 60% favour closer ties to the EU and Turks believe the EU's effectiveness for solving global problems is more likely to produce favourable results for humanity. Such dynamics could empower Europe to dial down tensions over NATO and address questions surrounding the future of the PKK's relationship with the U.S.-led anti-IS coalition, within which a number of European countries are key players. Integrating policiesThe West must engage Turkey within the confines of the country's political landscape as it approaches its 2023 elections. There will be limited space to address Turkey's status as a difficult NATO ally or Erdoğan's combative engagement, and no space to revive the peace process with the PKK. The U.S. and Europe could wait out their stormy relationship with Ankara until after the elections, but that banks on a far-from-certain Erdoğan defeat and the notion that it would result in an immediate change in Turkish foreign policy. Alternatively, the U.S. and Europe can start to think about ways to manage the crisis over the YPG to deescalate tensions, and establish much-needed confidence-building measures balancing the West's dependency on the Kurdish fighters against IS with Turkey's security concerns. That will require Europe exercising leadership to establish, in coordination with Turkey and the U.S., a task force that includes personnel who have a track record of executing conflict resolution mechanisms, including ceasefires and peace-monitoring, power-sharing formulas, and revenue-sharing frameworks, which will be important in light of Washington's decision to allow foreign investment in Syria's northeast. It could signal to Ankara that the West is taking its concerns seriously, while also providing a space in which to find mutually beneficial outcomes for all stakeholders in the autonomous enclave. The YPG has banked on European support to enhance its legitimacy, while the PKK has capitalized on such support, and strained Western relations with Turkey, to maintain its grassroots networks in European capitals. Europe, therefore, has sufficient leverage to condition its continued support for the YPG on the organization opening up political space for its local Kurdish rivals. Holding the YPG accountable and enabling Turkish political influence over the future of Syria's northeast will weaken the case for further Turkish military offensives. However, the YPG and the PKK must make their own difficult decisions: it is only a matter of time until the U.S. deems them dispensable assets whose utility as an integral component of the anti-IS campaign is diminished. Russia's invasion of Ukraine has reshuffled Western priorities. Geopolitically, Turkey and the Iraqi army have launched military campaigns to dislodge the PKK from the town of Sinjar in northern Iraq, where the PKK's partnership with Iranian proxy groups and rivalry with Iraqi Kurdistan's ruling party, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), has hindered the anti-IS coalition and U.S. containment of Iran. A PKK withdrawal from Sinjar, per a United Nations-backed agreement, presents one less problem to manage. The Kurds constitute the largest ethnic group in the Middle East seeking a state of their own, with half of the 40 million Kurds residing in Turkey. For Western policymakers, reprioritizing the Kurdish issue provides an opportunity to integrate policies to manage different but interlocked crises in Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Ukraine, while bolstering NATO's northern flank and reinforcing deterrence against Russia. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| The booming economy, not the 2017 tax act, is fueling corporate tax receipts Posted: 03 Jun 2022 06:30 AM PDT By William G. Gale, Kyle Pomerleau, Steven M. Rosenthal Corporate tax revenues boomed in 2021 and some supporters of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) argue that the big tax reductions in the bill deserve the credit (Wall Street Journal, Goodspeed and Hassett). But there is a much better explanation: Last year's strong economic growth, high inflation, and pandemic-related relief legislation increased both corporate profits and the taxes business paid. Soon after the TCJA was passed, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecast corporate tax receipts would fall from 1.5 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2017 to 1.2 percent in 2018 and 1.3 percent in 2019 and remain below the 2017 share until 2022 (Figure 1). Actual corporate tax receipts fell even farther to 1.0 percent of GDP in 2018 and 1.1 percent in 2019. The onset of the pandemic in early 2020 drove the economy into recession and kept corporate tax receipts low. In 2021, corporate tax receipts grew dramatically to 1.7 percent of GDP, higher than CBO's 2018 forecast. For 2022, CBO now forecasts corporate tax receipts will remain strong but fall to 1.6 percent of GDP, only slightly higher than it predicted in 2018. The reasons are pretty clear: In 2021, the economy grew at its fastest pace in three decades and inflation rose at its highest rate in four decades. From early 2020 to early 2021, Congress passed multiple bills designed both to cushion the economic and public health impact of the pandemic and help the economy recover. These measures will pump more than $5 trillion into the economy over their respective 10-year budget horizons compared to the TCJA that totaled $1.9 trillion. The Fed's accommodative monetary policy also stimulated the economy. Fiscal stimulus and easy money raised the demand for goods and services much faster than they increased output, which was restricted by pandemic-related supply constraints. Together, those factors drove prices higher. In general, higher demand translates into higher profits for corporations and higher compensation for workers. Profits increase despite the higher compensation largely because prices of goods tend to respond more quickly to increased demand than wages. Higher corporate profits translate into higher corporate taxes. Profits rose to an average of 12.2 percent of GDP in 2021, more than a percentage point higher than the 11.1 percent average between 2017 and 2019 (Figure 2). Tax legislation also played a role in raising corporate tax receipts in 2021. But much of that was due to timing changes in reporting income. For example, the TCJA accelerated deductions for business investments, which reduced taxes early but increased them later. The 2020 CARES Act permitted business to use that year's losses to reduce prior year taxes. As a result, some corporations accelerated deductions to 2020 and delayed income from 2020 until 2021—all intended to create or increase 2020 losses. In addition, corporations had an incentive to accelerate income into 2021 and delay deductions until after 2021 to avoid proposed tax increases under the Build Back Better Act. Some have suggested that the higher profits were the result of strong business investment. However, this is inconsistent with the data on rate of return for corporations. As profits rose from 2020 to 2021, the rate of return on assets for nonfinancial corporations increased from 7.8 percent to 9.4 percent, higher than the average of 8.4 percent over 2017 and 2019. If higher investment boosted U.S. corporate assets during that period, the pre-tax rate of return on corporate assets would have fallen—not increase, as it did. When Congress passed the TCJA at the end of 2017, official scorekeepers expected corporate tax receipts would decline over the following decade. However, after collapsing during the pandemic, they increased significantly in 2021. A law as comprehensive as TCJA is bound to impact the economy and federal government finances, but TCJA is not a plausible explanation for the large recent increase in corporate tax receipts. Instead, just look to the economic recovery, higher prices from supply and demand imbalances, the aftermath of pandemic relief legislation, and monetary accommodation. The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Asia’s tipping point in the consumer class Posted: 02 Jun 2022 12:45 PM PDT By Wolfgang Fengler, Homi Kharas, Juan Caballero A shadow loomed over Davos as global leaders from business and politics convened in the Swiss alpine resort last week: The war in Ukraine, rising inflation, and the disruption of supply chains dominated the discussions. Last year's optimism of pre-COVID and pre-war conferences has given way to stabilizing business and the international order in the short term. Indeed, short-term economic growth forecasts have been revised downwardly, but not as much as the popular sentiment would suggest. In the long term, faster growth is expected, especially in the emerging economies and Asia. In October of 2021, World Data Lab (WDL) projected that the world would add 132 million new entrants to the consumer class (defined as everyone spending $12 per day in 2017 purchasing power parity (PPP)) in 2022. However, beyond the great extent of human suffering, the economic costs of the war in Ukraine are profound. The war has resulted in trade disruptions and rising energy prices, all of which add to the burden faced by the global consumer. Previous WDL forecasts have been revised, resulting in a loss of 22 million new global entrants to the consumer class in 2022. The most significant damage to consumers comes directly from the war. Ukraine will lose at least 12 million consumers this year alone, while Russia another 5 million. China's zero-COVID policy has resulted in the next most significant revision, with a loss of 3 million consumers since previous forecasts. The war and its ensuing economic consequences have slowed down growth almost everywhere, with people poorer than projected in pre-war scenarios. But despite China's slowing economy, this is largely not the case in Asia: Medium-term growth on the continent has been revised upwardly since October, mostly due to a stronger than expected post-COVID recovery in the Association of Southeast Asian Nation economies and a base effect from new India data. Against commonly held wisdom, the global middle class in Asia has recovered strongly after the COVID shock in 2020. It continues to multiply and is already larger than before the pandemic. Most countries are wealthier than in 2021 due to a continued post-COVID rebound. We now expect Emerging Asia's share of the global economy to expand more rapidly than we thought in October of 2021. Asia's post-COVID recovery is part of a tectonic shift that started at the turn of the century. We can define three distinct periods of the rise of the consumer class:

