How hateful rhetoric connects to real-world violence |

- Mothers are being left behind in the economic recovery from COVID-19

- The coming COVID-19 baby bust is here

- Assessing the social and emotional costs of mass shootings with Twitter data

- What will Facebook’s ban mean for Donald Trump’s future?

- The hacker, the tax haven, and what $200 million in offshore deposits can tell us about the fight against illicit wealth

- Figures of the week: Africa’s renewable energy potential

- How tax incentives can power more equitable, inclusive growth

- Linking criminal justice reform and health policy: Incarceration rates and HIV prevalence

| Mothers are being left behind in the economic recovery from COVID-19 Posted: 05 May 2021 09:01 PM PDT By Lauren Bauer "It is unclear whether child-care issues will prevent women from returning to employment as the economy recovers," wrote economist Betsey Stevenson (University of Michigan) in a July 2020 essay for The Hamilton Project. In the essay, Stevenson laid out a set of economic indicators and issues that if left unresolved, could lead to permanent labor market scarring following the COVID-19 pandemic. In recent months, the concerns raised by Stevenson about women and the labor market have, unfortunately, come true. In the paper "Ten economic facts about how mothers spend their time," my colleagues and I document some of the ways in which the labor market trajectory of mothers prior to the pandemic has not only been disrupted, but meaningfully turned back. In this piece, I provide new evidence that mothers — particularly mothers of children under five and unmarried mothers — are being left behind in the economic recovery from COVID-19. The COVID-19 pandemic has widened labor force participation gaps between mothers and fathers.[i] The LFPR of mothers overall was about 3.5 percentage points lower in March 2021 than in January 2020 (not shown) while fathers' LFPR was down 1 percentage point. Moreover, the age of the children in the household contributes to differences in labor force participation rates (LFPR) during the COVID-19 pandemic (figure 1). While LFPRs of mothers whose youngest child is a teenager have rebounded to about 1.5 percentage points below its January 2020 level, mothers whose youngest children is under 13 are more than 4 percentage points below. In January 2020, single mothers had the highest LFPR of the female groups at just over 81 percent. Since then, the LFPR fell the most among single mothers of the groups examined — with a decline of about 7.5 percentage points — and their rate has been the slowest to recover. As of March 2021, the LFPR for single mothers is a full 5 percentage points below its January 2020 rate. Many have found evidence that school closures have resulted in women exiting the labor market. The Fall Survey of Mothers with Young Children (Fall SMYC) asked why: whether they left their job due to child care responsibilities and whether respondents lost their job because of an employer's decision. In addition, among those who reported being in the labor force as of October 2020, the survey asked two other questions: whether the respondent "had a serious conversation about leaving your job or formally shifting to part-time work to take care of your child?" and "How difficult would you say it is for you personally to balance the responsibilities of your work with the responsibilities of your family?" Figure 2 shows exclusive categories of responses to these four questions, by marital status and the age of one's youngest child. About 14 percent of unmarried mothers and mothers whose youngest child was under the age of 6 reported that they left their job due to child-care responsibilities in 2020 compared with 8 percent of mothers with children 6 to 12. While more than 7 percent of each group lost their job during the COVID-19 pandemic from March to October, 11 percent of unmarried mothers did. Taken together, a quarter of unmarried mothers reported that they left or lost their job in 2020 compared with 18 percent of married mothers. Mothers with children under 6 were most likely to report having a serious conversation about leaving their job or reducing their hours due to child-care challenges and/or finding it very difficult to balance work and family responsibilities. However, these weighty conversations and daily stresses were reported with high frequency among all of those who were employed at the time of the Fall SMYC and who did not report having left or lost their job. Families with children, and specifically single mother households, have experienced high levels of material hardship over the past year. Figure 3 shows the share of adult respondents to the Census Household Pulse Survey who reported food insecurity at key points over the past year. This analysis, by Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach and Abigail Pitts, describes rates of very low food security (i.e., hunger) and low food security for single mothers, respondents with children, and all respondents during three survey weeks: the beginning of the pandemic (April 2020), the peak of food insecurity (December 2020), and just a few weeks ago (late March 2021). The Schanzenbach and Pitts analysis finds that throughout the pandemic, single mother households have had the highest rates of food insecurity, the highest rates of hunger, and the highest ratios of hunger to low food security. As of late March 2021, single mothers had a higher rate of food insecurity (almost 35 percent) than respondents with children or all households had at any point during the pandemic. During the COVID-19 pandemic, not everyone had the opportunity or flexibility to care for their children and keep their job, not everyone had a spouse or partner with whom one could share caregiving burdens, not everyone has an employer or job responsibilities that allow for juggling, not everyone could make ends meet. As of March 2021, mothers are lagging behind fathers in returning to pre-pandemic LFPRs and are experiencing material hardship as measured by food insecurity. As the U.S. exits the acute COVID-19 crisis, long-run trouble finding affordable child-care slots, child-care workers experiencing high levels of job loss, and the diminished will hold some mothers back. This analysis shows that absent a care infrastructure to support those with the highest caregiving responsibilities — mothers with children under five and unmarried mothers — in times of crisis, many will leave the labor force to care for their children, will struggle to come back, and will cope with a lifetime of consequences. On May 12, The Hamilton Project will hold an event that offers solutions to support women in the labor market, "Rethinking the economics of child care and paid leave: Policies to protect workers and families." At this event, The Hamilton Project will release new policy proposals on expanding access to high-quality affordable child care (from Elizabeth E. Davis and Aaron Sojourner) and paid family and medical leave (from Tanya Byker and Elena Patel). The Hamilton Project has offered many proposals to address child care (by Elizabeth Cascio, Elizabeth Cascio and Diane Schanzenbach, Bridget Terry Long, and James Ziliak) and paid leave (Nicole Maestas and Christopher Ruhm) in addition to volumes on economic downturns (Recession Ready) and economic security for women (The 51%: Driving Growth through Women’s Economic Participation). Endnotes: [i] Reductions in the labor force participation rate come from labor market exits; those who are working or unemployed (i.e. actively seeking work) are labor force participants while those who are not working (for whatever reason include caregiving) or are not seeking work are not in the labor force. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The coming COVID-19 baby bust is here Posted: 05 May 2021 01:45 PM PDT By Melissa S. Kearney, Phillip B. Levine Official birth data from the final months of 2020 were released last night from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Center for Health Statistics. The data confirm what many suspected and what we predicted back in June 2020 and further discussed in December 2020: nearly 40,000 "missing births" in the final month and a half of 2020, which would have otherwise been conceived in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. There were 53.9 births per 1,000 women (at an annualized rate) in the last quarter of 2020, in October, November, and December. That is substantially lower than the 57.6 annualized births per 1,000 women in the last quarter of 2019. However, not all of that decline can be attributed to the early stages of the pandemic. Birth rates have fallen steadily in the U.S. since 2007. Assuming births would have fallen between 2019 quarter 4 and 2020 quarter 4 at the same rate by which they fell between 2018 quarter 4 and 2019 quarter 4 (specifically, 2.3 percent), the observed drop between the final quarters of 2019 and 2020 incorporates a 4.3 percent "excess" decline. (Figure 1 plots quarterly birth rates for 2018, 2019, and 2020.) Since the effects of the pandemic in the U.S. really took hold in March 2020, only missing births from the second half of the quarter can reasonably be attributed to effects of the pandemic. The estimated COVID impact on births is thus twice as large – an excess decline of 8.6 percent.