Asia has been the driver of middle-class growth since 2000, and this trend will continue throughout this decade. The continent is now home to the world's largest consumer market, both in terms of people and spending (Figure 1). Figure 1. The consumer class is shifting East: The next decade will be South Asia's

Source: World Data Lab projections. Asia will face another watershed moment in 2024, when—according to projections by WDL—over half of Asians will be "middle class" (spending $12-120, 2017, in PPP per day) or "rich" (spending more than $120/day). For the first time in the history of the Asian continent, the consumer class will outnumber the vulnerable and poor (see Figure 2). Figure 2. Asia's consumer tipping point will occur in 2024

Source: World Data Lab projections. However, the profile of Asia's consumer class is different from the Western consumer in two important ways:

Table 1. Asia starts to dominate, especially among entry-level consumers

Source: World Data Lab projections. In Factfullness, the late Hans Rosling wrote: "It is easy to be aware of all the bad things happening in the world. It's harder to know about the good things: billions of improvements that are never reported. Don't misunderstand me, I'm not talking about some trivial positive news to supposedly balance out the negative. I'm talking about fundamental improvements that are world-changing but are too slow, too fragmented or too small one-by-one to ever qualify as news. I'm talking about the secret, silent miracle of human progress." Many of the recent developments have reinforced the rapid rise of the Asian middle class. Despite China's COVID lockdowns, a bright horizon lies ahead for the East. The next decade will slowly but surely transition more people out of vulnerability and into the middle class. Consumer spending will increase alongside this transition, and eventually, over half of all money spent will be Asian. Inflation is a risk, especially if interest rates rise and economies slow. However, it is important to realize that some of these fundamental demographic and economic forces have been reshaping Asia's consumer market and these long-term forces are still at play today. In these turbulent times, it is also important to look at the trendlines, not only headlines. For questions regarding the underlying data model, please contact Juan Caballero-Reina (juan.caballero@worlddata.io) This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Hutchins Roundup: Multinational companies, Treasuries, and more Posted: 02 Jun 2022 08:02 AM PDT By Eric Milstein, Nasiha Salwati, Louise Sheiner What's the latest thinking in fiscal and monetary policy? The Hutchins Roundup keeps you informed of the latest research, charts, and speeches. Want to receive the Hutchins Roundup as an email? Sign up here to get it in your inbox every Thursday. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act caused modest declines in profit shifting by multinational companiesThe Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 lowered the federal corporate income tax rate and made U.S. firms' foreign profits tax-exempt with the aim of disincentivizing multinational companies from shifting profits away from the U.S. Javier Garcia-Bernardo of Utrecht University, Gabriel Zucman of the University of California, Berkeley, and Petr Janský of Charles University find that the Act was followed by a 3-5 percentage point decline in the share of profits that U.S. firms booked in foreign countries. Much of this trend was driven by Alphabet, Microsoft, Facebook, and other large companies repatriating intellectual property to the U.S. However, the share of foreign profits booked in tax havens remained unchanged over the 2015-2020 period, the authors find. Specifically, U.S. firms continued to book around half of their foreign profits in low-tax countries in the periods preceding and following the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. "These results suggest that additional policy efforts have the potential to further reduce profit shifting by U.S. multinational companies," the authors conclude. Foreign investors in Treasuries buy high and sell lowForeign investors are more likely than domestic investors to purchase Treasuries when their prices are high and yields are low, find Zhengyang Jiang of Northwestern and Hanno Lustig and Arvind Krishnamurthy of Stanford. This evidence suggests that foreign investors (both private and official sector) are not searching for returns on their investment, but instead value Treasuries for their safe asset properties. The authors find that, since 1980, foreign investors in Treasuries have underperformed domestic investors by 1.5% annually. In addition, foreign investors have underperformed a simple buy-and-hold strategy by 3% annually, suggesting they are actively purchasing Treasuries when they are low-yielding and selling when they are higher-yielding. The authors argue that this trading strategy has lowered the U.S. government's borrowing costs since the 1980s. However, they also document that foreign demand for Treasuries has weakened recently, with foreign investors shifting from net buyers to net sellers of Treasuries during the pandemic. Excise taxes on alcohol reduce consumption among heavy drinkersExploiting an exogenous increase in alcohol excise taxes in Illinois and using household-level data on alcohol purchases over the 2007-2011 period, Henry Saffer and Michael Grossman of the City University of New York and Markus Gehrsitz of the University of Strathclyde find that higher excise taxes reduce alcohol consumption. The percentage decline in alcohol purchases among heavy drinkers (households at or above the 90th percentile of monthly alcohol purchases per adult) was similar to that of non-heavy drinkers, the authors find, challenging the idea that the consumption of heavy drinkers is not affected by price levels. Furthermore, on average, taxes did not increase prices paid for alcohol, because households switched to cheaper alternatives. However, this was not true of low-income households, who did pay more for alcohol after the excise tax increase. Since low-income households comprise a relatively small share of heavy drinkers, "the harm done to the low-income group by tax hikes may be more than offset by the benefits of reductions in heavy drinking," the authors argue. Chart of the week: Lumber prices have fallen sharply since MarchChart courtesy of The Wall Street Journal Quote of the week:"I support tightening policy by another 50 basis points for several meetings. In particular, I am not taking 50 basis-point hikes off the table until I see inflation coming down closer to our 2% target. And, by the end of this year, I support having the policy rate at a level above neutral so that it is reducing demand for products and labor, bringing it more in line with supply and thus helping rein in inflation. This is my projection today, given where we stand and how I expect the economy to evolve," says Christopher Waller, Member, Federal Reserve Board. "Of course, my future decisions will depend on incoming data. In the next couple of weeks, for example, the May employment and CPI [Consumer Price Index] reports will be released. Those are two key pieces of data I will be watching to get information about the continuing strength of the labor market and about the momentum in price increases. Over a longer period, we will learn more about how monetary policy is affecting demand and how supply constraints are evolving. If the data suggest that inflation is stubbornly high, I am prepared to do more." The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Biden’s judicial appointments—still very diverse but numbers may be falling off Posted: 02 Jun 2022 06:18 AM PDT By Russell Wheeler Given the historic confirmation of Judge Ketanji Jackson for the Supreme Court, what about President Biden's so far historic record of lower court confirmations? Last January, outlets reported, for one example, that President Biden had "muscled through the highest number of federal judges in the first year of a presidency in four decades, with picks from a diverse range of racial, gender, and professional backgrounds." In fact, Biden's 81 first-year nominations and 42 confirmations outpaced all predecessors, with the exception of President Kennedy (six decades). Table 1 shows figures for presidents since Ronald Reagan, a period when judicial confirmations grew more contentious.

This post updates key aspects of Biden's record as of June 1 of his second year.

Slowing nominations and confirmationsBiden's 65 confirmations as of June 1 still outnumber those of his six immediate predecessors. But his percentage increase in confirmations over those at first-year's end was the lowest of all but Reagan's. Both Bushes and Clinton more than doubled their first-year confirmation numbers.

Prospects for the rest of 2022We obviously don't know how many more appointments Biden will add by year's end. Table 3 shows that his recent predecessors plowed ahead during the final seven months of their second years.

Three doubled their mid-second year totals. Trump went from 38 confirmations at mid-year to 83 by the end of the year. What's available for Biden?Eighteen Biden confirmations would match Trump's total, and 35 would match George W. Bush's 100. Either is a stretch, but conceivable. Biden would have to almost double his 17-month total to match Clinton's 126 two-year confirmations. What might he and Senate leadership be able to accomplish in an election year, with a Senate schedule that currently provides for two weeks of recess around July 4, recess for most of August and for about half of October through election day on November 8? Of course, if Democrats retain Senate control, post-election confirmations would be regular order. Even if Republicans take control in 2023, a lame-duck Senate may rush through confirmations prior to the 117th's adjournment, pointing to a new norm that the post-2020 election Senate created by confirming 14 of lame-duck Trump's nominees. Current NomineesThirty nominees (11 appellate, 19 district) are pending, but it's not clear whether all will get floor votes. That no Democratic senator has voted against any Biden nominee doesn't mean every Biden nominee is guaranteed confirmation with mid-terms looming in today's 50-50 Senate. Seven district court and four appellate court confirmations have seen 47 or more no votes, so on controversial nominees, a few potential Democratic no votes could mean no Senate floor vote. Some nominees appear in trouble. Tennessee's two Republican senators, for example, opposed the nomination of Andre Mathis (Sixth Circuit); he has waited so far 196 days since nomination, a month longer than any confirmed Biden appellate judge. And the Senate will have to vote to discharge a second nominee from an evenly split Judiciary Committee (Eleventh circuit nominee Nancy Abudu, who worked for the Southern Poverty Law Center). District nominees Dale Ho (New York) and Hernán Vera (California) have, as of June 1, waited over 240 days since nomination, well beyond the 134 median days to confirm Biden's 49 district appointees. And Wisconsin Sen. Ron Johnson is blocking district nominee William Pocan, whom he had endorsed. Assume for the sake of analysis that the Senate confirms nine of the 11 pending appellate nominees (three times as many appellate confirmations so far in 2022) and 16 of the 19 pending district nominees (four fewer than 2022's record so far). Those 25 confirmations, added to 2022's current 23 and 2021's 42 would mean 90 Biden confirmations—a 114% increase over his 2021 total and seven more than Trump's two-year confirmations, ten less than W. Bush's—and 36 less than Clinton's. Prospective NomineesBiden, of course, can submit additional nominees for the thirteen nominee-less appellate vacancies (in place or announced) and the 74 nominee-less district vacancies; three appellate and 47 district vacancies are in courts with no Republican senators. But in recent presidents' second year, the Senate has confirmed very few nominees submitted after June 1 of that year. Although Reagan, both Bushes, and Clinton saw a total of 84 post-June 1 nominees confirmed, more recently, Obama, and Trump saw only two. The same aggressiveness that produced Biden's first year records—including post-election confirmations—might reverse those trends, but it's still likely that Biden's final 2022 confirmation numbers will come mainly from pre-June 1 nominees. Table 4 shows, however, that Biden submitted a comparatively small number of January-through-May nominees.