This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Assessing the social and emotional costs of mass shootings with Twitter data Posted: 05 May 2021 11:48 AM PDT By Mary Blankenship, Carol Graham Mass shootings that result in mass casualties are almost a weekly occasion in the United States, which—not coincidentally—also has the most guns per capita in the world. Viewed from outside the U.S., it seems that Americans are not bothered by the constant deadly gun violence and have simply adapted to it. Yet, our analysis of the well-being costs of gun violence—using Twitter data to track real-time responses throughout the course of these appalling events—suggest that is not necessarily the case. We focus on the two March 2021 shootings in Atlanta and Boulder, and compare to similar data for the "1 October" (Las Vegas) and El Paso shootings a few years prior. (Details on our methodology can be found at the end of this blog.) A reason for the one-sided debate on guns is that beyond the gruesome body counts, we do not have many tools for assessing the large—but unobservable—effects of this violence on family members, friends, and neighbors of the victims, as well as on society in general. By assessing how emotions evolve over time, real changes can be seen in Twitter messages. Our analysis shows that society is increasingly angered by gun violence, rather than simply adapting to it. A striking characteristic of the response to the 1 October shooting is the immediate influx of users sending their thoughts and players to the victims and the Las Vegas community. Figure 1 shows the top emoji usage and "praying hands" being the most frequently used emoji. Although that is still the most used emoji in response to the other shootings, the margin between "praying hands" and other emojis has substantially decreased in recent responses to Atlanta and Boulder. Our focus is on the "yellow face" emojis, which can correlate to six primary emotions categories: surprise, sadness, disgust, fear, anger, and neutral. While the majority of face emojis reflect emotions of sadness in the 1 October and El Paso shooting, new emojis like the "red angry face" show greater feelings of anger in the Atlanta and Boulder shootings shown in Figure 3. Figure 1. Top 10 emojis used in response to the 1 October shooting

Source: Authors Figure 2. Top 10 emojis used in response to the El Paso and Dayton shootings

Source: Authors Figure 3. Top 10 emojis used in response to the Atlanta and Boulder shootings

Source: Authors Taking a deeper look at the emoji usage of the Atlanta and Boulder shootings, the "praying hands" emoji usage was often paired with "broken heart" and "sobbing face" emojis, and belonged primarily to retweets (above 80 percent) of tweets made by celebrities, politicians, and news correspondents. Among other things, this demonstrates the power that users with a large number of followers have on the response and sentiment shared online. The "US flag" emoji was not used as a sign of patriotism but represents tweets from outside the United States reporting on the event. For the Atlanta and Boulder shooting, the "tears of joy" emoji was often used in tweets claiming that the Atlanta shootings did not pertain to race and that the belief had been perpetuated by "mainstream media" or in tweets not related to the shooting. The "red angry face" was widely used in tweets that expressed disdain and confusion over the gun violence and mass shootings. Hashtags are another powerful tool used in social media to express opinions and reactions to recent events. In the 1 October shooting, hashtags like #prayforvegas were popular, as seen in Figure 4. Another notable hashtag used is #vegasstrong, which gained popularity as Las Vegas was trying to recover from the tragedy and now, variations of #*cityname*strong are a popular reaction to mass casualties since 2017. Yet as American communities become accustomed to recurring mass gun violence, emboldening becomes more difficult. As in Figures 5 and 6, hashtags like #elpasostrong and #boulderstrong are still used in reaction to these mass shootings but we see wider usage of other hashtags like #stopasianhate, or those related to gun reform. We also see this trend occurring in the earlier El Paso shooting, which reflected anti-immigrant sentiments emboldened by the previous administration, and also included hashtags such as #trump, #whitesupremacistterrorism, and #guncontrol now. Figure 4. Hashtags used in response to the 1 October shootingSource: Authors Figure 5. Hashtags used in response to the El Paso and Dayton shootingSource: Authors Figure 6. Hashtags used in response to the Atlanta and Boulder shootingsSource: Authors One of the difficulties in analyzing hashtags is that they often vary in the exact spelling or phrasing. We deal with this by putting the variations of an overall phrase into a hashtag bundle, as in Figure 7. These bundles include those that mention "prayfor" and is typically followed by a city name, "morethan" which is part of the full phrase "morethanthoughtsandprayers." The category of "gun" most often refers to "guncontrolnow," "gunreform," among others that appear in the word clouds. Finally, there is the variation of a "*cityname*strong." Since the 1 October shooting has more than three times the hashtag usage as both the Atlanta and Boulder shootings combined, we compare the relative usage of the hashtag bundles. El Paso data is excluded since the hashtag usage is not nearly as concentrated around such phrases. There is a major decrease in the share of hashtags praying for the victims, their families, or the community for recent mass shootings. Conversely, there is an increase in the sentiment that we need more than "thoughts and prayers." The same is true in the rallying effect that a mass shooting used to have, with a decrease in "*cityname*strong" in the Atlanta and Boulder shootings. Hashtag usage related to gun control and reform are quite similar across the shootings, even in the context of the more supportive nature of the 1 October responses. Figure 7. Relative popularity of hashtag bundles between the different shootings

Source: Authors While there are, of course, limitations to what we can infer from this data, it provides a glimpse of a more generalized shift in sentiment away from passive mourning to anger and desire for an active policy response. This is particularly the case when shootings are targeted toward a specific group, as in the case of politically motivated violence against Hispanics in the August 2019 El Paso shooting and Asian Americans in the case of Atlanta. We need to know much more about the social and emotional costs of this violence—not least as it seems to come in contagious waves across events that exacerbate an already gruesome death toll. This is particularly important at a time when gun violence-related events have increased by roughly 30 percent between 2019 and 2020, while opioid and other drug overdoses have almost doubled, in large part due to the toll of the COVID-19 shock on mental health (these numbers are from in-progress analysis of EMS first responder data by one of us—Graham—with Emily Dobson of the University of Maryland). At this juncture, though, it is our hope that even this limited assessment of those costs—and the increasing concerns about gun violence—can translate into support for policies to reduce it. While gun reforms have proven politically difficult to pass in the past, the new administration is at least providing an opening to do so. What is clear, though, is that the victims of this violence—and their grieving family members and friends and an increasingly tattered social fabric—deserve more than thoughts and prayers. Note on methodology Several data collections are utilized for this study that pertain to different mass shootings in the U.S., starting with a collection created by University of Nevada, Las Vegas Libraries in the week following the 1 October shooting in 2017 and contains more than 14 million tweets. We compiled three more collections, including one for the El Paso shooting in August 2019 with approximately 700,000 tweets that also contains reactions to the Dayton, Ohio shooting that occurred one day later. The other two collections refer to the Atlanta and Boulder shootings that occurred in March 2021. Since the Atlanta and Boulder shootings occurred within six days of each other, many of the tweets discussing the Boulder shooting often mention the Atlanta shooting and vice versa. These two collections where combined and duplicate tweets removed, resulting in over 2 million tweets collected from March 16-25. While Twitter data does not provide robust detail on the socioeconomic and demographic data, Twitter users, who comprise 22 percent of the American population, are typically younger, more educated, and wealthier than the general public. The tweets were catalogued using the open-source tool known as Twarc, which can archive tweets that pertain to a specific search term like "vegas," as an example. For the figures shown here, we focused on the hashtag and emoji usage, and extracted them from the "full text" of the tweets. The emojis were then converted from Unicode to their written-out names. A greater discussion on the methodology and drawbacks of Twitter data can be found in our blog "How misinformation spread on Twitter." This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| What will Facebook’s ban mean for Donald Trump’s future? Posted: 05 May 2021 11:09 AM PDT By Elaine Kamarck Today Facebook's Oversight Board, (its self-designated "supreme court") upheld the decision to ban Trump from its platform. His account was suspended the day after the January 6 insurrection for his role in promoting and condoning the violent attacks on the Capitol that resulted in 5 deaths, at least 138 injuries, destruction of property, and over 400 arrests so far. However, the board took issue with the indefinite nature of the ban. The ruling stated that Facebook itself should reevaluate the ban within 6 months of this decision. This is just the tip of the iceberg on the myriad legal and ethical issues coming up in the years ahead as we struggle to balance the power of private social media companies with the demands of free speech and the importance of the market place of ideas. In the meantime, the political question is what does this mean, if anything, for Donald Trump's future? For four years the press and the public reacted to an unprecedented barrage of Trump Facebook posts and tweets—sometimes appearing early in the morning or late at night. It wasn't too hard to distinguish between his own messaging and official messaging. His own was more outrageous, more prone to spelling errors and often at odds with what the rest of his government was saying. His musings appeared regularly on television news shows, often followed by administration officials trying gamely to figure out what he meant or how it wasn't really the opposite of what his government had just said. And then, because of decisions by Facebook and Twitter, he went dark only a few weeks before he left office for what has been a relatively quiet retirement at Mar a Lago. What impact did going dark have on his popularity? Following is a graph from RealClearPolitics that charts the average of Trump's approval ratings starting on January 6, the day of the insurrection at the Capitol, to the end of April. On the day of the insurrection Trump was viewed unfavorably by slightly more than half of the public and the gap between his unfavorable ratings and his favorable ratings was 10.5%. Ten days after the insurrection, as more and more people digested Trump's role in what happened that day, the gap between his unfavorable ratings and his favorable ratings grew to 21.6% of the public. But in the months following he gained back some of what he had lost and the gap has remained more or less stable—at about 16% as of the end of April.

So far three months of relative silence from Trump on social media do not seem to have affected his standing with hardcore supporters that appear to constitute between 35% and 41% of the electorate. These numbers are more or less the same as Trump's numbers throughout most of the second, third and fourth years of his presidency, which were notable for the fact that unlike previous presidents he never obtained favorable ratings from 50% of voters. The stability in Trump's numbers leads to a variety of hypotheses about the importance of social media. First, it is possible that Trump supporters, hostile to the media and big corporations, do not respond to survey research and thus support for Trump is lower in polls than it is in reality. This possibility is supported by the fact that turnout for Trump in the actual 2020 election was far greater than many polls had predicted. The second possibility is that the impact of social media on politics is not as influential as members of the political establishment and the press think it is. A Pew poll from this spring found that 70% of social media users "never or rarely post or share about political, social issues." In other words, a subsection of the population—probably the same people who, in a different generation would have been mailing letters or calling into radio shows—create a large portion of the social media noise. The third possibility is that by the time of his election loss Trump had created a hardcore base within the Republican Party that was powerful enough to dictate internal party decisions. Look, for instance, at the attempt to dislodge Trump critic Congresswoman Liz Cheney from her leadership position. That base may have solidified to the point where it does not need constant tending by Trump himself, thus making access to social media platforms less crucial. In spite of his being banned from social media his support among Republican voters has remained strong this year, as the following table using data from the Morning Consult/Politico poll indicates. Table 1: Donald Trump's favorability among Republican voters (Morning Consult/Politico)