On June 1, 2018, for example, Trump's 125 nominees exceeded his first-year total by 81%. For whatever reason—perhaps a focus on filling Justice Breyer's seat—Biden's comparable figure is 17%. Beyond 2022So Biden is likely to end 2022 with more confirmations than most recent predecessors but not more than all of them. And, if Republicans control the Senate in 2023, confirmations will slow to a trickle, suggesting at best a modest four-year record. Most of the 50 Republicans have been reliable "no" votes on the Senate floor– median no votes of 41 on Biden's district nominees and 43 on his appellate nominees. Few Republicans in a new Senate majority are likely to support Biden nominees in the 118th Congress, and there may not even be many floor votes at all. Sen. Mitch McConnell nearly shut down the confirmation process the last time he was majority leader with a Democratic president (explained here) (Of 54 district nominees in 2015-16, 33 got hearings but only 11 got floor votes, along with nine 2014 renominees. Three of the seven 2015-16 appellate nominees got hearings, but none got floor votes—only two 2014 renominees. That experience is not predictive—not all players will be the same—but it is suggestive.) Other updatesNominations by Senate DelegationIn Biden's first year, 94% of his district nominees and 11 of his 13 circuit nominees were to courts with two Democratic senators or no senators, minimizing (but not eliminating) tussles with Republican home-state senators. So far, that pattern has continued: five of Biden's six second year district nominees were to courts with no Republican senators, as were five of his seven circuit nominees." Replacing Republican AppointeesFourteen of Biden's 29 first year district appointments and three of his 13 appellate appointments replaced Republican appointees. That pattern continued: eight of 20 district appointees replaced Republican appointees. One of his three appellate appointees replaced a Republican appointee, Helene White, but George W. Bush appointed her as a concession to Michigan's Democratic senators. (Of the 17 appellate judges who took senior status since Biden's election, thus creating vacancies, only four were Republican appointees.) As a result, 2021's year-end 54% Republican-appointee majority among active court of appeals judges has remained basically the same, but the 51% Democratic-appointee majority on the district courts has risen slightly to 55%. Demographic DiversityBiden's 42 first year appointees, as was widely reported (here for example), included far fewer white males than among active judges as a whole. Table 5 shows that his 23 second-year appointees followed the same patterns, save for proportionately fewer Asian-Americans.

Professional BackgroundsCommentators (e.g., here) stressed, as did Biden, the comparatively large proportion of former public defenders among his appointees. Over a third of Biden's 42 2021 appointees had some public defender experience, and almost as many had at least three years' experience. As a proportion of all appointees, they more than doubled public defenders among Obama's appointees, and were much more than other predecessors. Biden's 23 appointees in his second year include six with some public defender experience, five with three or more years. In summary, Biden so far in 2022 continues to change the demographic and pre-professional face of the judiciary. Although he also continues to score more confirmations than all recent predecessors, by year's end, he likely will no longer top that roster. Data from fjc.gov, uscourts.gov and my own data sets. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| 5 things to understand about pharmaceutical R&D Posted: 02 Jun 2022 06:00 AM PDT By Richard G. Frank, Kathleen Hannick At the heart of the policy debate aimed at controlling the price of prescription drugs is a concern that pricing policies, which would reduce revenues for brand name prescription drugs, would result in fewer "new cures." The logic underlying this concern is as follows: higher prices equate to higher returns to investors that then bring more capital into drug development, which is the lifeblood of innovation. Therefore, the logic goes, reducing prices will reduce returns, which will reduce the capital invested, thus slowing innovation. More colorful versions of this argument include the head of PhRMA, the main pharmaceutical industry association, threatening that recent legislation aimed at negotiating drug prices, known as H.R. 3, would cause a 'nuclear winter' for innovation. To better understand the extent to which innovation and prices are tied together, we identify five important things to know about pharmaceutical research and development (R&D) and its relationships to drug prices and revenues.