This strength, however, may have come at a cost. While Trump appears to have solidified his hold over the Republican Party, he also appears to have damaged the brand. Gallup has asked about party identification in polls going back decades. By the end of the first quarter of 2021 they found that people who identify as Democrats were more numerous than people who identified as Republicans by a margin of 49% to 40%. This is the biggest gap in party identification in a decade. It also correlates with an increase in people who say they are independent. My final hypothesis is that even if Trump does return to social media, it is possible that his pronouncements will not be magnified by the mainstream press, especially television, now that he is no longer president. During his presidency Trump's most outrageous lies were covered because he was the president and many reporters and editors felt that they had an obligation to report what the president said. They may not feel the same obligation to an ex-president in Florida. (In the week after he was silenced, misinformation about the election dropped 73% according to a study by Zignal Labs.) This possibility has, no doubt, been a concern to Trump who just recently launched a new site "From the Desk of Donald J. Trump" as a way of getting around the social media ban. So while today's decision has momentous consequences for social media in the coming decade, it may not have momentous consequences for Donald Trump's future. He remains the undisputed leader of a political party but that party has lost two elections in a row (2018 and 2020). In four years as president of the United States he was unable to expand his base. And now, the changing demographics of the country seem to be working against him. With or without social media he may have trouble expanding his following enough to become president again. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Posted: 05 May 2021 08:18 AM PDT By Matthew Collin The global financial system is infected with dirty money. Despite decades of progress in strengthening policies aimed at stamping out cross-border tax evasion and money laundering, many of those looking to stash their money overseas to avoid taxation or prosecution can still do so with relative impunity. As the FinCEN Files scandal last year revealed, banks—themselves the tip of the spear in the fight against financial crime—often fail to catch the worst offenders in a timely manner. Tax authorities and financial intelligence units also struggle to keep up, due to the basic fact that it becomes very difficult to track what happens to money the minute it leaves your economy and goes offshore. A lot of hidden wealth either ends up in or transits through tax havens: jurisdictions that offer low tax rates and high degrees of financial secrecy, including legal systems and regulations that make it easier for people to keep their wealth hidden from the prying eyes of their governments back home. In the past decade many governments have made a lot of progress in getting archetypal havens to start sharing information on the owners of offshore wealth. But while these efforts have succeeded in sending a lot of tax haven clients scrambling for new places to hide their money, they have given policymakers and researchers only a glimpse into who uses and benefits from tax havens.

Occasionally, data leaks mean we get to fully rip back the curtain surrounding the offshore economy. In late 2019, Distributed Denial of Secrets, a Wikileaks-style journalist collective, released a leaked cache of internal files and emails from the Cayman National Bank and Trust — a bank based in the Isle of Man, home of a large offshore financial industry. The leak appears to have been perpetrated by the anonymous hacktivist known as Phineas Fisher. The hacker—whose only live interview to date is in the form of a sock puppet—made their name by hacking surveillance and spyware organizations like the Gamma Group and Hacking Team. Thanks to the leak, investigative journalists around the world have highlighted several of the bank's more questionable clients. These ranged from a Russian billionaire on the lam from the IRS for tax evasion, a former Armenian government official under investigation for corruption, and even companies connected to the German payments company Wirecard, which recently collapsed under the weight of a 1.9 billion euro accounting fraud scandal. But while the headline-grabbing cases are more salient, they don't tell the whole story. In a new working paper, I use the data from the leak to start answering some fundamental questions about who stores their money in tax havens and how that should alter our approach to fighting dirty money, both abroad and at home. After a year of going through the data, which at its peak covered about $200 million in offshore deposits, I made three discoveries. Discovery #1: The rich will always be with us, but audit rates need to reflect thatThe data in the leak allowed me to pinpoint where the bank's clients were based: both those with their own account and those indirectly connected to the bank because they owned or benefited from an entity that held an account there. This made it possible to understand whether clients were more likely to come from richer parts of the world and if the amount of wealth they had—measured by their account balances—suggested they were likely to be rich themselves. Clients of offshore banks appear to be wealthy by nearly any metric. Adjusted for each country's population, there are nearly five times as many clients from countries with a GDP per capita of $50,000, such as Sweden, than there are for those with a GDP per capita of $5,000, such as Ghana. No matter what country they were based in, at their peak the amount of money clients had in their bank account was substantial, with the median person having about twice their national income. For some countries, the difference was even more stark: Clients from Ukraine had roughly 50 times their national income in offshore deposits and those from Nigeria had roughly 150 times. Even when we look within a country, offshore clients appear rich. Pinpointing where the bank's British clients lived revealed that they were more likely to be based in parts of the United Kingdom that were richer and had higher property values. While "rich people like to use tax havens" is not going to make the headlines, it reinforces a growing body of evidence that, no matter which country you are looking at, it is those that are the most well off that are the most likely to stash their money in offshore accounts. This wouldn't be a problem if tax authorities knew where to find that money, but they don't. A recent working paper written by academics in collaboration with the IRS shows that random audits routinely fail to capture the extent to which richer taxpayers stash their wealth abroad—leaving approximately $15 billion in taxes on the table (most of which was owed by the top 0.1 percent of the income distribution). This not only makes it hard to raise revenue, it forces tax authorities to claw back more money from poorer people by auditing them more often. The offshore world doesn't just enable the rich to reduce their tax bill, it amplifies inequality around the world. To fight back, tax authorities are going to have to start investing in auditing rich people more—a reality that the Biden administration has recently embraced by proposing an $80 billion increase in IRS funding. But to set those audits up for success, we have to break down the information barriers that governments face. This means expanding and improving upon the growing global network of exchange agreements that tax authorities use to hunt down those offshore deposits—an effort that will require not only more coordination, but full participation from the United States. Discovery #2: Many offshore clients have connections to people with political powerFar too often, politicians use their connections to enrich themselves, their friends, or their families. Because of this, banks are required by most regulators to identify clients who wield political power—or those close to powerful people—to ensure they are not using the financial system to hide ill-gotten gains. The data from the leak indicate that Cayman National Bank did just this: Records suggest they maintained a register of these politically-exposed persons (PEPs), conducted frequent due diligence, and reported them to the authorities whenever concerns arose. Yet despite being watched more closely, offshore clients with political connections displayed some worrying characteristics. Compared to other clients of the bank they were more likely to use tax havens both as a domicile and as a source of funds. They also controlled substantially more wealth during their relationship with the bank. Relative to the number of ordinary clients the bank was connected to, PEPs were also disproportionately from countries that have a poor record on corruption, many of them from post-Soviet countries. None of these statistics prove anyone was doing anything wrong, but the presence of a large number of politically connected clients in the offshore (or any other) economy should give regulators pause. Because a government official working in a financial intelligence unit will only observe a politically-connected client if and when a bank registers a concern (through a process known as suspicious activity reporting), the presence of political elites in the banking system will largely go unseen by regulators. Regulators need to know when their economies are being targeted by those with political power—either those at home or from abroad. For example, while the presence of a single Russian politically connected client wouldn't be cause for alarm—regulators would certainly want to know if most of a bank's clientele were Russian PEPs. One solution would be to require banks to begin reporting aggregate figures on PEP clients. This could be an important component in the risk assessments that governments around the world routinely conduct in order to understand where the money laundering threats and vulnerabilities in their economy lay. Discovery #3: Shell companies are hurting our ability to understand how much wealth sits offshoreMost people with offshore bank accounts don't hold money under their own name, but instead establish shell companies—firms that have no physical presence and don't engage in any real forms of economic activity—to hold it on their behalf. Their presence can make it very hard for regulators (and even banks) to fully understand who ultimately controls a bank account or benefits from a transaction. Even when shell companies in tax havens are being used for legitimate reasons, their existence creates a fundamental problem for the way we measure offshore wealth—one that international tax researchers have been grappling with for years. Most studies of offshore wealth and its drivers rely in part on data from the Bank of International Settlements (BIS). Every quarter, banks in participating jurisdictions are required to count up and report all the deposits owned by foreigners (known as cross-border liabilities), which the BIS then aggregates and publishes as part of its Locational Banking Statistics. However, the BIS only requires banks to report this information based on the residence of "immediate counterparty"—that is, the most proximate owner of the offshore wealth. When that is a person, it is a relatively straightforward process: Deposits owned by French residents will get assigned to France. But when a French resident owns those deposits through a shell company based in Liechtenstein, the bank will only report that they are controlled by someone in the latter, not the former. In practice, this means that the BIS's data—without adjustment—will undercount wealth held in tax havens by the rest of the world. How badly does this skew the data? Information from the leak offers a few clues: Because it is possible to observe the ultimate "beneficial owner" or "beneficiary" of the offshore entities that had an account with the bank, it's possible to calculate the share of deposits that are actually owned by foreigners who are based in non-haven countries but are instead reported to the BIS as being owned by people in tax havens because they are owned through entities based in havens. Once this correction is made, the differences are stark: About half of all wealth owned by people who don't live in tax havens is incorrectly reported as being owned by people who live in tax havens (for the record, very few people live in tax havens). The presence of shell companies and the way data on them is collected makes it harder to understand how much wealth sits offshore, but much of this can be fixed with a simple tweak of the rules. The Bank of International Settlements should ask banks to start collecting