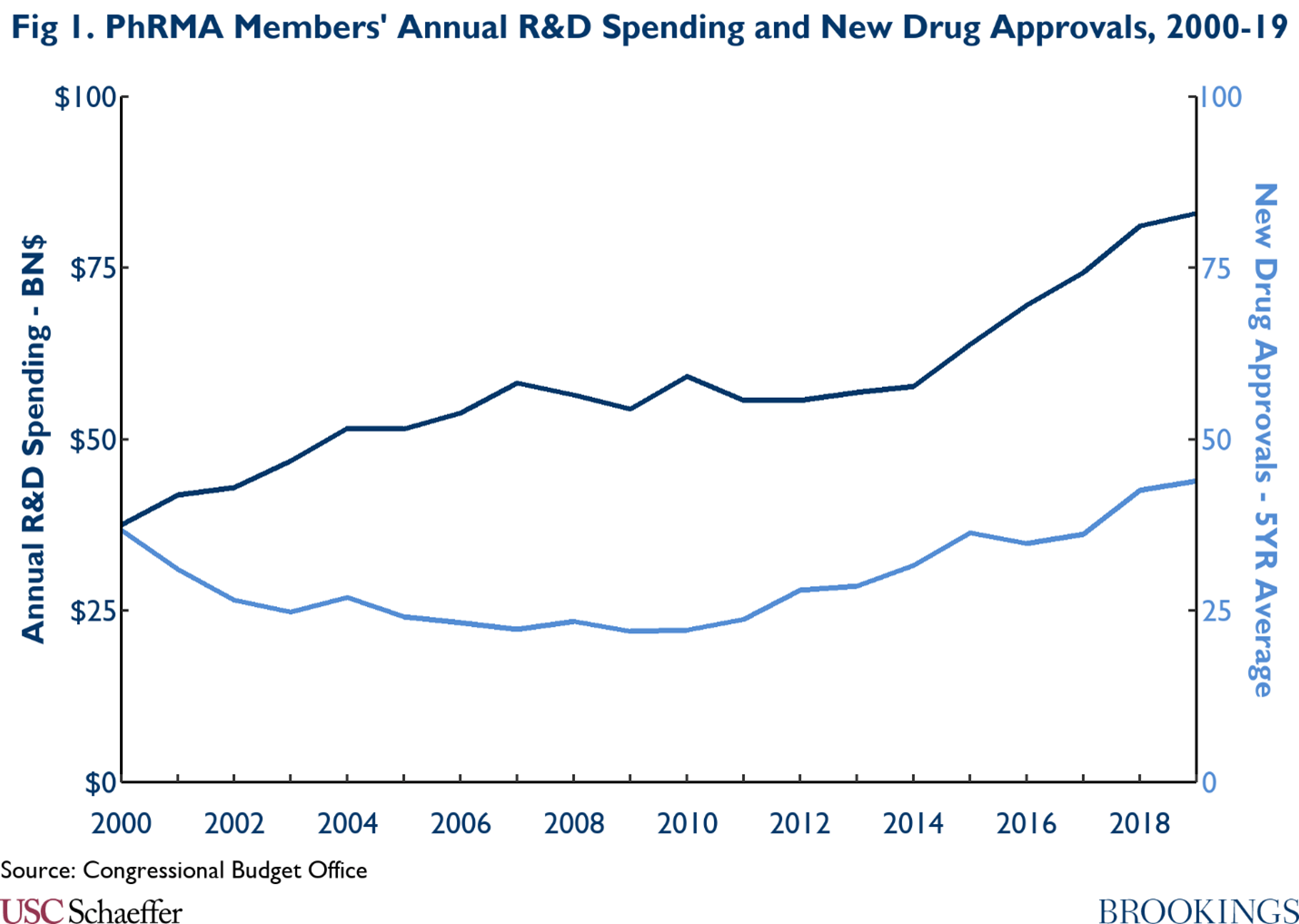

We assemble extant data and evidence on each of these issues as well as make observations pertaining to these questions. Observation 1: The relationship between R&D spending and the supply of new drugs is modestWhile it may seem in theory that high levels of spending on R&D would result in high production of new drugs, the empirical evidence suggests that the relationship between R&D spending and new drugs is modest. As seen in the graphic below, annual R&D budgets for PhRMA members have been on the rise, growing from $37.5 billion in 2000 to $83.0 billion in 2019. However, during the same time, the 5-year average for new drug approvals went from 36.8 in 2000, then declined for nearly a decade hitting a low in 2009 with 22 new drugs, before the 5-year average steadily increased to 44 new drugs in 2019. Furthermore, the correlation between PhRMA's spending on R&D and the 5-year average for new drug approvals was only moderately positive at 0.58.