information based on the ultimate residence or nationality of their clients. This would not be an onerous exercise for banks, as they are already required to collect this information as part of their due diligence obligations for onboarding new clients. It would also be in keeping with the BIS's efforts to understand the ultimate nationality of ownership for other financial instruments, such as debt securities. Turning the tide on illicit wealthMuch like the lessons learned after the Panama Papers scandal or the FinCEN Files, these three discoveries were only possible because someone leaked data onto the internet. While we should take every opportunity we can to learn from these leaks, it's not a sustainable way to bring light to the darkest recesses of the offshore world. Fighting dirty money is going to require a concerted effort by regulators, law enforcement, the press, civil society, and researchers around the world. The closest thing to a silver bullet that the effort needs is better information on who owns what. And we can get that information by passing laws that force the ultimate owners of shell companies and trusts to reveal themselves. At least 80 countries around the world have started making progress on this front, passing laws to create what are called "beneficial ownership" registries. The U.S. has recently followed suit with the introduction of the Corporate Transparency Act, which will require companies to disclose this information to FinCEN, our financial intelligence unit. But while providing that information to the right people in government is a first step, it isn't enough. When possible, data from beneficial ownership registries (and even anonymized information from tax exchange agreements) needs to be made public. This enables the public to act as an auditor as a last resort: Civil society and the media have highlighted major issues in beneficial ownership registries in both the U.K. and Luxembourg. It also helps entrepreneurial data sleuths hunt for clues that law enforcement might miss. Our ability to understand and curb the impact that offshore wealth has on our world shouldn't be decided by the efforts of hackers and investigative journalists. We need policies in place to make this kind of data more freely available, to everyone. While the financial system may be infected with dirty money, it turns out that sunlight can be a powerful disinfectant. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Figures of the week: Africa’s renewable energy potential Posted: 05 May 2021 07:18 AM PDT By Leo Holtz, Christina Golubski In a recent article from the International Monetary Fund's quarterly publication Finance and Development, researchers explore how scientific advances in renewable energy technology, its falling costs, and the continent's geography can contribute to renewable energy becoming a prominent, affordable, and competitive source of electricity in Africa. Indeed, while access to electricity in sub-Saharan Africa is expanding, with the region's population expected to double from 1 billion people in 2018 to over 2 billion in 2050, researchers with the IMF forecast that demand for electricity will increase 3 percent annually. Right now, the main sources for the region's energy—coal, oil, and traditional biomass (wood, charcoal, and dry dung)—are associated with severe environmental and health damage. Integrating and designing an energy mix largely reliant on renewable energy would, according to the authors, simultaneously support strong growth, low emissions, and ecologically sustainable development. However, as the authors illustrate in Figure 1, Africa's current energy mix is almost entirely composed of fossil fuels and biomass. Figure 1. Africa's energy mix: Present and projectedSource: Gregor Schwerhoff and Mouhamadou Sy, "Where the Sun Shines," Finance and Development, IMF, 2020. Although the authors address the applicability of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies accompanying high emissions fossil fuel and biomass energy production in the future, they are uncertain about large-scale reliance on these accompanying technologies due to lack of testing at industrial scale. Importantly, the authors' projections of the continent's energy mix illustrates that fossil fuels and biomass will play an increasingly important role by 2050, but, ultimately, both conventional energy sources will decline and be dwarfed by a diverse array of renewable energy sources dominated by solar. The authors also write that a substantial reduction in renewable energy's costs will enable Africa's renewable energy transformation. Figure 2 illustrates the evolving cost of various forms of renewable energy. The most dramatic change is the precipitous decline in the cost of solar photovoltaic energy, which decreased 77 percent from 2010 to 2018. Trailing solar's improvement in affordability, are both on- and off-shore wind, which experienced notable, yet less sharp, declines in cost. Figure 2. Cost of generating electricity with renewable sourcesSource: Gregor Schwerhoff and Mouhamadou Sy, "Where the Sun Shines," Finance and Development, IMF, 2020. However, while wind and solar have become increasingly cost-competitive, the implementation of renewable energy in Africa continues to lag behind much of the rest of the world: Solar and wind together constituted 3 percent of Africa's generated electricity in 2018, versus 7 percent in other regions of the world. Given that technological advances in energy storage have mitigated supply fluctuation issues with renewable energy and, thus, bolstered its reliability, the authors suggest financing renewable energy in Africa is now the most significant challenge. They contrast the comparatively inexpensive cost of building a new fossil fuel plant, which is expensive to run, and the high installation costs of renewable sources, which are inexpensive to operate. The high upfront cost of renewable energy necessitates greater capital expenditure. Consequently, the authors propose that African countries "mobilize public, private, and multilateral and bilateral donor financing to raise funds" for renewable energy infrastructure projects to mitigate the expensive upfront costs. In addition, they also encourage advanced economies to honor the 2015 Paris Agreement—in which those advanced economies committed to "0.12 percent of the world's GDP a year through 2025 to address the needs of developing economies" —as a means to finance renewable energy infrastructure development and facilitate the transition to a low-carbon energy economy in Africa. For more on climate change and Africa, read "Climate adaptation and the great reset for Africa" and "Africa can play a leading role in the fight against climate change." For more on renewable energy and Africa, read "The effects of the global energy transition in Africa: Disruption and opportunity" and "Figures of the week: Access to affordable, sustainable, and modern energy in Africa." This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| How tax incentives can power more equitable, inclusive growth Posted: 05 May 2021 06:31 AM PDT By Lourdes Germán, Joseph Parilla For decades, tax incentives have been a major policy tool to spur economic development and attract and retain good jobs. In recent years, however, these incentives have come under heightened scrutiny from the public, with growing concerns over lost tax revenue and localities' fiscal health. But tax incentives can influence economic growth and opportunity in cities if they are strategically targeted to the right businesses and business behaviors. With the COVID-19 pandemic triggering budget crises for municipal governments, there is even greater need for them to wield incentives effectively in ways that support inclusive growth, racial equity goals, and fiscal health. The good news is that cities are experimenting with new evaluative tools and practices that help maximize economic, fiscal, and social benefits. When used together, two of these tools—inclusive incentive scorecards and equity indicators—can allow cities to prioritize areas of high need, understand existing inequities, and ultimately gear tax policies to incentivize specific strategic goals. An underlying premise of these tools is that when a city tracks and measures specific business behaviors and inequities, it will be better able to define clear tax incentive policy goals from the start. And over time, that city will be better equipped to judge whether certain policy choices are enabling them to meet fiscal health, equity, and inclusive growth goals. Using inclusive incentive scorecards to target inclusive growthIn our view, the broad goal of economic development should be to put a local economy on a trajectory of higher growth by increasing the productivity of businesses and workers in ways that raise everyone's living standards. But in the period of historic economic expansion preceding the pandemic, growth was not shared evenly. The prevailing model of tax incentives has been to reward a narrow set of business behaviors—namely, the creation of new jobs, the retention of jobs under threat, and the creation of construction jobs. (Other important factors such as wage levels, local hiring, and affordability requirements for housing projects have only entered incentive formulas in recent years.) Recent research by one of us examining economic development incentives in four U.S. cities found that incentives were aligned with some, but not all, of four important inclusive growth principles:

An inclusive incentives scorecard can help cities better align economic development policies to drive inclusive growth. This tool—developed by Brookings authors with influence from economic development leaders in Indianapolis, Portland, Ore., and Syracuse, N.Y.—helps decisionmakers better target incentives to generate inclusive growth by focusing on four areas of business behaviors:

City officials can use the scorecard to look at various employer characteristics and behaviors falling into these four areas, and then rank them across two dimensions: impact and implementation. The impact score captures how much certain behaviors will contribute to inclusive growth. The implementation score captures whether city governments and local partners can track or support a specific business behavior.

Ideally, cities incentivize business behaviors that can be mapped in the upper right quadrant—meaning they are both impactful and implementable. While the scorecard needs to offer a widely relevant baseline of employer behaviors and characteristics, it can and should be tailored to a city's local economic and institutional circumstances. The scorecard in action: IndianapolisA handful of cities have used the inclusive incentive scorecard to target tax incentives in ways that support more equitable, inclusive growth. The city of Indianapolis' efforts to drive such growth through tax incentives have focused on "opportunity industries." These industries in Central Indiana can both grow the economy and create good jobs that don't require a bachelor's degree, said Mackenzie Higgins, a policy advisor to the city's mayor. According to Higgins, a first crucial step toward adjusting Indianapolis' incentive policies was aligning the city's leaders and economic development team (which handles transactions) on broad goals and how to quantify success. They set collective policy priorities, including: growing the economy, assisting distressed geographies, and improving access to jobs through training, transit, and child care. Then the city created a scorecard to evaluate the value of economic development projects. It set a family-sustaining wage baseline for scoring purposes: Only jobs paying at least $18 per hour with health care benefits would be considered in the scorecard. The scorecard, which supports tax abatement policymaking, evaluated criteria that included job creation, job location, and the company's industry. Indianapolis also requires companies to invest 5% of their tax savings into either transit, workforce training, or child care support for employees. "Those were three elements identified in our community as barriers to employment," Higgins said. In terms of removing those barriers through targeted incentives, Higgins flagged a major lesson learned that city leaders should keep in mind. "Ensuring that we have the appropriate ecosystem of partners to help facilitate training, transit, and child care investments was crucial," she said. For example, if a company wants to allocate its 5% of savings to workforce training, the city connects the company to a specialized training provider to help grow talent. "That type of partnership has been fundamental to being able to implement this approach on the ground," Higgins noted. Improving fiscal health through smarter tax incentivesAlong with supporting inclusive growth, economic development incentives can enhance the ability of local governments to plan, manage, and pay for critical public services and investments. For example, Providence, R.I. structured property tax stabilization agreements with businesses in a way that contributed to the city's broader efforts to strengthen its fiscal health. "We've used the agreements to expand the city's tax rolls by incentivizing new development, not just downtown but in the neighborhoods as well," said Lawrence Mancini, Providence's chief financial officer. "It's allowed us to stabilize and expand the city's tax roll. We've gone seven years without a tax rate change." Incentives structured with targeted attention to fiscal health can also boost the level of funding for capital expenditures. This increased funding can provide valuable multiyear resources for critical infrastructure, helping to ease a long-term budgetary stressor many localities face. Growth of "own-source revenues" is another potential fiscal health benefit. It is well documented that when incentives are structured to enable a locality to capture partial or full property taxes from firms that would have otherwise located elsewhere, this important category of revenues can grow. Expanding own-source tax revenues is integral for resource-constrained jurisdictions; tax incentives structured for a multiyear period can deliver especially meaningful results. In order to fully track the fiscal health impacts of economic incentives, localities should adopt a robust Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) 77 measurement framework in their financial statements. Mapping cities' equity landscape with equity indicatorsAs cities look to evolve incentive policies in ways that spur more equitable economic development, a common challenge is uncertainty about needs and trends. Without data establishing a baseline understanding of a city's unique equity landscape, thinking about which outcomes that incentives should focus on is difficult. This is complex terrain—and equity indicators can help map it. This flexible tool, developed by the City University of New York's Institute for State and Local Governance in partnership with New York City, measures a city's current state of equity and how it changes over time across multiple domains and groups. Equity indicators help cities do three things:

Drawing on public data from federal and local sources as well as administrative data from local agencies and organizations, cities across the country have developed custom equity indicators tailored to their specific priorities. Pittsburgh, for example, zeroed in on education, workforce development, and entrepreneurship, among other areas. As shown in the below graphic, city officials tracked multiple indicators within each area.

Using this granular data that reveals areas of great inequity, a city's economic development team can proactively tie incentive policies to urgent needs. When companies knock on the city's door asking for tax incentives, officials can respond using a data-driven strategic framework that puts money to work where it's most needed. "Through the use of equity indicators, we were able to implement a data-informed process," said Majestic Lane, chief equity officer and deputy chief of staff for the mayor of Pittsburgh. One way the city used indicators was to address particular neighborhoods' challenges. For example, high housing needs were identified in the predominantly African American Hill District, so a portion of tax abatements related to a project there were required to be used in that community. "The data gave us a more scalpel approach to see what's the biggest equity issue in a particular neighborhood," Lane said. Developing and implementing new data-driven tools and practices takes time and effort. But the implications are significant. Tax incentive policies and programs can be better designed around equity-based goals and inform fiscal choices. Businesses can be held accountable for specific targets that meaningfully change their investments. That, in turn, increases the likelihood that incentives spark economic development that would not otherwise have occurred—inclusive growth that enhances both cities' fiscal health and equity outcomes. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