Beyond high levels of spending on R&D by PhRMA members, it is also notable that the sources of innovation are shifting, further complicating the relationship between R&D spending and the supply of new drugs. According to IQVIA's report "Emerging Biopharma's Contribution to Innovation,” emerging biopharmaceutical (EBP) companies are defined as companies that spend less than $200 million annually on R&D or have less than $500 million in global revenue. In 2018, EBP companies accounted for 80% of total pipeline projects from discovery to filing, while large pharmaceutical companies, those that have annual global sales over $10 billion, only accounted for 15% of pipeline projects. Further, EBP companies' dominance over R&D activities has only grown over time. In 2003, EBP companies accounted for 52% of the late-stage R&D pipeline, while large pharmaceutical companies made up 36%. 15 years later in 2018, EBP companies undertook 73% of the late-stage research activity and large pharmaceutical companies' share fell to 19%. Moreover, in 2021, EBPs originated 53% of all new drugs and accounted for 76% of launches.[1] As demonstrated, EBP companies are driving the majority of innovation with R&D budgets that are smaller than large pharmaceutical companies. Further evidence from the House Committee on Oversight and Reform and the FDA show how the largest pharmaceutical companies' sizable R&D budgets do not necessarily coincide with large numbers of new drugs. Through its ongoing investigation of drug pricing, the Oversight Committee recently published total R&D expenditures for 14 of the largest pharmaceutical companies by market capitalization.[2], [3] Combined, these companies' R&D expenditures totaled $121 billion in 2019. During that year, the FDA approved 50 new molecular entity (NME) applications, of which, only 10 (20%) came from five of these large pharmaceutical companies, while the other nine companies had no NME approvals that year. From 2016-20, these 14 companies spent a total of $521 billion on R&D. During that time frame, there were 236 new molecular entities approved by the FDA. Of the large pharmaceutical companies studied, 11 of the firms accounted for 48 (20%) of those approvals while the other three companies had no new molecular entity approvals in those 5 years. Observation 2: It costs a lot to bring a new drug to market on average, but the actual amount varies widely.Remarkably, estimating the cost of bringing new drugs to market has been a source of passionate debate despite the rather dry technical issues involved in developing such estimates.[4] The fever of the debate stems from high R&D costs being used to justify high prescription drug prices. Studies of the cost of drug R&D have covered a range of drug types, a range of therapeutic classes, varying choice of user cost of capital used to make capitalized estimates of R&D costs, and have used diverse samples of manufacturers.[5]The research uses a variety of methods that, in turn, produce a wide range of estimates; thus, the simple comparison of estimates can result in misleading judgments. The many ways to cut the data and to structure assumptions has unsurprisingly led to a wide range of estimates for the cost of drug development. The most recent and comprehensive review of studies estimating the costs of bringing a new drug to market was delivered by Schlander and colleagues in 2021.[6] The range of estimates of the average capitalized cost of bringing a new drug to market spans from some as low as $161 million (in 2019 dollars) to as high as $4.5 billion. The difference between the mean and median estimates was also large, reflecting the underlying variation in the costs of bringing a new drug to market. There are also disparities in cost estimates based on the observed period of drug development. The weight of the evidence suggests that average capitalized R&D (that includes all phases of R&D) ranges from $1.3 to $2.5 billion. The median capitalized R&D is 5% to 13% lower than the average.[7] Several parameters vary considerably and underpin some of the observed variation. Among the most salient differences are the composition of the sampled drugs, development times, and the user cost of capital applied. Three parameters are especially important: the sample of drugs studies, the success rates for the R&D process, and the user cost of capital. In one of the most prominent estimation exercises, DiMasi, Grabowski, and Hansen use data for costs and drug launches from a sample of so-called "big Pharma" products.[8] They reported mean and median capitalized R&D costs per new drug to be $2.6 billion and $1.9 billion respectively in 2013 dollars, a 31% difference. If one applies weights to new drugs as they appear in the population of new drugs approved by the FDA instead of the sample used by DiMasi and colleagues, estimated R&D costs fall by over half to a mean of $1.01 billion and a median of $762 million.[9] This finding results from the fact that the share of orphan drugs in the DiMasi, Hansen, and Grabowski sample is much smaller than the share of orphan drugs among all new drugs, as well as the fact that orphan drugs cost less to bring to market. Additionally, the success rates of human testing vary in a number of dimensions. In the studies reviewed by Schlander and colleagues, reported success rates varied by a factor of more than four (9% to 39%). The success rate varies according to factors such as the types of drug classes studied and the organization of the development process (partnerships, joint ventures, licensing agreements, solo development). The sampling and therapeutic mix of drugs used for estimation can therefore have potentially powerful effects on estimates. For example, the share of licensed-in and partnership arrangements in drug development have increased substantially over time. Recent research shows that these arrangements involve significantly higher success rates. Taking such changing development patterns into account have been projected to drop estimates of average capitalized development costs by 24%.[10] The third salient parameter driving results in this literature pertains to assumptions about the user cost of capital. The literature, as noted earlier, uses several different user costs of capital assumptions. The user cost of capital parameters most often used are 10.5% and 11%. However, some studies have used 7%, 8%, 9%, and 11.5%. To illustrate the significance of these assumptions, most studies find that the time cost of money component of the capitalized costs accounts for between 35% and 51% of average capitalized costs of R&D. When a lower cost of capital level of 7% was used, the time cost of money accounted for about 21% of the total.[11] In sum, the samples drawn to study R&D, the success rates applied to the samples, and the user cost of capital assumed can move estimates by 50% or more, which suggests much uncertainty about the true costs of new drugs and the likely costs of future development efforts. Observation 3: Pharmaceutical companies allocate retained earnings and other financial resources to R&D and shareholder payouts.During a recent Senate hearing on pharmaceutical policy, a representative of the industry claimed that "companies depend on profits to sustain biopharmaceutical investments."[12] This declaration creates the impression that profits finance R&D. Clearly, this conclusion does not generalize, since many innovative emerging pharmaceutical manufacturers bring new drugs to market prior to collecting any revenues. Recent analyses of industry balance sheets also reveal a more complicated picture. The average percent of global revenue accounted for by shareholder payouts from 2009-2018 was 29%, or 106% of net income. Shareholder payments include stock buybacks and dividend payments. The average percent of global revenue accounted for by R&D was 17%, or 93% of net income. Thus, for the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world, R&D plus shareholder payouts sum to 199% of net income. Clearly, R&D is not being funded primarily by retained earnings. Debt during the 2009-2018 period for the top 18 firms averaged around 58% of global revenues, or over 200% of net income. Debt has more than doubled since 2009, suggesting that there is more to R&D funding than simple retained earnings. This is in large measure due to the high levels of payouts to shareholders in the form of dividends and stock buybacks.[13] A recent report delves further into the finances of the pharmaceutical industry. Studying the world's 27 largest pharmaceutical companies from 2000 to 2018, researchers found that the industry has undergone "mass financialization" during this time. Between 2000 and 2018, net revenues among the 27 companies grew over 240% from $300 billion to almost $725 billion. During that same time period, R&D spending as a percentage of net sales grew modestly from 12% to 17%. Investor payouts and stock buybacks, however, grew from $30 billion (10% of net sales) to $146 billion (20% of net sales) accounting for $1.54 trillion in total over the time period studied. As a percentage of R&D spending, dividends grew from 88% of total investment in R&D in 2000 to 123% in 2018. Furthermore, operational investments in fixed capital, such as machines and buildings, shrunk during this period, while financial investment in intangible assets, such as intellectual property rights and goodwill, grew substantially from 13% of total assets in 2000 to 51% of total assets in 2018. The graphic below details how R&D, dividends, fixed capital, and debt as a percentage of net sales have changed over time.