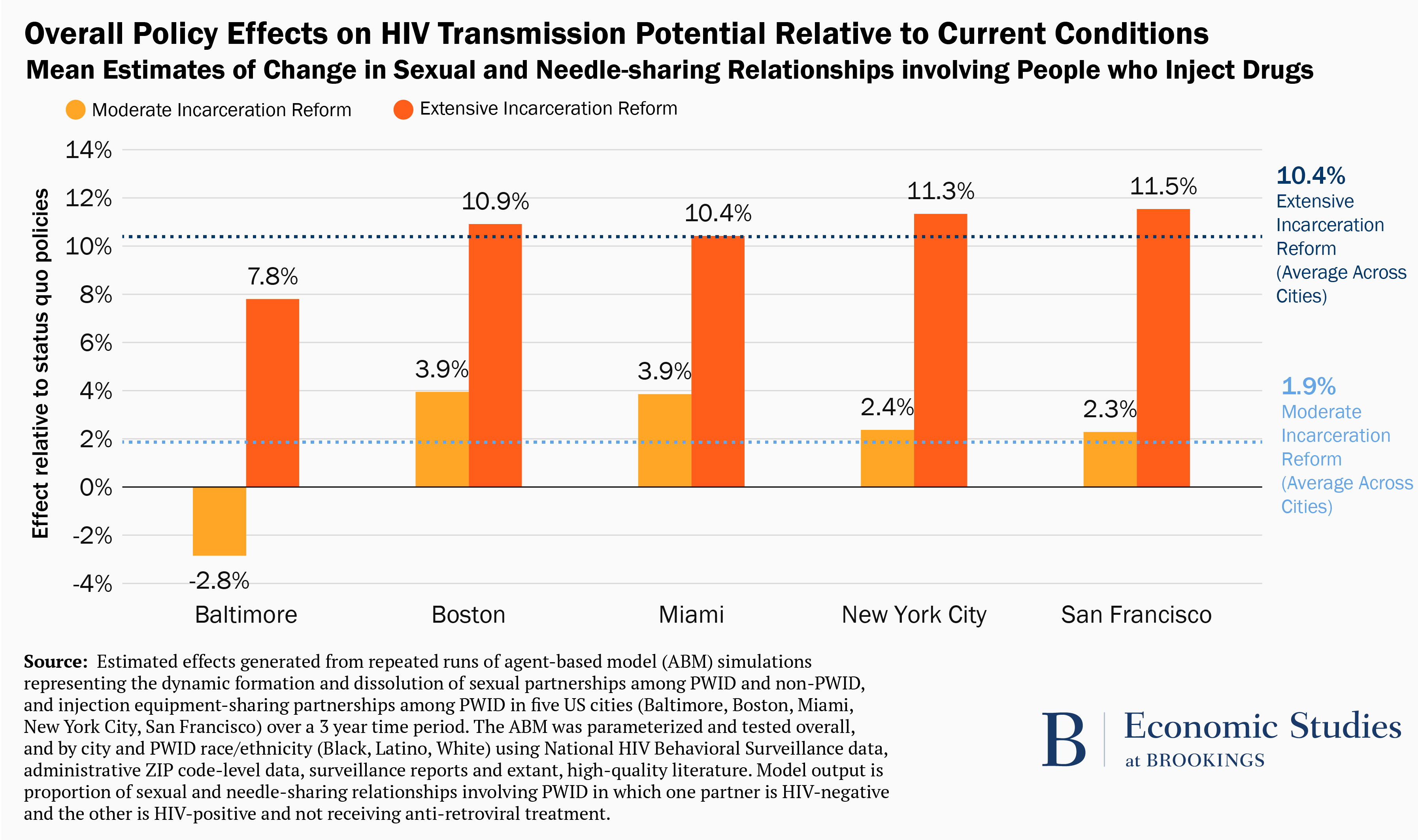

| Linking criminal justice reform and health policy: Incarceration rates and HIV prevalence Posted: 05 May 2021 06:02 AM PDT By Matt Kasman The opioid epidemic, ongoing since the 1990s and increasingly deadly during the COVID-19 pandemic, is linked to another long-standing and hard-fought public health crisis: HIV. People who inject drugs (PWID) experience elevated rates of HIV acquisition and transmission, a tendency that has been exacerbated by the opioid epidemic. Because this group is a potent vector through which HIV remains active in our society, changes in policies that affect PWID can have broader public health ramifications. In a new study published in the International Journal of Drug Policy, researchers found that without careful and deliberate mitigation efforts in place, criminal justice reforms that result in large, rapid decreases in incarceration rates can lead to an increased risk of HIV spread through communities. To identify this unintended hazard, authors of the paper had to overcome substantial research challenges: collecting data on PWID is difficult, and there are multiple overlapping sources of influence through which policy might affect HIV transmission. The Brookings Institution's Center on Social Dynamics and Policy worked with colleagues across several institutions to create a sophisticated computational simulation tool that can provide insight into potential policy effects. Recently published research includes a description of this tool along with findings from our application of it to multiple types of relevant policies. In each of the five metropolitan areas considered, simulations indicate that criminal justice reform policies that result in extensive reductions in incarceration rates increase relationships involving PWID that have the potential for HIV transmission (figure 1). On average, there is an approximately 10% increase in incidences of such relationships compared to simulation runs in which incarceration rates remained at current levels. There are only small changes (mostly slight increases, although we estimate a slight decrease in Baltimore) in these relationships associated with criminal justice reform policies that result in moderate decreases in incarceration rates.

These overall metropolitan area impact estimates can mask some potentially important variation in who is affected. Figure 2 disaggregates the effects of extensive incarceration rate reduction on relationships with the potential for HIV transmission by race in three metropolitan areas. The patterns depicted differ across each of these contexts, with white individuals experiencing the greatest increase in San Francisco and Black individuals in Miami and New York City.

Criminal justice reform initiatives are rooted in efforts to advance social justice and meaningfully enhance racial and ethnic equity. In general, these goals are well-aligned with public health. Thus, the potential for increased spread of HIV resulting from reductions in incarceration rates is counterintuitive. However, this finding should be taken with two important caveats in mind. The first is that the simulated policy effects are restricted to a relatively short time horizon of three years. Potential positive effects of incarceration reform including decreases in HIV risk behaviors, stabilization of sexual networks, increased access to drug treatment, and HIV care and treatment might eventually offset any initial uptick in community-level HIV prevalence that follows criminal justice reforms. Second, these simulated effects are absent any concerted efforts to mitigate them. Prior research suggests that ensuring HIV prevention and treatment among justice-involved populations and the persons with whom they interact in the community requires a multipronged approach that accomplishes the following: (1) bridges gaps between HIV and behavioral health services in correctional settings and those in the community, (2) engages formerly incarcerated men and women into HIV testing and treatment, and behavioral health programs in the community, (3) builds trust in the medical system and autonomy among formerly incarcerated men and women, (4) facilitates community reintegration by reducing barriers to employment, housing, and social benefits, leveraging social capital, and (5) integrates case management and patient navigation in post-release and reentry programs. Many of these approaches are documented to have strengthened reintegration and to have increased HIV care engagement and retention. That is, policymakers can proactively and strategically engage in efforts that buffer against unintended, negative consequences of criminal justice reform. When attempting to limit or prevent increases in HIV prevalence stemming from criminal justice reform, policymakers should keep in mind that "one size does not fit all." In our simulations, effects of reductions in incarceration rates vary across geographic settings and, within them, across racial and ethnic groups. Therefore, consideration of underlying contextual factors should play a key role in crafting public health strategies that accompany criminal justice reform. Beyond the immediate implications for criminal justice reform, this work is a good example of the importance of exploring interactions between policy domains rather than only looking at them in isolation. The relationships between areas like health and criminal justice, as well as education, labor, and others, are important and understudied—and often wholly overlooked – to the detriment of policies they govern and people they affect. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Mothers are being left behind in the economic recovery from COVID-19. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

No comments:

Post a Comment