Observation 4: The number of new drugs is a poor metric for drugs that expand treatment capabilities and offer "new cures."The House of Representatives' version of Build Back Better (HR 5376 or BBB) would reduce global revenues for pharmaceutical U.S. manufacturers by about 7%. The CBO score for the legislation projected that this decrease would result in two fewer drugs in the first decade, 23 fewer in the second decade (5% decline), and 34 in the third (8% decline).[14] The pharmaceutical industry claimed that this projection was too low, suggesting the impact on new drug launches would be much greater. Most of the evidence on which all sides base their claims come from the same "natural experiment" of when Medicare expanded to include the drug benefit (or Medicare Part D) in 2006. Research consistently showed that as the market grew due to the expansion of drug coverage stemming from implementation of Medicare Part D, the number of new drugs that came on the market significantly increased. The key policy question for assessing the trade-off between price and innovation is: what is the likely impact of reduced revenues for a set of "high priced" drugs on the supply of "new cures"? This is where the story gets complicated. Interpretations of the evidence on the trade-off between prices and reduced innovation turn on several points: (1) What are the health impacts of new drugs? (2) What do market expansions-contractions do to science? and (3) Can policy design affect the quality of new drugs launched? The evidence shows that when Medicare expanded to cover drugs under Part D, the number of drugs coming to market increased, which was the basis for projecting declines in new drugs when revenues fall. However, research by Dranove and colleagues show that the new launches following Part D implementation were almost entirely in areas where there were already existing therapies (five or more, rather than two or fewer). [15] They also found that few were truly innovative. Research by Amy Finkelstein provides some insight into the possible mechanisms behind the Part D expansion. [16] Her work argues that companies took existing products that were "on the shelf," but not sufficiently profitable with the smaller market, and launched them as the market grew. Research by Byrski and colleagues extends this line of analysis. [17] They examine the same data on the impact of the creation of Part D and then looked at the impact of the market expansion on new drugs, new patents, and new published science. The authors found that they could replicate the increase in new drugs found by prior studies. They also found no overall evidence of increases in patenting or new published science. The implication of these results is that while market expansions increase the number of product launches, the drugs that result do not broadly offer significant health impacts and they do not drive overall scientific advances. Thus, new science and new cures are not primarily driven by price. Observation 5: Much of big PhRMA's R&D is directed at extending the franchises of existing drugs through line extensions.We reviewed all FDA approvals of brand name products for the period 2011-2021.[18] We identified product launches that consisted of New Molecular Entities (NMEs) and combination products involving an NME. We call these new drugs. All other brand name product launches involve only existing products. This includes adding new indications to labels, developing new formulations, changing dosage strengths, and new combinations of existing drugs. Using our definition of new drugs, NMEs, account for 36% of the brand-name launches. If we were to count new combinations, the new product share rises to 46%. In any case, much activity that falls under the heading R&D does not involve new drugs. This is exemplified by industry reports highlighting large R&D investments in new formulations for existing blockbuster drugs. For example, Bristol-Myers spent a large part of its 2018-19 R&D dollars for line extensions for existing blockbusters Opdivo and Yervoy, and Sanofi testified in the Senate that only 33 of its 81 R&D projects were for new chemical entities. Concluding ObservationsMuch has been made of the threat to new drugs and "new cures" posed by legislation such as Build Back Better. However, looking carefully at the data on R&D patterns and evidence on how the industry responds to market expansion suggests a less dramatic impact of reduced revenues on R&D. Thus, modest changes in the size of payments to the pharmaceutical industry would likely have little impact on the future health of Americans. This is especially the case since the Build Back Better legislation promises three things: 1) a focus on drugs that have exceeded "normal" durations of market exclusivity; 2) safe harbors for drugs developed by smaller biotechnology companies; and 3) that the U.S. will continue to pay the highest prices for brand name drugs in the world by a significant margin. The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation. [1] IQVIA, Global Trends in R&D: Overview through 2021, February 2022. [2] Committee on Oversight and Reform, Drug Price Investigation: Industry Spending on Buybacks, Dividends, and Executive Compensation, July 2021. [3] The 14 companies include: AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche, and Sanofi. [4] See for example: Light DW, R Warburton, 2005, Extraordinary Claims require extraordinary evidence: comment, Journal of Health Economics 24(5):1030-1033. [5] Drug types include orphan, small molecules, biologic. Therapeutic classes include cancer drugs, anti-infectives, influenza vaccines. Varying choice of user cost of capital used to make capitalized estimates of R&D costs include 7%, 9%, and 11%. Diverse samples of manufacturers include big Pharma, biotech, and overall industry. [6] Schlander M, K Hernandez-Villafuerte, C-Y Cheng, et al, 2021, How much does it cost to research and develop a new drug? A systematic review and assessment; PharmacoEconomics 39:1243-1269. [7] Authors calculations based on Schlander et al Table 1. [8] DiMasi JA, RW Hansen, HG Grabowski, 2016, Innovation the pharmaceutical industry: new estimates of drug development costs, Journal of Health Economics 47(1): 20-33. [9] US DHHS, 2016, Prescription Drugs: Innovation, Spending and Patient Access, Report to Congress, December. [10] Authors' calculation based on DHHS 2016 Tables 2 and 6. [11] Prasad V, S Mailankody, 2017, Research and development spending to bring a single cancer drug to market and revenues after approval, JAMA Internal Medicine 177(11):1569-1575. [12] Ezell SJ, Testimony Presented at Senate Finance Committee Hearing on Drug Price Inflation: An Urgent Need to Lower Drug Prices in Medicare, March 16, 2022. [13] Sources for this paragraph are as follows: Financialization of the U.S. Pharmaceutical industry William Lazonick, Öner Tulum, Matt Hopkins, Mustafa Erdem Sakinç, and Ken Jacobson, The Academic-Industry Research Network December 2, 2019; and Private gains we can ill afford The financialization of Big Pharma April 2020 s Sarphatistraat 30 1018 GL Amsterdam The Netherlands T: +31 (0)20 639 12 91 F: +31 (0)20 639 13 21 info@somo.nl www.somo.nl The Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO) plus recent reviews of Form 10Ks. [14] The CBO estimates rise over time because revenue impacts matter more in out years when fewer initial investments have been locked into place. [15] Dranove, D., Garthwaite, C. and Hermosilla, M., 2014. Pharmaceutical profits and the social value of innovation (No. w20212). National Bureau of Economic Research. [16] Finkelstein, A. (2004). Static and Dynamic Effects of Health Policy: Evidence from the Vaccine Industry. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 119(2), 527—564. [17] Byrski, D, F Gaessler, MJ Higgins, Market Size and Research: Evidence from the Pharmaceutical Industry; Max Planck Institute Research Paper 21-16, May, 2021. [18] Drugs@FDA data from 1/2011-1/2021 This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Can an inclusive future be envisioned in the digital era? Posted: 01 Jun 2022 12:17 PM PDT By Zia Qureshi We are living in what has been aptly termed the digital era, a time of rapid technological change led by digital technologies. The new technologies are reshaping economies—and societies. We may be on the cusp of a significant deepening and acceleration of the ongoing digital transformation of our economies and societies as artificial intelligence (AI) generates a new wave of innovations. The COVID-19 pandemic has given added impetus to automation. The future is arriving at a faster pace than expected. Advances in digital technologies hold great promise. They create new opportunities and avenues to boost economic prosperity and raise human welfare. But they also pose new challenges and risks. As the new technologies transform markets and nearly every aspect of business and work, they have highlighted, and can deepen, economic and social fault lines across advanced and developing economies. One major fault line is economic inequality, which has been rising in many countries over the period of the boom in digital technologies. The rise in inequality has been more pronounced in advanced economies, notably the United States. Rising inequality and related disparities and anxieties have been stoking social discontent and are a major driver of the increased popular disaffection and political polarization that are so evident today. An increasingly unequal society can weaken trust in public institutions and undermine democratic governance. Rising inequality has emerged as an important topic of political debate and a major public policy concern. Against this background, a recently published report, An Inclusive Future? Technology, New Dynamics, and Policy Challenges, examines the opportunities and challenges of digital transformation. This report is part of a current initiative at Brookings—Global Forum on Democracy and Technology—that seeks to promote ideas and policies to manage technological change to build inclusive prosperity and strengthen democratic societies. Technological transformation has been altering market dynamics in ways that push inequality higher within economies. This has been happening through three channels: More unequal distribution of labor income with rising wage inequality as technology shifts labor demand from routine low- to middle-level skills to new, higher-level skills; shift of income from labor to capital with increasing automation and decoupling of wages from firm profitability; and more unequal distribution of capital income with rising market power and rents in increasingly concentrated and winner-takes-all markets. These dynamics are more evident in advanced economies but could increasingly impact developing economies as the new technologies make deeper inroads there. Not only has inequality been rising, but the expected productivity dividend from digital technologies has not fully materialized. The potential of the new technologies to deliver higher productivity and economic growth is sizable. But productivity growth has slowed rather than accelerated in many economies as digital technologies have boomed. Firms at the technological frontier have captured the lion's share of the returns from the new technologies. Productivity growth in these firms has been strong, but it has stagnated or slowed in other firms, depressing aggregate productivity growth. With slower productivity growth, economic growth has trended lower. So, the proverbial economic pie is not only more unequally distributed, it is also growing more slowly. Looking ahead, absent countervailing policies, AI and related new waves of digital technologies and automation could increase inequality further. Even as new technologies increase productivity and produce greater economic affluence, and new jobs and tasks emerge to replace those displaced to prevent large technological unemployment, inequality could reach much higher levels. Continuing and large increases in inequality may not be a sustainable path given associated social and political risks. While within-country inequality has been rising, inequality between countries has been falling. Faster-growing emerging economies have been narrowing the income gap with advanced economies. But technological change poses new challenges for this global economic convergence. Manufacturing-led growth in emerging economies has been driven by their comparative advantage in labor-intensive manufacturing based on large populations of low-skilled, low-wage workers. This source of comparative advantage increasingly will erode as automation of low-skilled work expands, disrupting traditional pathways to development. The title of the new report poses a question: Can an inclusive future be envisioned in the digital era? The answer to that question is yes. Large and persistent increases in inequality are not an inevitable consequence of technology. The challenge for policymakers lies in harnessing transformative change spawned by current and prospective advances in technology to promote more inclusive growth and development. Public policy in general has been slow to rise to the challenge. Policies have lagged shifting growth and distributional dynamics as technology reshaped markets, business models, and the nature of work. The result has been both a failure to capture the full productivity potential of the new technologies and a failure to counteract some of the effects of these technologies that increase economic inequality. With more responsive policies, better outcomes are possible. The reform agenda spans product and factor markets to enable broader participation of firms and workers in the opportunities created by the new technologies. It includes competition policy, regulatory frameworks governing the new digital economy, the innovation system, education and training, labor market policies and social protection, and policies to reduce the digital divide. It also includes tax policy reform. A theme unifying much of this reform agenda is that, in capturing the full promise of digital transformation, economic growth and inclusion are not competing but complementary objectives. In many of these areas of national policy reform, more research, fresh thinking, and experimentation will be needed to align institutions and policies with the profound technology-driven changes in the functioning of markets and economies. At the international level, new global frameworks and rules will be needed as globalization goes increasingly digital. Technology can potentially slow global economic convergence by altering patterns of comparative advantage. But as it disrupts some traditional pathways to growth and development, it also offers new opportunities for developing countries that successfully recalibrate their growth models to the new technological paradigm. Adapting to the new technologies is a big challenge for policymakers. But that is not the only challenge. A related challenge is to shape technological change itself to put it to work for broader groups of people and better meet the needs and interests of economies and societies. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Turkey’s threat to derail Swedish and Finnish NATO accession reraises the Kurdish question. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

No comments:

Post a Comment